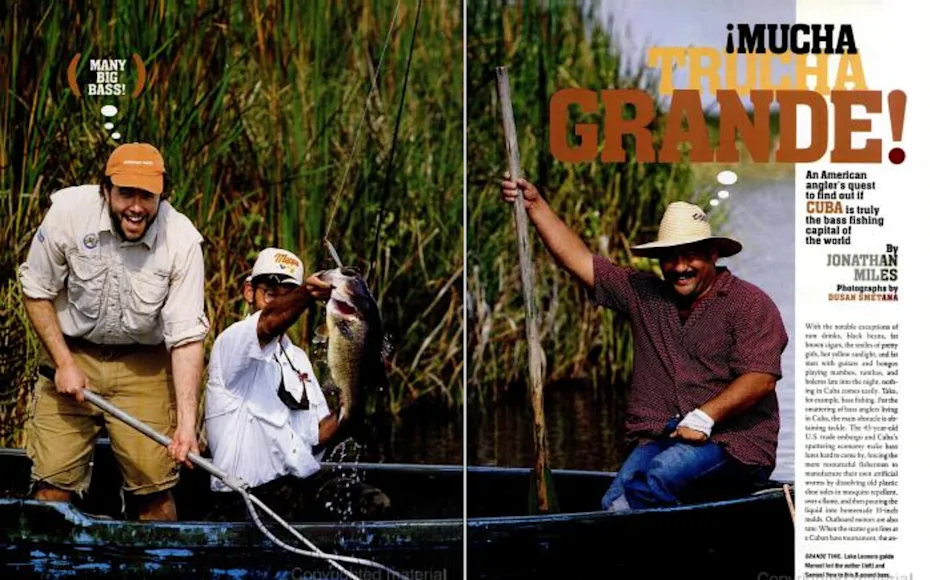

With the notable exceptions of rum drinks, black beans, fat brown cigars, the smiles of pretty girls, hot yellow sunlight, and fat men with guitars and bongos playing mambos, rumbas, and boleros late into the night, nothing in Cuba

comes easily. Take, for example, bass fishing

. For the smattering of bass anglers living in Cuba, the main obstacle is obtaining tackle. The 43-year-old U.S. trade embargo and Cuba’s sputtering economy make bass lures hard to come by, forcing the more resourceful fishermen to manufacture their own artificial worms by dissolving old plastic shoe soles in mosquito repellent, over a flame, and then pouring the liquid into homemade 10-inch molds. Outboard motors are also rare: When the starter gun fires at a Cuban bass tournament, the anglers fan out in rowboats, thrashing the water as they paddle like hell to be first to the sweet spots.

For American bass anglers, the main obstacle is U.S. law, which effectively prohibits travel to Cuba. If you can get past that, however, there are the connect-the-dots travails of access. To fish one of Cuba’s best bass lakes, for instance, requires a many-legged flight that includes a layover in a third country; then a 12-hour drive across the island on a two-lane highway hemmed with horse-drawn wagons, loping dogs, bicyclists, hitchhikers, and broken-down Russian mini-sedans; then a grueling, spine-compressing, two-hour drive on a pitted rural pathway bisecting sugarcane fields; and finally, at water’s edge, a formal transaction with the lake’s governmental boatmen, who inspect your passport and count your cash and stamp some papers and then stamp some other papers inside a dirt-floored wooden cabin where a bass calendar hangs upon the wall across from a neatly stacked shelf of empty Cristal beer cans.

The obvious question, then, is: Why? Why melt your precious shoes down to worms? Why flirt with—or even flaunt—the U.S. Treasury Department’s ominously titled Trading With the Enemy Act? Why fly and then fly some more and then drive and drive some more, forfeiting your rental car deposit as you hammer the car’s undercarriage into road rut after road rut? Why stand there in the tropical dawn trying to figure out how to get said rental car unstuck from its perch atop some railroad tracks? Why this just-shy-of-epic quest for a fish that about 90 miles to the north is so readily and conveniently available in almost every Florida park, pond, and puddle?

There is a very good and logical answer: Angling rumor has long held, over these many years of intransigent political standoff, that Cuba may harbor some of the best big-bass fishing in the world with a fair claim to the next world-record largemouth.

The Road to Trucha

Havana is one of the great cities of the world, sublimely tawdry yet stubbornly graceful, like tarnished chrome—a city, as a young Winston Churchill once wrote, where “anything might happen.” Or at least this was what I told my pal Bruce Browning upon our arrival there, just before informing him that, because there are no bass in Havana, we would be leaving within the hour. As a journalist, I’d been to Cuba twice before, and though I’d circled every mention of bass fishing in my guidebooks, I’d never been able to fish there. But I’d talked about it a lot, mostly with Bruce, a professional bongo and conga drummer from Mississippi who shares my fascination with overweight fish. Cuba or bust, we pledged one night. Now we were making good on it.

In Havana, our party doubled: Dusan Smetana, a photographer, joined us, along with Samuel Yera—a three-time Cuban bass-tourney champion and perhaps the best bass angler in Cuba—who’d offered to guide us on our cross-island bass odyssey. We piled our rods and tackle bags into a rented Toyota Yaris, a roundish microcar that would be ideal for parading Shriners but that shouldn’t be marketed to traveling bass fishermen. As we motored out of Havana, our kneecaps bumped our chins. The boys in the backseat swung their heads on the bumps to avoid getting eye-gouged by the rods rattling loosely between them. It was a decidedly Marxist (Harpo, not Karl) start to our trip.

We were going east toward Lake Hanabanilla, a deep, 7,900-acre impoundment in the Sierra Escambray mountains. “This,” Samuel told me, “is the best lake in Cuba for the big bass. Last year, an Italian tourist caught a 17-pounder on a worm there, and back in the ’80s, an American caught a 20- or 21-pounder. An uncertified catch, though.” A former civil engineer, Samuel is soft-spoken and fine-featured, with the bearing and appearance of a campus intellectual, and while he’s a keen conversationalist on a broad array of topics, one subject swims constantly through his brain: bass, or as it’s called in Cuba, trucha (which in a vagary of language means “trout” to most Spanish speakers). More formally, it’s known as Lobina negra boquigrande. In this case, the obsession is inherited. Samuel’s father, Jose Manuel Yera, was the national bass champion in 1971 and ’72, and Samuel’s earliest memory is an image of rods and reels and worms and glittery lures. “For me,” he said on the drive, as the Cuban countryside passed by in the dark, “it was a sickness for life.” I told him that Bruce and I knew something about the sickness, and Dusan nodded knowingly. We were like a rolling support group.

Tucked into the high, pine-carpeted slopes of the Sierra Escambray, where it’s cool even at noon and where the early-morning mist leaves a teardrop on every last green leaf and needle, Hanabanilla suggests lake trout more than bass-it almost seems too pretty for largemouths. Our quartet spent most of the next morning admiring it, waiting on two Triton bass boats with 75-horsepower Tracker engines that the Cuban government’s tourism bureau recently purchased for the lake.

When the boats finally arrived, four hours late, we went at the lake hard, plugging at the shore structure with dark 10-inch worms and spinnerbaits, then trolling the old river channel with deep-diving crankbaits. The cobalt water here is startlingly clear, and with an average depth of 100 feet, it’s unusually deep for a Cuban lake. A few scattered and smallish afternoon catches kept fish-despair at bay, but the action was slow. The fish finder showed the bass suspended down in those depths, hanging low and motionless in the water

Despite the un-basslike scenery, I trusted Samuels testimony about more typical fishing days at Hanabanilla. Still, I couldn’t help wondering: Was I the victim of dusty old hype? Was Cuba really the forbidden mecca of bass fishing, or was it, like areas in Mexico, just a patchwork of boom-and-bust lakes about which the breathless rumors always lag a few years (or decades) behind the reality?

These questions weighed darkly on my mind until close to midnight, when wandering the nearby Spanish colonial town of Trinidad, the four of us turned a corner at the Catedral Santísima Trinidad and found a street fair in raucous full swing, a salsa band sending drumbeats ricocheting around the plaza as dusky girls in wild headdresses danced on the cobblestones and teams of curbside bartenders muddled mint leaves for mojitos. After that, nothing weighed on my mind.

Until the following morning, that is. That’s when I had to drive the little clown car nine hours across Cuba’s eastern half. At one point we pulled alongside an oxbow to see what some anglers in float tubes were catching. I was hoping to see the freshwater eels that many Cuban handliners use for bait, and that may or may not be responsible for bass catches in excess of the official world record. (This is one of the juiciest rumors you hear about Cuba, that several or even many 22-pound-plus bass have been caught here—almost all of them by subsistence-fishing handliners throwing 1 1/2-foot eels. Samuel said these catches were probable but that he’d never seen one, and that, for the record, the official Cuban mark was 18 pounds.) The float-tubers were local tilapia anglers, however, bobber-fishing with scrawny nightcrawlers, and they seemed quite uninterested in either catching or conversing about bass.

As we talked, a barefooted 5-year-old girl appeared from a shack atop a nearby hill and began lobbing chunks of driftwood into the water. This looked fun, so I joined her. When the girl’s father came down to investigate, I explained that we were fishermen on our way to Lake Leonero, in Granma province, to try to catch trucha. His eyes widened. “¿Lago Leonero?” he asked with an envious grin. “¡Mucha trucha grande!” Opening his arms to demonstrate the size of the many trucha grande he was talking about, he looked like a man about to hug a 1,000-year-old tree. I sprinted so fervently back to the car that several cattle, including a bull, hustled out of my path. Bruce ran, too, but only because he doesn’t speak Spanish and assumed I’d been threatened.

Lago Leonero

Unlike Hanabanilla, Leonero looks like a bass lake. In fact, Leonero looks like the perfect bass lake, the one you would design if you were God and needed to answer a pious fisherman’s bedtime prayers. Long and shallow with coffee-colored water, dappled with lily pads and hemmed by 9-foot walls of cattails and bulrushes, Leonero sits in the middle of a vast and hard-to-access wetland in eastern Cuba, two difficult driving hours south of the nearest city of Bayamo. Leonero also lacks even the scantiest of amenities—there are no waterfront hotels here, nor lakeside restaurants where strolling string bands play “Guantanamera” and Eagles covers at your table. If you want to sleep at Leonero, you can wrestle a goat for a soft grassy knoll. If you want lunch, you bring it or catch it. And if you want to catch it, you park yourself in a creaky 14-foot wooden dinghy and let one of the lake’s lackadaisical boatmen paddle and pole you slowly through the broken jigsaw puzzle of weeds and water.

Big baits caught fish. Small baits caught squat. An American angler from anywhere other than Texas, Florida, or California might feel a twinge of arrogance when tying on a bratwurst-size lure but that quickly subsides.

JONATHAN MILES

We set out sometime after nine, focusing first on some narrow openings in the lily pad cover, pulling 10-inch pumpkinseed worms tenderly through the pad stems. It didn’t take long for those stems to cough up trucha.

“Big fish,” Samuel whispered, leaning over the gunwales as he waited for the bass to swallow the worm, twitching the line ever so subtly. I’d never seen a bass fisherman with such artistic form and studied patience. He seemed more Zenned-out bonefisherman than hyper-excitable, rod-heaving basser—until he set the hook, that is, which is when I realized that the behavior of a man with a hooked bass completely transcends personality and geography. Samuel hollered and grinned and cussed as he fought the fish, his rod bending into a good solid U as he pried the bass from the weeds, and I swear that when he said, “C’mon, c’mon,” he was speaking with an accent straight out of Eufaula, Alabama.

“Nice fish,” we said in unison, when he’d pulled it to the boat, because it was: 7 pounds 11 ounces, a hefty green football of a largemouth. The next bass was over 6 pounds, which set an unfortunate precedent—the 3- and 4-pounders we kept catching throughout the day felt like unqualified interlopers.

This is not to suggest that Leonero, where we fished for two days, was ever predictable. Patrolling the edges of the bulrushes yielded some of the bravura fishing you’d expect, but the open water was just as productive; at times, casting anywhere seemed as good as casting somewhere. Worms worked best in the mornings, and hard jerkbaits ruled the afternoons, but the deciding factor was always the lure’s size—the bigger the lure, the better the fishing. I should clarify, though, that the old saw about small baits catching small fish and big baits catching big fish didn’t apply here. Big baits caught fish. Small baits caught squat. An American angler from anywhere other than Texas, Florida, or California might feel a twinge of arrogance when tying on a bratwurst-size lure but that quickly subsides.

After two consecutive strikes right at the boat, and after scanning the flat expanse of water and registering no living creature save some peregrine falcons, scissorbill gulls, and savanna hawks, I asked the boatman how many bass anglers he’d taken out on the lake.

“Last year, eight,” he said. He thought for a while, then added, “The year before, three.”

Fish Music

Back in Havana, we huddled midday at the Bodeguita del Medio, a venerable saloon in the city’s old quarter where decades’ worth of signatures and rum-fueled graffiti cover the walls. We were drinking mojitos and talking about fish. More specifically, we were trying to pinpoint the giddy appeal of bass fishing in Cuba. True, we hadn’t caught any glaring trophies—nothing above 10 pounds, though I did hook a cinder block of a bass at Leonero that, lunging sideways in open water, snapped the 17-pound-test connecting us. Nor had we pulled in the numbers of bass that make for tongue-wagging brochure copy; I’m certain we never hit triple digits either day at Leonero. But this line of thinking, we decided, is knuckle-headed at best. Fishing can be qualified but not quantified, especially in Cuba, where almost nothing can be quantified.

How, then, to describe bass fishing in Cuba? Maybe like this: In a corner of the Bodeguita del Medio, with the street outside awash in sunlight, an old man with a guitar and an old woman shaking maracas launched into a set of old Cuban folk songs, drowning out our earnest fish talk. After a while, the old man passed out percussion instruments—more maracas, sticks known as claves, and a dried, hollow gourd—to us, and also to some Spanish girls who’d been languidly dancing and singing along with the musicians. I’m not sure what songs we all played that afternoon, but I can hear them as I type this. And when I close my eyes, visions of the guitar strings thrumming meld into visions of taut monofilament, images of the Spanish girls dancing meld into images of bass leaping on Leonero, seeming to uncoil atop the water, and I am brought to a place in my memory to which I yearn constantly to return: sunset at Leonero, with the croaks of bullfrogs and the whir of long casts keeping a slow, moody rhythm, the splash of topwater strikes like the steady crash of cymbals, with the coming Cuban night offering only more music, and the next day more fish.