_Editor’s Note – We have some exciting news: F&S editor-at-large T. Edward Nickens

has a new book out!_ The Last Wild Road: Adventures and Essays from a Sporting Life

is a collection of his best and most beloved adventures, essays, and columns from Field & Stream_._ _You can purchase the book online

, or wherever books are sold._ To celebrate, all week we’ll be sharing some of our favorite classic tales from Nickens, and there’s no better way to kick things off than with the story that inspired the name for the new book. “The Last Wild Road” originally ran as a two-part narrative in the magazine—in the Nov. 2004 and Dec. 2004–Jan. 2005 issues, respectively. What follows is part one of the adventure.

The last Arctic grayling of the day smacked an olive cone-head streamer at 10:30 p.m., just as the first blush of the northern Alaska twilight turned low clouds yellow and orange and pink. The fish was 3 pounds, easy—only slightly larger than the grayling I’d caught a few minutes earlier, and the one landed just a few minutes before that. I trudged across the cobble, scattering salmon fry from the shallows, and sat down in wet sand pocked with bear and wolf tracks. I was tired. Early that morning we’d woken in a makeshift camp perched high on a ridge overlooking the Yukon Flats. We had shared the panorama with a South African couple circumnavigating the world in a customized six-wheel-drive Land Rover, then picked our way north, through dense spruce woods and then alpine tundra, chasing willow ptarmigan with bows and casting dry flies to willing grayling. We hardly blinked when we crossed the Arctic Circle. We never slowed for the scenic vistas marked by roadside signs. Fish. Hunt. Fish some more. No time for tourist stops.

The day before we’d hunted spruce grouse in dense conifer and birch thickets, crossed the Yukon River, changed our first flat tire, and fished along the way, all the while skimmed with a slick of bug dope, sweat, and road grime. And the day before that more of the same.

Now I stretched out on the gravel bar, yawning, and thought: This is what I came for. Upstream, the Jim River flowed from the high ramparts of Alaska’s Brooks Range: downstream it braided through islands of gravel and sand. I had a tent pitched in the woods a mile away, fish for breakfast, bear spray on my belt, and nowhere else to be. I’d come for the biggest bite I could take out of Alaska in a single two-week period. And all because of the weirdest, wildest road you can imagine.

The Ultimate Road-Tripping Road

Three days earlier, I’d stood in the detailing bay of Gene’s Chrysler Center in Fairbanks, Alaska, where gear was mounded up beside two loaner Jeeps. With me were Scott Wood, a friend and fly fishing retailer from North Carolina, and Montana-based photographer Dusan Smetana. It took us two hours to fit it all in: three guns, three bows, eight fly rods, two reels, a case of shells, three pairs of waders, cold weather gear, rain gear, stoves, food for 14 days, dry bags, cameras, GPS units, binoculars, a satellite phone, a tow strap, and maps galore. On top of one Jeep we bungee-corded two spare tires on rims, two gallons of gas in bright red cans, stove gas, and a portage pack of tents and sleeping bags, “The Beverly Hillbillies go to Alaska,” I said.

“Yeah,” Wood countered, “but name one thing you would have left behind.”

And he was right: We’d be fishing for Arctic grayling and Arctic char, gun and bowhunting for spruce grouse and ptarmigan, driving, hiking, rafting, cooking, and camping. Together or apart, the two of us had hit the roads from Mexico to Canada, in pursuit of elk, ducks, grouse, trout, smallmouth bass, pike, walleyes, barracuda—you name it. But never had we gone after everything at once, and never to Alaska. “It’s the ultimate fun-bog trip,” Wood said, sounding slightly insane.

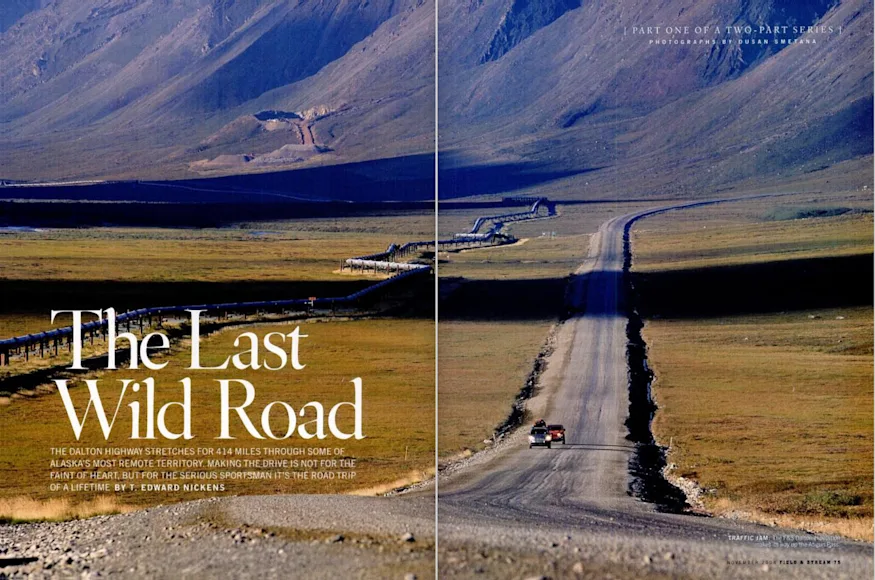

And it was taking place along the ultimate sportsman’s road-tripping road in North America—the Dalton Highway

. Thirty years ago, Big Oil built a 414-mile-long gravel road to parallel the Trans-Alaska pipeline, from Livengood to Prudhoe Bay on the Arctic Ocean. Originally called the “Haul Road”—and many Alaskans call it that still—the road was designed for trucking heavy equipment and manpower along the pipeline route. Renamed the James W. Dalton Highway in 1981, after a North Slope engineer, the road bisects some of the wildest country remaining in the Alaskan Arctic, and some of the best hunting and fishing lands in the Last Frontier. To the west lies Kanuti National Wildlife Refuge and Gates of the Arctic National Park and Preserve. To the east, Yukon Flats and the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and Preserve. Along the way the Dalton Highway crosses 34 major streams and rivers and 800 lesser creeks, their names as enticing as their waters: Yukon, Toolik, Ivishak, Sagavanirktok. All told, the road accesses nearly 40 million acres of federal wilderness—a region larger than Michigan surrounded by millions more state, federal, and Native American lands.

“The Last Wild Road,” by T. Edward Nickens, is available wherever books are sold. Lyons Press

It’s no gentrified byway. Tunneling through caverns of black spruce and white birch, arcing over vast plains of tundra, climbing and descending the mighty Brooks Range, the road is a jumble of mile after mile of gravel, then broken pavement, then new blacktop, then more gravel, plus wash-boarded hairpin turns, 12-percent grades, and asphalt bent into roller-coaster dips by the constant shifting of the underlying permafrost. Tractor-trailers roar up and down the Dalton, groaning with loads of airboats, johnboats, construction equipment, pipe, and generators the size of mobile homes. They spew contrails of dust, grit, and fist-size gravel sheared into shards the Dalton truckers refer to as “arrowheads.”

And those are just the man-made hazards. The Dalton Highway climbs from sea level to nearly a mile high, clawing its way through the Brooks Range. It can snow any and every month along the road. Ground blizzards make driving impossible. Even on sunny days, harsh winds can sweep across the tundra, closing the highway to all but herds of coastal plain musk ox. Scratch your nose at the wrong time and you might launch into boggy tundra, or into dark spruce woods, or into the utter nothingness that falls away from the road at Atigun Pass. Homemade crosses hammered into the gravel bespeak of dead truckers. Engine parts—and the occasional dead truck—litter the roadside.

We’d scheduled 14 days to mosey up the road. We would make camp in a different spot for 13 nights, sleeping indoors only once. Halfway through the route we’d take a side trip into the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, courtesy of a bush plane and a 14-foot raft. Back to the road, we would parallel the Sagavanirktok River to the Arctic sea village of Deadhorse, company town for the largest oilfield in North America. All along the way, we kept both hands on the wheel—at least when one of them wasn’t holding a rod or a gun.

Dream Hunt

By the time the Jim River receded in our rearview mirror, we’d settled into a daily road-trip regimen: up at six, light the stoves, have coffee followed by a breakfast colossal enough to fuel us till dinnertime. The most precious items in our food stash were a thick sheaf of vacuum-packed country ham and a 5-pound bag of grits. Smetana was a newcomer to Wood’s and my back-home staples, and he scraped the sides of the pot and poured leftover fish grease over his second helpings of grits and onions. “I see you’re from the Southern part of Slovakia,” Wood quipped the first time he saw this.

“Dixie, take me home,” Smetana replied.

After breakfast, we hurried to break down the tents, wash the dishes, and pile it all into the Jeeps. Then off we’d go. Hunt, drive, fish till the shadows started lengthening at eight, or nine, or even ten o’clock, and we’d ferret out a campsite away from the thick coat of dust that blanketed every leaf, stem, and designated campground along the Dalton. We pitched our tents atop overgrown trails and in gravel pits and four-wheeled down muddy side roads to tundra bluffs overlooking glacier-fed streams.

An uncountable variety of passions have driven men and women to the foot of the Brooks Range and beyond during the last few centuries—fur, gold, oil, the litmus test of wild country, the chance to camp in a place where it’s a good idea to spoon with a semiautomatic shotgun. Alaska itself is an American ideal, a totem of wilderness and self-sufficiency. Even to those who never wish to experience it firsthand, it’s a seminal part of the American psyche to know that Alaska is up there, vast beyond description, lush and severe and fertile and stark and somehow set apart. It’s a place for dreamers, and along the Dalton Highway, it seems, everybody wears their hopes on their sleeves.

At a small BLM outpost on the banks of the Yukon River I met a 50-ish Minnesota couple who moved four years ago to a tiny log cabin at the confluence of the Yukon and Hess Creek. They unabashedly declared that trapping marten in 50-below winters was simply a part of their aspiration of living off the land. The Belgian backpacker hitching on the side of the road had a simple enough dream: seeing as much as he could for as little as he could spend. The grime-encrusted figure on the BMW motorcycle with red gas cans lashed to the seat, the hunters stalking caribou—dreamers all of one sort or another.

It’s a stretch to call it a dream, but tops on my Dalton Highway wish list was stalking ptarmigan with a bow, out on the open tundra amid the blueberries, bearberries, cranberries, and cotton grass. North of the Yukon River, it’s archery hunting only within 5 miles of the road, not a bad idea given the omnipresent pipeline held aloft by heat-resistant trusses that keep it from sinking into the frozen tundra like a piece of hot coal in the snow. Admittedly, locals frequently describe these grouse-like birds as “dumb as rocks,” but felling a highly nomadic bird with a bow seemed no more or less crazy than gambling on gold dust or a hole in the ground. Plus, I figured they’d get along well with white flour, black pepper, and smoking hot peanut oil.

Like many northern wildlife species, from lemmings to hares to snowy owls, ptarmigan are everywhere or nowhere. Their populations are extremely cyclical. They range over hundreds of miles of territory. In the historic mining town of Wiseman, 3 miles off the Dalton Highway on the wide Koyukuk River, I talked to a trapper and subsistence hunter, Jack Reakoff, who figured we had our work cut out for us.

“When highly nomadic creatures are migrating, that means there are thousands of square miles of good range utterly vacant,” Reakoff said, as he snagged mosquitoes one-handed in a cabin filled with the mounts of Dall sheep and grizzly bear and racks of wolverine and lynx pelts. He is a trim, articulate man, Clark Gable with a wolf-tooth necklace. Reakoff was born in the Brooks Range, the son of an Alaskan bush pilot and guide, and he remembers hearing the chainsaws cutting down the trees for the pipeline, and the road scrapers coming through the woods. “My dad told me then, ‘That’s the beginning of the end for this country,’” he said, gazing at the cabin ceiling where large Alaskan maps were thumbtacked to the bare wood. Now, when he isn’t matching wits with wolves and wolverines, he sits on state and federal wildlife and resource committees. “I’d love to prove my dad wrong.”

The country plumbed by the Dalton Highway, he told me as I was leaving, “is a thin slice of everything the interior has to offer—it’s an incredible sampling of Alaska. Just bear in mind that it’s not the Discovery Channel up here. You can drive for miles and miles during caribou season and not see one. Ptarmigan are no different.”

But Wood and I were undaunted. North of the Yukon River, we bird-dogged the tundra like fiends, sweating in day after day of 80-degree heat, thanks to what locals described as “a 100-year heat wave.” Near Finger Mountain, a rocky outcrop favored by prehistoric hunters, a pair of peregrine falcons swooped low over the tundra on the east side of the road. Three ptarmigan flushed, and Wood stood on the brakes. “Let’s go hunting,” he hollered as the door chimed open and we glissaded down the gravel embankment. From the road the tundra looks like a rolling green blanket, as easy to traverse as a putting green. The illusion fades as soon as you put your boots on the ground. Arctic cotton grass grows in dense, foot-high clumps the size of basketballs. Walk on the tops and every third clump collapses. Keep to the spongy spaces between and you trip with comical frequency. We scoured Finger Mountain for an hour, then clawed our way back to the road, birdless. In three days we logged miles on the tundra, marching across the ridges at Connection Rock and Gobblers Knob through rain and fog, sloshing through knee-deep streams in calf-high rubber boots. Nothing. Not a bird.

Then one afternoon, we pulled the Jeeps onto a muddy track that ran beside an airstrip on the Chandalar Shelf, midway up the climb to the Arctic Continental Divide. Draining the headwaters of the Dietrich River, it’s a rolling plateau mounded by low, berry-cloaked hills. It was late and hot and one sore ankle already protested another tundra workout, but we were energized by this new country. We were far into the Brooks Range foothills now, at 3,100 feet, and perhaps the altitude would pay bonus points in ptarmigan.

A third of a mile from the road, Wood hissed, “Birds!” In the instant that I saw them—two ptarmigan silhouettes in the tundra, unmoving. I drew a judo-pointed arrow and settled the 25-yard pin on the bird. A stiff breeze sent tufts of cotton grass tumbling in the air. I moved the pin 3 inches to the left and released. The bird crumpled, and suddenly four more appeared out of nowhere.

With the twock of each bowstring, ptarmigan popped up like prairie dogs. We’d draw, aim, and suddenly the target would take off running. I took three steps and tripped, two steps and drew. There were birds down and scattered across a half acre of tundra, and arrows everywhere. Across a shallow gully Wood held up his ptarmigan. “Finally,” he hollered, “the gods smile!”

In 10 minutes we had seven birds on the ground. We knelt down to study each one, mottled brown feathers going to winter white, snowy feathered legs and feet. We gutted them on the spot, stuffed them into our vests, and headed back to the vehicles. I wasn’t sure what to think. Perhaps we’d guessed correctly: that the birds had hung up in the higher passes. That they would seek shade in the unseasonable heat. Or perhaps it was just as Reakoff had said: The Alaskan Arctic gives what it pleases, when it pleases.

Tourist Attraction

The climb across Atigun Pass ascends lush moss and lichen-spackled tundra to a moonscape of bare rock and scree piled up in 6,000-foot-high summits. We crawled up the pass in low gear, banks of fog and rain blanketing the slopes in near whiteout conditions. Every few moments the air would clear, and I sucked in breath as giant slopes of black boulders and gray talus rose from the edge of the road, scored by waterfalls pouring off the mountains. “Look at those guardrails,” Wood said. The aluminum fences were bent and battered by frequent rockslides that sweep across the road. “That’s gotta be a drop of 500 feet.”

Descending into the North Slope is like entering a different realm. Ridge falls away to serrated ridge, a world of rock and boulders that soon opens to an infinity of peaks clad in tundra and flecked with Dall sheep. Above Galbraith Lake we strung a tarp between the Jeeps and anchored the tents with rocks. It was a good place to dry out, take a breather, and take stock in the trip so far. We’d had fantastic fishing—the trophy grayling in the Jim River, Bonanza Creek’s surprise gift of 16-inch grayling smacking dry flies and bream poppers with equal abandon. And I had realized my ptarmigan dreams high on the Chandalar Shelf.

These are classic Dalton Highway moments, but the future of the road will be a test of how much use the region can handle and still remain Alaska. It’s easy to argue that one aspect of sporting life along the Dalton Highway calls for more management, not less, or at least an industrial-strength dose of sporting ethics. We’d been warned about the “circus” of caribou hunters that ply portions of the highway. Bob Stephenson, a biologist with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, had explained: The Dalton attracts increasing numbers of bowhunters because the caribou migrate right across the road, which makes packing out meat a less burdensome task. And a lot of beginning archers use the Dalton because access is so easy. Many hunters figure they can drop off their ethics at the border of the North Slope. “But I wouldn’t call a lot of them bowhunters.” Stephenson said. “You’ll see.”

Coasting into the foothills above the flat Arctic coastal plain, we did. I watched as a hunter hopped out of the passenger side of a pickup and used the camper shell as a moving blind as he closed in on a pair of bulls 50 yards off the road. He waved, a goofy Can you believe this? grin on his face, as if we ought to join the party.

One day I’d like to kill a caribou. They are the very sinew and tendon of the tundra wild, and stalking one across open country would rank as one of the great experiences afield. But I didn’t want these animals to die—not here, not within sight of the pipeline, and certainly not by hunters too lazy or ignorant to refuse to shoot them 20 yards from the road.

Deadhorse or Bust

After six days of hard traveling, it was high time to take a break. One of the best things about the Dalton Highway is the entrée it provides to even wilder country. Bush planes operate out of dirt airstrips at Coldfoot, Wiseman, Happy Valley, and Galbraith Lake, and from many more backcountry tundra and gravel bar airstrips. From the Dalton you can line up caribou and sheep-hunting trips far into the Brooks Range or up the Ivishak River. Grayling and Arctic char fishing in the Iktilik and Toolik can be world class.

We’d scheduled a four-day raft trip down the Canning River, a waterway that forms the western border of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge about 65 miles from the road. After we’d spent two hours winnowing our small mountain of gear into a slightly smaller mountain, our pilot, Tom Johnston, walked up. “Going in the canyon, 900 pounds of bodies and bags is pushing it,” he grumbled. “It’s a tight squeeze out of there. Not much margin for error. I’d say 800 pounds to get out is the limit.”

“So,” Wood said, grinning, “as long as we eat all our food, drink all our beer, and shoot all our shells—we’re perfect!” I stifled a laugh at the scowl I could feel coming from behind the pilot’s glasses. We yanked out a few token items and hid car keys under rocks. Fifteen minutes later we were in the Cessna, with our faces smashed against the glass.

We were ready to slip the leash of the Dalton Highway. We’d started to chafe against the strictures of doing it all: drive and camp and hunt and fish and gawk and drive some more. Sometimes the best place a road trip can take you is to some place far off the road. Now I watched the plane’s shadow below, slipping across the tundra. Somewhere in the mountains ahead was stashed a deflated raft, a jumble of oar frame pipe, and a can of stove fuel. On a piece of paper Wood had scribbled the coordinates of a shelf of tundra for a pickup. We had four days to connect the dots. The char run should be heating up. The ptarmigan should be moving down. We were slightly past the halfway mark to Deadhorse, but the trip suddenly felt as if it were just beginning.

To be continued… If you want to check out part two of “The Last Wild Road,” you’ll have to read it in Nickens’ latest book, The Last Wild Road: Adventures and Essays of a Sporting Life

. You can purchase the collection online or wherever books are sold.