The Evolution of Winkler II

We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn more › A...

We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn more ›

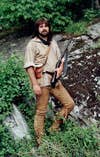

A little bit back, I was hunting groundhogs in the former Confederacy, and happened upon a young farmer. We got to talking about this and that, and he allowed as he farmed, and was a blacksmith on the side and made primitive knives and tomahawks. Interesting, I said, because we’re not real far from Blowing Rock, North Carolina, where Daniel Winkler works, and I’ve been to his shop when we did a TV show about him.

The young farmer’s eyes got as big as elephant turds.

“You…know…Dan..Winkler?” he gasped.

If I had said that I had lunch with God every Wednesday he would not have been half as impressed, and the rest of our time together he kept looking at me slantendicular.

That gives you some idea of the repute in which Dan Winkler is held. Or, I could tell you that when he was making buckskinner knives, and exhibited at the New York Knife Show, ten minutes after the show opened his table would be stripped bare except for a couple of demonstrator knives which he and his partner, Karen Shook, refused to sell so people could at least get a look.

Daniel Winkler has had one of the more interesting careers in the world if knifery. He got his start in the 1970s because he was a buckskinner and couldn’t get the things he wanted. So, being clever, as they say in the South (up here we’d say good with his hands), he made them. He went to museums, and looked at the real tools and weapons that frontiersmen carried, and then scavenged steel and wood and rawhide and an anvil and a forge, and he was off to the races.

Daniel made his first knife in 1975. Then people started buying them, and in 1988 he became a full-time maker. His work was unusual because while it appeared primitive and had Frontier Funk, if you looked closely it was very finely made. No frontier blacksmith ever worked at the level he did.

His other asset was Karen Shook, who was a genius with leather. Her sheaths could be plain or fancy, whatever you wanted, but they all looked as if they had just been yanked off David Crockett’s belt. Like Daniel, she never repeated a design, and did fantastic things with the simplest of materials.

Things might have gone on like this indefinitely, except in 1994, during the Gulf War, he was approached by a member of a Naval Special Warfare Group, also a North Carolinian, who wanted Dan to build him a combination Combat/Breaching hatchet. In other words, a tomahawk. Now I’ll let Daniel tell it:

“They (the SEALS) were not happy with what was on the market. It was either too heavy, too big, or junk. They wanted a design that would work well, and had a bit of historical flair. We did the development and intended to contract the manufacturing to another company, but we found that other folks had their own idea of how to do things, and I wouldn’t accept their changes. We decided that if we were going to get involved we would set up our own manufacturing facility where we had control.

“The people who buy our knives and hawks literally put their lives on the line based on the performance of their equipment, and we were not willing to cut any corners. [Note: Daniel refuses to discuss what his SEAL customers do, but apparently even the routine stuff is absolutely hair-raising.]”

Daniel and Karen started a shop, and trained the people who ran it, and expanded their line to include a variety of tomahawks, belt knives, and daggers.

“As we worked with SOF teams our reputation grew, and more and more operators in the high-speed community wanted our products. The growth has continued for the past 12 or 13 years. We still devote about 65 percent of our production to the military.”

Eventually, the new knife line became so successful that Daniel and Karen decided to put the buckskinner knives on hold. They were, to put it mildly, labor-intensive, and could not be turned out fast enough. Winkler II designs, which are made by stock removal rather than forged, are standardized, and can be produced much faster.

When Daniel began designing for SEALS and similar folks, he turned for inspiration to the knives people used on the frontier, where you wore one every day of your life and used it for just about everything. His designs, as a result, do not look “military.”

He says: “My influence has always come from function. The historic designs I made as a bladesmith were working knives. I use the same thought process now. When a knife has too much going on it loses function ability. Usually, simple is better, and if we can add a feature like a glass breaker or a hammer pommel without negatively affecting the primary function, we’ve done well. Some of the old-time smiths followed function and some didn’t, just as smiths do now.

“A tactical knife is the one you have in your kit when you need it. It needs to be well designed to fit what you need to do, and it needs to integrate with other gear. The real professionals who put their lives on the line learn what works and what doesn’t. We don’t make an entry-level tool for anyone. We’re the guys you go to when you figure out that a lot of hype doesn’t work. TV and the movies have set the standard for what the public thinks a tactical knife is, and there are some real badass looking knives out there, but they’re not for the real world. The most useless piece of gear you have is the one that stays on the shelf when you go into the field.”

Which leads us to a special edition of the Winkler II Belt Knife, which we shall look at next time.