Mr. Mac and The Bushytail Gang: A Squirrel-Dog Revival in South Carolina

Once upon a time, squirrel dogs were as common in the South and Midwest as cotton gins and working mules. These small-to-middling-size breeds–mountain curs, treeing feists, Kenner curs, treeing brindles, and the like–were a family staple with pioneer roots. “When our early settlers came into this country,” English tells me, “they brought these little dogs with them and they hunted everything. They’d tree a coon or a squirrel, run a deer, run a hog. You couldn’t get by without them.” Such breeds are a part of American sporting literature as well. George Washington wrote about yellow cur dogs. Abraham Lincoln was a fan; a “short-legged fice” was hot in pursuit of bruin in his poem “The Bear Hunt.” These treeing dogs figured in William Faulkner’s “The Bear” and Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings’s The Yearling, and the dog that played Old Yeller in the movie, many say, was a black mouth cur. By the middle of the 20th century, however, most of these specialty hunters had nearly disappeared, and with them a small-game tradition with a storied past.

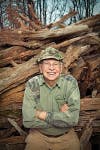

Squirrel hunting with dogs barely resembles my boyhood passion of hunkering down under a huge oak and waiting for targets to appear. It’s fast-paced and active, but something else is at work to bolster the future for these dogs, and that’s the fact that squirrel dogs and squirrel-dog hunting are particularly suited to the exigencies of modern life. Compared with many hound breeds, a 20-pound feist is more family-friendly and easier to keep in the house. Some states are lengthening their squirrel seasons to attract more hunters, so opportunities to chase bushytails are now available from summer through the end of winter. And part of the growth in squirrel hunting with dogs is coming from the ranks of coon hunters weary of late-night races and rabbit hunters struggling to find good hunting grounds. As a kid English hunted squirrels the way everyone else hunted squirrels. “Until I was 8 or 9,” he says, “I loved to sneak into some hickory trees before daylight. Back then, everybody still-hunted and we all used shotguns. I didn’t know what a .22 rifle was.” Then, in 1950, English went hunting with his “first known squirrel dog,” and he’s never looked back. He founded the South Carolina Squirrel Hunters Association, whose Whitmire, S.C., headquarters hosts the squirrel hunting world championship, and he’s single-handedly nurtured a squirrel-dogging craze that has helped reshape hunting in the region. These days, there are upwards of 30 hunters with squirrel dogs within a 15-mile radius of Whitmire, and almost without exception there is a connection to English. “He has people he’s never even heard of calling him on a weekly basis,” Chad English says. “People in the Wal-Mart stop him in the aisles. ‘Are you Mac English? I saw you on the Internet.’ We tease him about being a celebrity, but he’s not doing it for the attention. He’s just doing what he’s always done, and he loves to show other people what he loves. And it just seems like it’s caught fire.”

At the base of a soaring shagbark hickory, Jack, Buckshot, and a yellow cur named Ann are putting up a fuss. Unlike coon dogs, most squirrel dogs are silent on the track. Their job is to find a hot scent trail, narrow it down to the last tree climbed by their quarry, then pin the squirrel to the branches by raising a ruckus that keeps the animal’s focus off the hunters below. Now the dogs have their heads back and tails wagging, barking to beat the band, clawing at the tree, then backing off to watch the topmost branches in case the object of their desire starts “topping out” or “timbering,” jumping from tree to tree in an attempt to find safe haven. If dogs can smile, these three are. I am, too. After all, four grown men, two kids, three dogs, five guns, and thousands of dollars’ worth of high-tech optics and GPS dog collars surround a squirrel in a tree–or at least, a tree that may hold a squirrel. Much of the intrigue of squirrel hunting with dogs, I’m learning, is the challenge of actually trying to spot a squirrel whose life depends on staying hidden. These little jokers are wizards at disappearing in plain view. To find them, you never look for the squirrel itself. You look for a little piece of swollen limb, the dark spot of an eye, a piece of bark that looks slightly unbarkish, a lump on a branch, the sharp point of a squirrel’s ear sticking out from a piece of moss. And all of this is at 80 feet high or better. But this time, thank my lucky stars, the squirrel is stretched out on a sunny branch like a college kid at Daytona Beach. Not that it’s easy. I’d been warned to bring my best game to South Carolina. “That man can read a squirrel dog in the woods like nobody I’ve ever seen,” says Tree Time Kennels owner Russ Cassell, whose original mountain cur, Culbertson’s Wild Rose, is a world champion squirrel dog. “It’s uncanny to watch, like he knows everything they’re thinking.”

Training a squirrel dog is as simple a thing as you can imagine, according to English. As long as you start off with a squirrel dog. “About the only thing you can do is get a squirrel dog that comes from squirrel dogs, and get that puppy in the woods,” he says. “If squirrel hunting’s in him, it’ll come out. And if it ain’t, well, you got a long road ahead.” There are ways to tip the odds in a hunter’s favor. Many tie a squirrel tail to the end of a cane pole and run it up, down, and around the base of a big tree, with the puppy in hot pursuit. Others live-trap a squirrel and place the trap and squirrel on the ground and open the door in front of the puppy. “That young dog sees that squirrel going up a tree,” English says, “and most times, that will do the trick.” The end result is to get a dog “just pure eat up with squirrel,” English says, and watching what happens then is the great delight of squirrel-dog hunting. Early the next morning, we’re hunting a big swath of Sumter National Forest–open bottoms along timbered creeks thick with vines and scattered pines in the hardwoods. I lean against a big beech tree, its late-winter leaves still hanging on, and watch Buckshot work the woods. He’s a 30-pound shorthair vacuum cleaner, muzzle to the ground, sucking up scent. Buckshot runs around a tree (sniff-sniff), hops on a fallen log like a chipmunk (sniff-sniff), docked tail wagging. He inspects a tree stump (sniff-sniff), then a rock pile (sniff-sniff). He worms through a copse of cedars (sniff-sniff) anywhere a squirrel might run. Now he’s off wide open through the woods, nose stuck to the ground, around a white oak (sniff-sniff), then a red oak (sniff-sniff). Something catches his attention, and Buckshot is on his hind legs, paws on the oak trunk, dancing halfway around the tree (sniff-sniff) but whatever it is isn’t quite enough because suddenly he’s off again, disappearing into the woods.

“Naw. Can you?”

“Uh-uh.” “Is that him? See where the tree forks and forks again? Go up the right fork to where that piece of moss is on the trunk. I think I see a little piece of leg right there.” Yes, it is. We all jockey for position. There’s only one shot, though, a tight angle to the squirrel’s head, flattened against the trunk. And there’s not a tree positioned correctly for a rest. Which means it’s up to English. Years ago, he and his brother perfected a shooting position, tailored to the demands of a high-angle shot with no rest and no margin for error. Within seconds the man who’s nearly 80 years old is on the ground, legs interlocked like a pretzel, gun barrel at a 45-degree angle. This time, it’s me who fights a smirk. There is complete pandemonium at the tree–three dogs leaping and barking and clawing, and four hunters looking up in the branches with hands stuck in their pockets–and the old man balls up on the ground. Crack! My mouth drops open as quickly as the squirrel drops from the tree. That shooting lane couldn’t have been half an inch in diameter, a pinprick of clear sailing between vines and twigs and branches, maybe 170 feet to the target. I look down at English, and he hasn’t moved a muscle. Now he’s smiling at me. “I do believe,” English says, “that squirrel has a headache.”