The Five-Year Lion Hunt

A vintage tale that's part adventure story, part conservation report—and all about the mysterious big cats of the American West

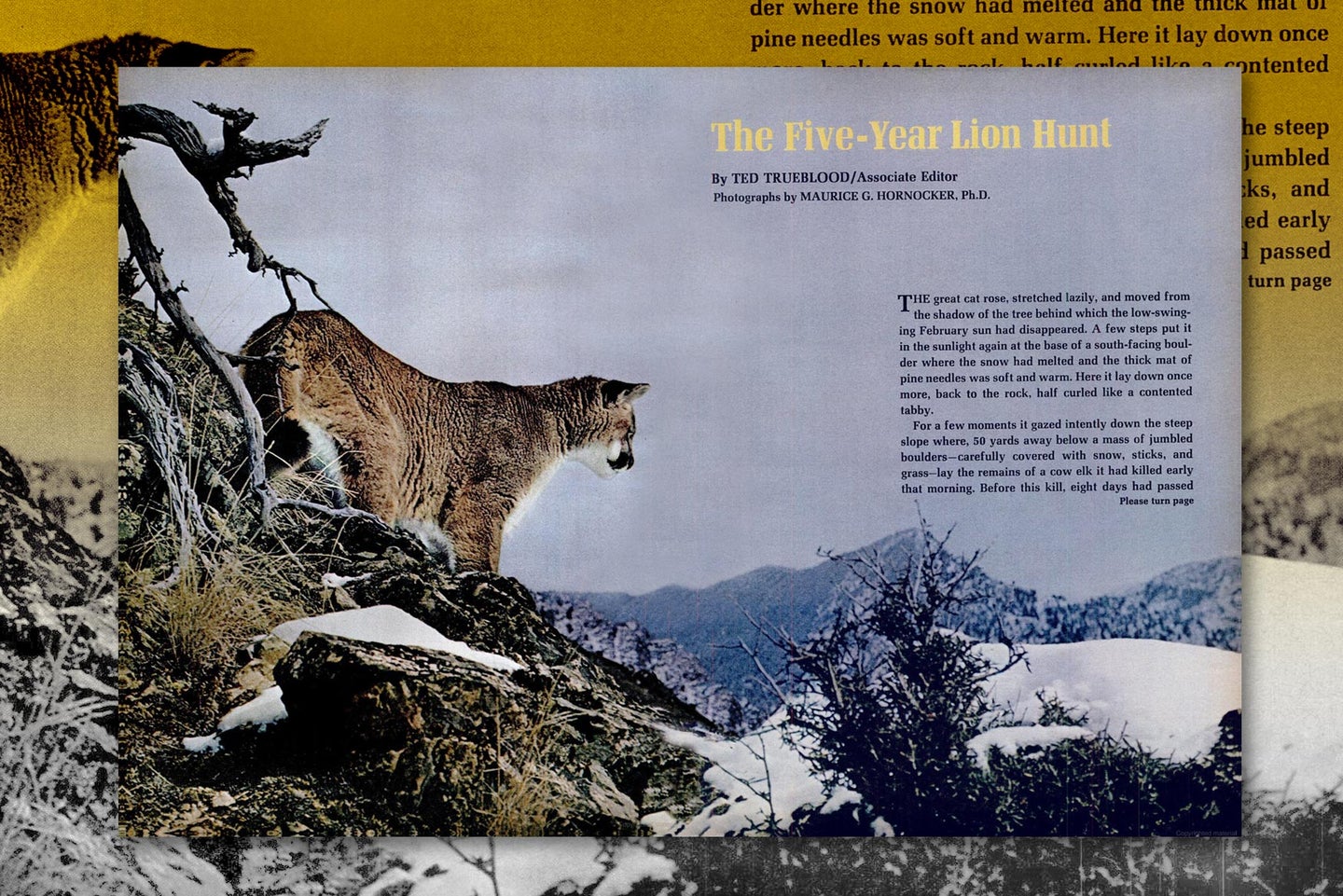

THE GREAT CAT ROSE, stretched lazily, and moved from the shadow of the tree behind which the low-swinging February sun had disappeared. A few steps put it in the sunlight again at the base of a south-facing boulder where the snow had melted and the thick mat of pine needles was soft and warm. Here it lay down once more, back to the rock, half curled like a contented tabby.

For a few moments it gazed intently down the steep slope where, 50 yards away below a mass of jumbled boulders—carefully covered with snow, sticks, and grass—lay the remains of a cow elk it had killed early that morning. Before this kill, eight days had passed since the cougar had fed. It had made several stalks, but in each case had failed to complete them. Cougar, unlike wolves, can’t outrun their prey. A cougar must get close, behind cover, and then—after a short, fast rush—leap on the startled animal.

The cat was a big male. It would weigh close to 160 pounds and stand 30 inches tall at the shoulders. It was more than 7 1/2 feet long including its 28-inch, black-tipped tail. Its predominate color was rusty brown, shading to a hint of black along its back and fading to white on its belly. Its head, broad and short like that of any cat, would have measured 6 inches across the top between the alert, upright ears, 8 inches from nose to back. There was some black near the muzzle, with a tuft of 5-inch whiskers on each side. Its big, soft-looking, furry feet would leave tracks 5 inches across in new snow. Its keen eyes were yellow, with round pupils.

Late the night before, driven by hunger, the big cat had come down off the rocky bluffs where he had for two days attempted unsuccessfully to stalk a band of bighorn sheep. The sheep seemed always to have an alert sentry watching and he had been unable to get close. He had swung down into the tangled Rush Creek bottom where the snow was 3 feet deep, climbed up through the Douglas fir on a north hillside, crossed a ridge, and started around this sparsely timbered south slope.

Then, far below, he saw the elk. Several cows and calves, clearly visible in the bright moonlight, were browsing the mountain mahogany that clustered on the rocky outcroppings, the bitterbrush that grew in the open areas, and occasionally cropping a tuft of grass where it showed above the snow.

Despite his hunger, the big cat paused. He must remain unseen. He tested the wind; he must approach into it. And, above all, he must plan his stalk so as to intercept one of the feeding animals when it was close to some kind of cover.

Unaware of his presence, the elk wandered back and forth from one bit of tempting browse to another. The cougar began his approach, walking softly in the shadow of a tree when it was available, using the shelter of a slight depression or towering boulder when it was not.

At last he was only 100 yards away. He paused in the shelter of a cherry thicket, crouching tense and alert as he plotted the probable course of the feeding animals. They were headed toward a granite outcropping 50 yards long and 10 yards wide with great slabs and chunks of the gray rock lying along each side. At the downhill end of the rock there was a clump of mahogany. The great cat started down ever so slowly, his belly brushing the hard-packed snow. He took advantage of every bush and rock with instinctive patience. This was the crucial part of the stalk. If he could see the elk, they could see him, too.

At 50 yards he paused again to peer cautiously over a thick sagebrush. Several of the elk had turned slightly away, angling downhill toward a patch of bitterbrush. But one cow was still headed toward the rocks. The cougar moved ahead to intercept her. He was a noiseless black shadow on the snow, blending with other shadows, moving so slowly that he didn’t seem to move at all.

At last, he reached the rocks. The cow was now out of sight behind them. He crept along one side, mindful not only of his quarry but also of the other elk beyond, which might see him and spread an alarm. He reached the far corner of the outcropping and crouched in the shadow of a boulder beside it. He couldn’t see the cow, but he could smell her. He could hear her tearing the young twigs off the mahogany. He could hear each step, coming closer. His muscles tightened.

Finally he saw her head and shoulders come around the rock. She was only 20 feet away. But wait! He must have a clear path through the mahogany. The cow moved ever so slowly. Eventually she paused beyond an opening to feed again.

The great cat crouched tight and leaped, like the missile from a catapult, shooting toward the cow elk in the moonlight. She heard him strike the ground. She started to whirl away but she was too late. In another bound he was on her. He was on her shoulders, where a cougar must always be to kill an elk.

He threw a muscular forearm across her withers and locked his massive canines on the back of her neck, The 2-inch claws dug into the cow’s tough hide and the hard, thumblike protuberance above his wrist pushed it against them. His back claws dug against her near side, caught, and pushed him up. He was on her back, his forearms gripping her head and neck, his back claws digging into her sides like spurs.

The elk weighed 450 pounds to the cat’s 160. She could easily leap over a blowdown that was 4 feet high and 6 feet wide. She was incredibly strong and active, and killing her would require all the lion’s strength and skill. Cougar are sometimes fatally injured in encounters with elk, and healthy animals very often escape.

If the cow had been a deer, the big cat could have bitten into the spinal column just behind her head and killed her easily, instantaneously. But an elk’s neck muscles are too thick, the bones too hard. Now the cat’s big teeth gripping the back of her neck gave him purchase; they locked him to her. His back legs and claws provided balance and power to pull back. And the claws of both front feet were already biting into the cow’s face.

All of this took only a fraction of a second, but the elk reacted instantly, too. She whirled, reared like a bucking horse, and plunged downhill. She hit a rock, slid, fell, regained her feet, plunged through a clump of the iron-hard mahogany in a vain effort to scrape the big cat off, and lunged downhill again. But the cougar’s forelimbs, pulling the cow’s head under with tremendous strength, succeeded. There was a snap. Her neck was broken in midleap. She was dead when she struck the ground.

The cougar fed from a hindquarter, tearing out great gulps of flesh and swallowing them whole because all of a cougar’s teeth are meant for cutting and tearing—it has no molars. Daylight had come by now and the pale winter sun rose while the mountain lion was still feeding. Satisfied at last, with 25 pounds of warm elk meat in his stomach, the cougar licked his bloody paws and wiped his cheeks. Then he covered the elk carefully to keep off keen-eyed ravens and climbed slowly up the hillside until he found the south-facing boulder. He curled up in the sunlight and went to sleep.

From time to time as the shadow of a tree crept around the hillside the male cat moved into the sun again. He was content. Unless disturbed, he would remain here, loafing in the sunshine, curling up into a tight, fuzzy ball at night, until the elk was consumed.

At midafternoon something woke the cougar. He raised his head to look for ravens. There were none in sight. Perhaps a coyote was slipping in to feed on the kill. No. It was a sound unlike that made by any animal. He heard it clearly now, steady footsteps crunching in the sunwarmed snow. Cautiously, he rose to his forelegs. He saw the source. Two men and two dogs, still nearly a quarter of a mile away, were following his own tracks toward the kill. The hunter was the hunted now.

Without a sound, the big cat rose and slipped around the corner of the rock. Using it for cover, he started walking swiftly away through a patch of bitterbrush. The hunters and their dogs came to the elk. The evidence was clear. “A lion kill!” one of the men exclaimed and quickly unleashed the hounds.

The great cat crouched tight and leaped, like the missile from a catapult, shooting toward the cow elk in the moonlight. She heard him strike the ground. She started to whirl away but she was too late. In another bound he was on her.

They circled the kill, found the tracks leading away and followed them to the rock. Here the fresh scent hung heavy in the air and the tracks that led away were fairly smoking. The hounds broke into a run, baying constantly. The men followed as rapidly as they could.

The cat was running now. It had heard the dogs. But it was heavy with food, and after a short sprint the hounds gained rapidly. Soon they could see their quarry. Their baying became wild with excitement. For half a mile the cougar led them down and around the mountainside. Then, panting, it came to a big yellow pine. Without a backward glance it ran rapidly up the trunk to a large horizontal limb 40 feet above the ground. Here it crouched to watch with baleful eyes the rapidly approaching dogs. At the foot of the tree, they set up a continuous baying. One of the hunters, hurrying with all his strength around the rough slope, gasped, “Treed!” to his companion.

At the pine, the two hunters removed their packs. One of them took a gun from his. But it was not a conventional gun. Powered by a 32-gauge blank shotgun shell, it fired a .50-caliber syringe with a barbed 1-inch hypodermic needle on the front and a fringed nylon stabilizer at the rear. In the barrel of the syringe a tranquilizing drug (phencyclidine hydrochloride) was backed by a rubber plunger and a light, self-detonating explosive charge.

Aiming at the cougar’s hip, Dr. Maurice Hornocker fired. The syringe went true. The needle drove into the muscle. The charge inside the dart fired, pushing the plunger ahead and injecting the drug. The other hunter, Wilbur Wiles, said, “Perfect!”

The lion crouched calmly on the limb, glaring at the hunters and their noisy dogs. But the hunters were busy. They took scales, a nylon net, ropes, tags, climbing spurs, and other items from their packs. From time to time one of them glanced at his watch and then up at the great cat. At last Wilbur said, “Ten minutes,” and led the dogs away from the tree to tie them while Maurice put on the climbing spurs.

Animals on the ground can be immobilized and knocked out completely. This won’t do for cougars, which may be 60 or 70 feet up a tree when captured. If they fell they would be injured or killed. So the drug used and the size dose, which is carefully adjusted to the estimated weight of each animal, merely calm them. They remain conscious but can be handled safely.

Maurice climbed the tree until he could look straight into the yellow eyes of the big cat—an animal heavier than he was. He tied a rope around it, shoved it off the limb, and lowered it to the ground. There he and Wilbur weighed and measured it. They attached numbered aluminum tags and color-coded plastic streamers to each ear and put a nylon rope collar carrying a numbered, brightly colored plastic tag around the animal’s neck, thus making sure that if one identification mark were lost another would remain.

Weighing, tagging, measuring, and the careful examination of the cat that accompanied this, plus meticulously recording each item in a notebook, took something over fifteen minutes. At the end of this time the cougar showed signs of recovering. The men stepped back. Ten minutes later, the lion struggled to his feet, looked around as though puzzled, and walked groggily away. He would remain under some effects of the drug for another half hour or more, but to inexperienced eyes he would appear completely normal.

A Scientific Hunt

For five winters, from late November through April, Maurice Hornocker and Wilbur Wiles have studied cougar in a rugged area of 200 square miles in the Big Creek drainage of central Idaho. Each winter they have walked from 1,000 to 1,200 miles.

Even on a park path, 1,200 miles is a long way—three times the distance from Los Angeles to San Francisco. There was no path for most of the miles Maurice and Wilbur hiked, wearing snowshoes at times and at others carrying them where the slope was too steep or the brush too thick to permit their use. They forded icy streams, wallowed through deep snow, crawled over logs, scrambled up rocks, felt their way around cliffs, and climbed slopes so steep they could pull themselves up only by hanging onto the bushes.

Unlike many other large animals, cougar can’t be watched from a distance or observed from a blind. They are too secretive. Many men who have spent half a lifetime in cougar country have never even seen one. The only chance to learn their mysterious ways is to follow tracks in the snow, studying the evidence left there and eventually, usually after many hard miles, releasing hounds to chase the maker of those tracks up a tree or onto a rock ledge. Only with the aid of dogs can cougar be captured consistently.

Why bother? Because we know so little about the big, handsome cat and its impact on the prey animals that support it—in the Big Creek study area, mule deer and elk.

The cougar originally had the widest distribution of any mammal in the Western Hemisphere—from the Straits of Magellan to northern British Columbia and from the Atlantic to the Pacific. It thrived in jungles and on the desert, at sea level and among the high mountains, in the Florida Everglades and in the rain forest of the Pacific Northwest.

As America was settled, a myriad of legends, stories, and myths sprang up about the cougar. It occupied a prominent part in the folklore of the frontier as that frontier moved inexorably from the Atlantic Seaboard to the Pacific. Yet, strangely, very little was actually known about it. The books are full of conjecture on every phase of its activity from hunting to mating and rearing young.

Finally, in 1964, an intensive, scientific cougar study was begun on the Big Creek drainage in the Idaho Primitive Area, 144 million acres of the wilderness that is essential to maintain a lion population. There are few spots left with enough lions to make such a study worthwhile. The study was sponsored by the Idaho Fish and Game Department; the University of Idaho; the University of British Columbia; and, since January 1968, by the Idaho Cooperative Wildlife Research Unit and the U.S. Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife.

Financial assistance came from the American Museum of Natural History through its Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Fund, the Boone and Crockett Club, the New York Zoological Society, the National Wildlife Federation, and the Carnegie Museum. And the man chosen to head the cooperative project was Maurice Hornocker.

Blue-eyed, dark-haired, slender, and muscular, Dr. Hornocker at 39 gives the impression of being as taut as a drawn bowstring and as hard as a nail. He majored in wildlife management and ecology at the University of Montana and got his master’s degree there. His doctor’s degree came from the University of British Columbia where he studied under Dr. Ian McTaggart Cowan, one of the world’s foremost wildlife ecologists. His doctor’s thesis, naturally, was on cougar. And for six years at Montana he assisted Drs. John and Frank Craighead in their famous study of the grizzlies in Yellowstone National Park, Maurice began his work with cougar at Montana, perfecting the technique for tranquilizing and capturing them. He took a contract with the University of Idaho and the Idaho Fish and Game Department in 1964 to conduct the Big Creek cougar study, and in 1968 was named leader of the Cooperative Wildlife Research Unit at the University.

His first break in the study came when he found Wilbur Wiles for an assistant. Wiles had spent twentyfive years in the roadless Big Creek country and knew it like the back of his hand. In addition, he was an experienced cougar hunter. He was an excellent woodsman, a tireless hiker, and a congenial companion. “Wilbur’s contribution to the study can’t be overemphasized,” Dr. Hornocker told me. “Many things simply could not have been done without his help.”

Each fall Maurice and Wilbur set up camps at six- to eight-mile intervals in the study area and, using pack horses, stocked them with food, cooking equipment, fuel, sleeping bags, and other essentials. They might follow an animal until dark with the temperature below zero. Having food and shelter within reasonable distance could be vitally important. And hunting day after day for months, as they did, made adequate food and rest essential

Their headquarters were the Taylor Ranch at the lower end of the study area, 9 miles from the spot where Big Creek flows into the Middle Fork of the Salmon River. Here, 34 miles from road’s end at the Big Creek Ranger Station, Jess and Dorothy Taylor guided anglers in the summer, hunters in the fall, and extended unlimited hospitality to Wilbur Wiles and Maurice Hornocker.

Cougar Country

The study area was on the winter range of the deer and elk that are forced down into the Big Creek valley by the deeper snow at higher elevations. Cougar, of course, stay with their food supply. Each year when the snow came, Maurice and Wilbur started hunting, carefully working out all the side drainages near one camp, then moving on to the next.

When they found a cougar track they followed it, checking any kills the big cat might have made, observing its movement as recorded in the snow and, if possible, catching it in a tree, on a rock ledge, or in a cave where the animals occasionally took refuge from the dogs. An average of 4.3 days of grueling hunting and tracking went into each capture. Each time they caught one, Maurice and Wilbur weighed, measured, and tagged it or, if they had caught it recently, merely recorded its number, condition, and the location of the capture.

One of the surprising things revealed by the study was that there was a stable population of adult, resident cougars, each with its own well-established territory which all the others avoided. Migrant lions, usually young adults seeking territories of their own, might pass through, but they didn’t stay. By the end of the 1966-67 winter, the team had caught and marked the entire adult cougar population of the study area. No new adults were caught during the two following winters.

Forty-six lions were caught and tagged in the five years, and 31 of them were recaptured a total of 109 times, making a total of 155 captures. It was these repeated captures that established the territoriality of the cougar. There was one adult lion for each 13.3 square miles within the 200 square miles of the study area. Maurice and Wilbur caught one male, No. 3, eighteen times, always within the same area of 25 square miles.

Females wander even less. The largest area occupied by any female was 20 square miles; the smallest, 5. Maurice pointed out, however, that these represent minimum winter home range sizes; the ranges may actually be somewhat larger.

I asked him whether cougars changed their escape tactics after being caught several times. He said their reaction was always the same—they simply did their best to run away from the barking dogs and when flight failed they treed.

Next I asked whether any of them had attacked men or dogs. “Not once,” he said. “In 155 captures, not one lion offered to attack.”

“Then,” I said, “they must be dreadful cowards.”

Maurice corrected me. “There is no such thing as cowardice among wild animals,” he said. “The cougar’s innate behavior is to avoid men and barking dogs. This is the result of evolution. For thousands of years the lions that chose to stay and fight perished; those that ran survived.

“The same innate behavior controls their attitude toward each other in relation to their territories. They don’t fight to maintain them; they avoid each other. The reason is obvious. A lone predator whose life depends on its ability to stalk and kill big game simply can’t afford to risk being crippled in a fight. Fighting may occur at times, but, in a stable population, I believe it is extremely rare.”

Deer and elk provided nearly all the food for the lions in the study area in winter. Only two bighorn sheep kills were found, although approximately 125 sheep were present. Maurice and Wilbur found the remains of three coyotes and one Rocky Mountain goat killed by cougars; rabbits and other small mammals were also included in their diet. Porcupines, which cougar kill and eat regularly in some regions, were not present in the study area. The big cats killed deer of both sexes and all ages, but they preferred young elk and avoided mature bulls. It is easy to understand why: With his massive antlers and up-to-800-pound weight, a bull elk is a formidable adversary.

One of the purposes of the study was to assess the impact of a population of lions on a population of big-game animals. The myth-shattering conclusion was that “predation by lions is inconsequential in determining ultimate numbers of elk and deer.” Due to a series of mild winters, the elk and deer populations increased steadily during the five years. The resident cougar population, however, remained constant. The ratio of lions to deer and elk dropped from 1: 135 in 1964-65 to 1:201 in 1967-68.

The true limiting factor here, as on most big-game ranges, is food. There is abundant summer forage, but browse plants on the restricted winter range are heavily overused. When the weather is mild, the deer and elk get by all right; during hard winters, many of them starve. This in itself is tragic, but the severe overuse of the range damages it to the point where it requires years to recover—and for the game population once more to reach its former level.

Young lions reared on the study area wandered off seeking territories of their own as soon as they were self-sufficient. Two of them tagged here were later killed more than a hundred airline miles away—in different directions. The researchers captured one young female in a territory left vacant by the death of an adult and believe she probably will stay there.

“Territoriality,” Dr. Hornocker wrote in a report on the study to date, “appears to be the primary factor in regulating numbers of lions in the Idaho Primitive Area. The number of adults well established on territories remained unchanged from year to year, despite the fact that four to six kittens were born into the population annually.”

Many questions about cougar have been answered during the five winters of research, but more remain to be solved. Foremost among them is: How often does a cougar kill a deer or elk?

Nobody really knows the answer, although there has been endless speculation on the subject. Barroom wisdom has it that each mountain lion kills a deer a week. Dr. Hornocker’s research—following every cougar track seen for five winters and carefully recording every kill—indicates that this figure is too high.

His No. 7C and her three 70pound kittens killed one elk in twelve days. His No. 4 and her three 70-pound kittens killed four deer in eighteen days. He gathered evidence to show that in winter the interval between kills of deer by some cats may be ten to fourteen days, longer after killing an elk. And during the summer cougar eat more of the small mammals, such as ground squirrels, that are available then.

But the weakness in all data collected so far, whether by Dr. Hornocker or by the casual cougar hunter is this: You follow a cougar’s tracks in the snow and jump it off a kill on which, if left undisturbed, it might have fed for several more days. So it kills another animal sooner than it normally would have.

During this winter and the next, Maurice and Wilbur will catch every resident cougar in the study area and fit it with a collar containing a tiny radio transmitter. Each transmitter will send a coded signal, and six receiving stations on high points will receive these signals. There are problems to overcome in the use of radio tracking equipment in such rugged country and many bugs will have to be ironed out. But with a functioning system and by making a triangulation from two receivers, the researchers will be able to tell approximately where each cat is. If one stays in the same spot for seyeral days they will know it has made a kill. When it moves on to resume hunting they will examine this kill, then follow it via radio until it makes the next.

Completely undisturbed, the big cats will go about their normal business. Their hunting will be entirely natural—and for the first time ever we will know just how many biggame animals cougar actually do kill during the winter months. This information will be extremely valuable in the management of both the lions and their prey.

Fair Game

Like many other states, Idaho formerly paid a bounty, $50, for each cougar. The bounty was removed several years ago, but more of the big cats are killed now by sportsmen than were taken formerly by professional hunters. More people with more time and more money, and the new go-anywhere vehicles that take most of the work out of cougar hunting have all contributed to the change. The same thing has happened in the other states that have enough mountain lions to justify hunting.

Some of them, including Washington, Utah, Colorado, and Nevada, have responded by giving the cougar game status. British Columbia has done the same. Oregon has closed the season completely until the Game Commission obtains more information. But in the other Western States where cougar still occur they are legally classified as predators. Any number may be taken at any time and by any means.

Dr. Hornocker has strong feelings on this. “The cougar is a splendid game animal,” he told me. “It is one of our finest trophies. Sport hunting is certain to increase.

“I think we should hunt cougar, but we should manage them like we do other game animals, too. If we don’t, the day will surely come when there are no cougar left to hunt.”

You can find the complete F&S Classics series here. Or read more F&S+ stories.