F&S Classics: A Hunt with Poppa

The author gets the outing with her grandfather that she always wanted—and much more

This story was first published in the February–March 2019 issue.

“IF WE DON’T find any squirrels, we’ll go back to the cabin and shoot them off the bird feeder,” my grandpa said as we walked into the woods, flashing me a wicked grin. Poppa wore a faded work shirt under denim overalls so bright they must’ve just come off the shelf at Tractor Supply. He topped the outfit off with a squat trucker’s cap, and he carried a shotgun in the crook of his elbow. It was only the first week of the small-game season, but this hunt was long overdue.

We eased down the two-track that bisects my uncle’s 40 acres, a hardwood lot sandwiched between the state highway and a wall of pines that marks the Hoosier National Forest. I carried a Savage .22, a choice Poppa thought foolish. The proper gun was an Italian-made 20-gauge, specifically the Charles Daly Field III he carried. It was a pretty little over/under that he’d rescued from a yard sale the year I was born.

Satisfied that we’d walked far enough from the cabin—about 50 yards—he lowered himself onto a dead oak beside the two-lane. The shotgun rested across his 85-year-old knees. I joined him, and leaned back to search the branches above. Soon my thoughts began to wander, as all hunters’ thoughts do when it’s time to wait.

A joke (or maybe it wasn’t a joke at all) about popping yard squirrels wasn’t the sort of thing Clarence Krebs indulged in when I was little. Poppa had always been stern, a German Catholic engineer with eight kids, then 17 grandkids, but no time for nonsense. I spent my early years avoiding him, or saying little when that didn’t work.

Then Poppa retired, which cheered him up considerably. But the process was like a beech letting its leaves drop—it took a while. Jokes become more common, though I could still say the wrong thing. Once, I told him I wanted to be an architect; he made it clear I didn’t want to do that. Architects, he said, dreamed up problems that engineers had to fix. I just nodded. Later, when he heard I wanted to be a writer, he didn’t say anything at all.

A RUSTLE drew my attention to a high branch where paws fussed behind a screen of leaves. I whispered, then remembered Poppa probably wouldn’t hear if I fired three distress shots into the air. So I tapped his shoulder and we argued over who would shoot. I won by setting my rifle aside. The squirrel twitched, and Poppa pulled the trigger.

To meet me here, he drove over the Ohio River, across a bridge he’d helped create. Poppa often spends weekends looking after the farm and faithfully observing happy hour before supper. Once, when I’d grown old enough to crack a beer without getting in trouble, Poppa taught me to drink it by tipping my head instead of the bottle. He insists it’s cooler. Another time, he’d called me to sit beside him on the porch.

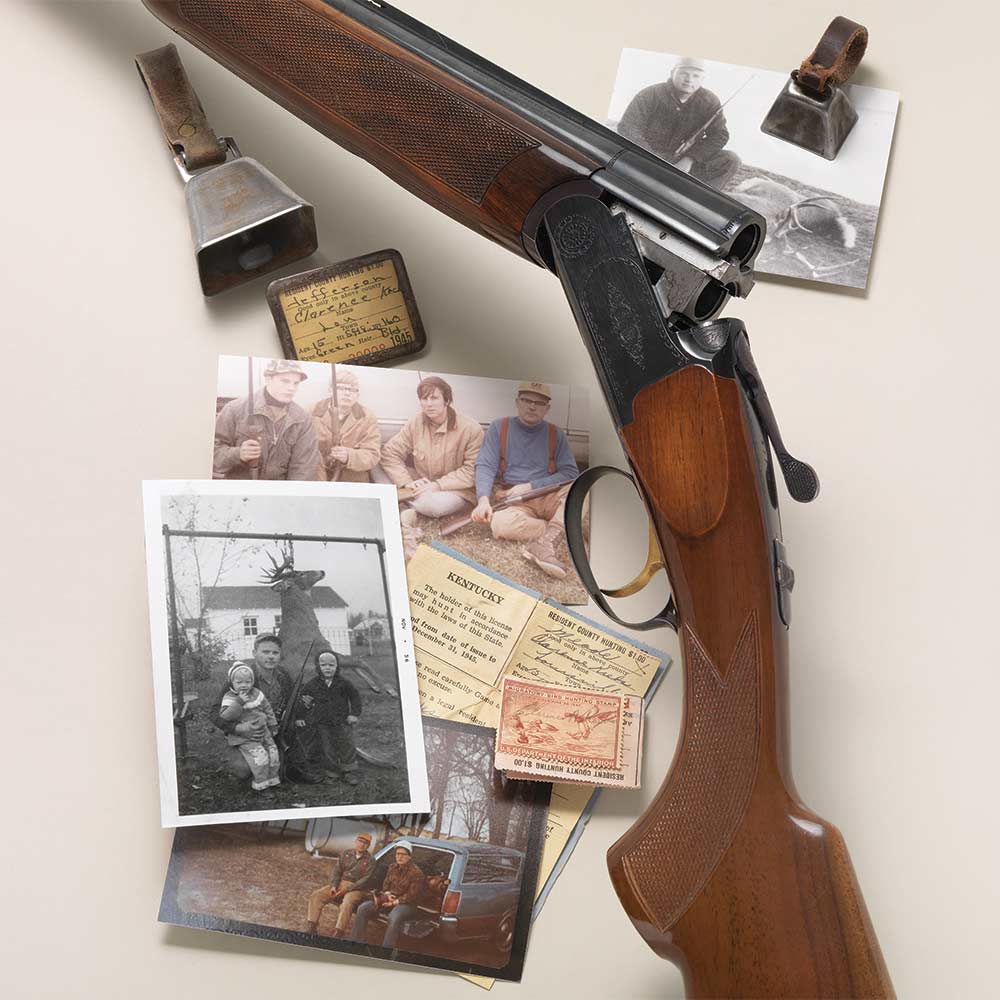

“I know you like old things,” he said, placing a burlap shot sack in my hand. Inside were two battered bells on leather straps, a brass quail call, and a metal pin that read “State of Kentucky” in raised letters. The pin held Poppa’s 1945 hunting and fishing licenses, lettered in a careful hand, and a duck stamp from 1946–47. Each had cost $1. I considered the dates. His dad had died in 1944, just after Poppa turned 14. He’d hunted by himself, mostly, in ’45 and ’46.

“You don’t have to keep them,” he said. “I don’t know what you’ll do with them.”

I protested and held them closer, heirlooms that some might mistake for junk. Buried down the hill from where we sat were Poppa’s two Brittanys. He’d told me often about the travesty of modern e-collars, when nothing was so sweet as those clanking bells. Beside us sat my grandma, lost in the fog of Alzheimer’s.

THE LEAVES EXPLODED, and the squirrel scrabbled around the trunk uninjured. Poppa’s face clouded. I had guilted him into this outing, our first squirrel hunt together. He’d taken some of his grandsons squirrel hunting when they came of age, but none of them took to hunting. His granddaughter did, but he never asked me to go. So when I was almost 25, I demanded a squirrel hunt with my grandpa. In the end, he killed one, and I never took a shot. It was perfect.

A few years later, Poppa called me down to the workbench, where a gun case lay. Inside was that pretty little over/under. On the trigger guard was a tag in the same hand as the hunting licenses, a slight wobble to it now. It read, This 20 gauge, fixed choke, is for Natalie. —Poppa

Later I learned that he’d intended to leave me the Charles Daly in his will. He’d labeled it and locked it up until that unhappy day. Instead, my dad persuaded him to get some joy out of the transfer and give it to me himself. So he did. With each gift, he passed along his memories to someone hungry for them before they didn’t mean anything to him or to anyone else.

Lately when I see him, usually with a glass of Wild Turkey in hand and hearing aids turned up, he starts off saying, “Aw, you’re not still hunting all the time, are you? Running all over the place? It’s not right. You don’t want to do that job forever.”

It’s part jest, part genuine disapproval. These days, I don’t nod. Instead, I tell him, with a wicked grin on my face, that if he disapproves so much, he shouldn’t have given me his shotgun.

You can find the complete F&S Classics series here. Or read more F&S+ stories.