W.C. Fields said, “I never met a drink I didn’t like.” Will Rogers said the same thing about men. I say the same thing about dogs. The way I feel, God proved His love of man when He gave him a dog.

I’ve been spun around by my fellow man, forsaken by loved ones, used and discarded by my friends. Man has a way of playing a game called “You play ball with me and I’ll ram the bat up your left nostril.” I’ve never met a dog similarly disposed.

I’ve walked cross-country in deep snow–late at night–and had the companionship of a dog that I didn’t need to ask to come along.

I’ve sat alone in a sad house and cursed my fortune while the dog curled at my feet had a faith in tomorrow I could not find.

I’ve been hours late getting out a dog’s feed pan and never heard a complaint.

I’ve yelled in rage to clear a room of man and beast only to see a few minutes later one black nose and two bright eyes poke around the doorjamb to scent the spell of the room. I but shifted in my chair and the rascal was in my lap. The men who cleared the room? They may never come back.

I’ve picked up dogs with broken bones and taken them to a vet. No pain could make a dog cry out to his benefactor.

I’ve seen children calmed at night with a dog on their pillow. There could be no better pacifier, no finer protector. I might sleep through whatever befell the child, or shy from an intruder. The dog would do neither.

I’ve seen dogs break ice to retrieve a duck, stand on point with a thorn in the pad, go down a 70 percent grade to corral sheep, chase a car cross-town to be part of a family outing, sniff out a warehouse while policemen crouched outside with pistols drawn, lick a sick man’s feet, kiss a crying child’s cheek, stare beseechingly at a mother’s worried face, raise an arm of a dead-tired man who’d worked too hard to make ends meet.

I’ve seen men bury their dogs and not be able to stand up to leave the grave. And I’ve seldom known a man to mention a dog’s parting.

Last year most of us read in the newspaper about a woman who died and left $14 million to her 150 dogs.

I can hear ’em now. “That’s stupid,” the disgruntled said. “Lots of people could have put that money to good use.” And likely, among the group of worthy recipients would be–themselves.

But I ask the critics of this woman’s will to consider this:

Remember that time you came by a pup? All the doubts? Puddles on the carpet. Gnawed shoelaces. Milk drips on the kitchen floor. But for reasons of your own the pup moved in anyway.

And how did he come through the door?

Did he say, “Hi” so you could understand? I mean, was he fluent in the American language? Did he come bearing gifts? It’s always good to see those types. Did he represent a social coup? Had he done things? Been places? No?

Well, if he didn’t have any of these human attributes, then surely he was pedigreed; they’re worth money, you know. Oh, you say you gave $2 for him at the dog pound. Well, was he pretty to look at, then? “No, kind of rangy,” you say, “and wobble-kneed and pinched-nosed.” Well then was he strong or fearless? Could he do some work, help protect the place? What’s that? “How strong and fearless can a pup be at ten weeks?” I see your point.

Then let’s face it. That dog came into your home absolutely worthless and a total foreigner. I ask you, how many of those have you taken in lately?

And then when this improbable guest got through the door, what did he do? I see. He puddled on the carpet, gnawed shoestrings, dripped milk.

So you threw him out, right?

Nope, wrong.

Why was this?

Well, when that dog came through the door he had three things going for him; a wagging tail, a rough, wet tongue; and an eagerness to say hello to everyone he met.

It was like just meeting you made his day. He quivered with excitement. Rolled over in submission. Nuzzled up so’s the warmth of his body came soothing to your heart through the skin of your ankle. So you picked him up. that’s the way with love. It’s contagious.

And you stood there holding this pup close to your cheek, smelling that last-night’s-ice-cream-carton-smell of him, your fingers sunken into his soft belly, woven through his silken fur, when across your face goes that rough, wet tongue.

What you had in your hands was absolute, non-diluted, ever-growing, non-demanding, can’t-live-without-you, take-me-wherever-you-go, hurry-back-when-you-leave love.

And I ask you this question:

Whom do you have in mind–like this–to leave money to?

But, most of us outlive our dogs, God giving them about 12 years and us close to 70. So, money’s not the legacy, it’s memories.

How many of us go in memory now where in step we went before: toe-to-tail to freedom’s call, the call of gentle wildness, us out walking with our dog?

Whenever I think this way, I always remember Rene. I trailed that dog so many places. We hunted, sure. But we did so much more. We once looked down a hand-mortared flintstone well together. My voice drummed about in there and Rene tilted his head, cocked his ears. As men are but boys grown tall, Rene was always a puppy.

We poked about in old barns, scurrying rats, making feral cats skitter, spooking great horned owls to wing.

Remember the time I thought I shot him? The flushed bird was far enough ahead when I fired. I didn’t notice the great gash across Rene’s chest ’til later. God, the shock when I did. I dropped the gun, the bird, and both my knees. Sweeping Rene up I raced toward the car and into a strange town to a strange vet.

The man lectured me while he sewed up the dog. Guiltily I endured the rebuke about a city man (but I lived on a farm) shooting his dog. Then, I noticed, there were strange perpendicular rips in the skin. That’s it! Rene hit a barbwire fence concealed in the tall grass.

I told the vet to go to hell, paid him, picked up my sewed up dog, and cried with joy all the way back home. But then I had to drive back to the field–to get my gun.

Remember? Remember when the dog played ball with me and the boy? I’d pitch, the boy would hit, the dog would field and fetch the ball to the pitcher’s mound and I’d race to first base to tag the boy.

We had to stop that game. Rene turned pro. He started playing so close to the batter’s box to get a jump on the ball that I was afraid he’d get hit with the bat.

And then the day that the boy, the dog, and I were walking out back by the dam. A great bull snake was sunning himself on the concrete shelf. Startled by our arrival, the snake fell into the pond. This dog, Rene–Wasatch Renegade, sire of two field champions–was a Labrador Retriever, and things that splashed were things to fetch. Off the dam Rene leaped, grasping the great snake, making the shore, the snake wrapping itself around Rene’s neck, biting his right cheek. A bite, incidentally, of no consequence.

Rapidly I started walking toward the house. The boy had to sprint to stay beside me. Huffingly he asked, “Why are we going so fast, daddy? Why, daddy?”

“I’ve got to go to the toilet,” I admitted to the lad.

Inside the house, looking out the kitchen window at the Lab holding the great bull snake, I lectured the lad, strongly, “Don’t ever be afraid of snakes, son.”

But Rene with the laughing eyes, and his way of walking on his hind legs to better look me square in the face, and the ever-waving flag of his tail, and the low guttural whine he’d make when he was trying to tell me something–Rene died. And then I carried him the last time. Carried him and buried him. Mixed prairie grass grows on his grave so one can’t recognize the place. But I do.

I go in memory now where in step I went before. They are strong, sure steps.

And I do not walk alone.

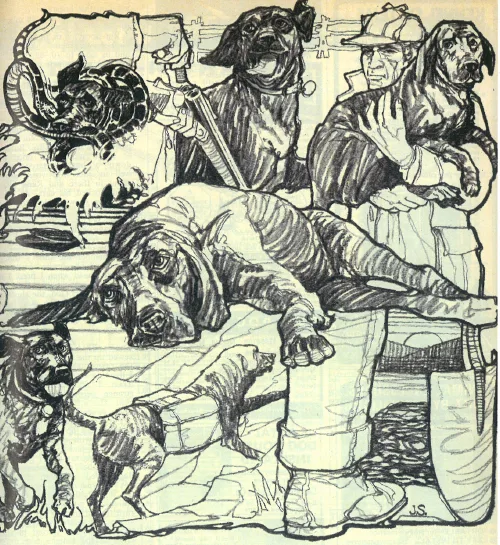

All men who are dog men walk a similar trail. The butterball pup angling off to one side, or the seasoned field worker hired on for the gun and not his gut, or the gimpy, stoved-up senior canine citizen who can’t hear, can’t see, can’t run–they all walk to side at one time or another in a dog man’s life. But the memory companions are set down front and back, absent in presence but not in mind. They are so often the reason the dog man chooses this spot in the marsh for his blind, or goes out of his way in the field to check that thicket, or hole by the cottonwood out back. Some dog, some time, showed the dog man this was where the action is, this is where we harvest.

So, Rene trails with me evermore. And other dogs will join him. Can you imagine the string I’ll put down when I’m old? But I know one thing–the string could be no match for yours. We’re all like that about our dogs . . . and our memories.

A new memory coming for me will be named Pepe. He’s an old dog, Pepe. Peppy no longer is he.

For reasons of sentiment I take Pepe with me to the fields–though I must dally a great deal to wait him out. Pepe walks at heel, reluctant to strike out and sniff.

In man years Pepe (AFC Renegade Pepe) is 88. He’s arthritic with eyes that are pop bottle opaque. Pepe wheezes a lot as he locomotes, grunts when he scratches. If Walter Brennan had been a dog, I think he’d have been a lot like Pepe.

Pepe’s young kennel mate is a dog named Scoop. Scooper he is. Taking long draws on the wind, casting himself in big loops, scooping up all feather that’s idling in grass clump or thicket.

Scoop moves like John Wayne did when John was younger–or Robert Mitchum. Like his hips were double-jointed. It’s a swagger, really. The swagger of competence. Scoop is 42.

I’ve learned a lot about life from Scoop and Pepe. Pepe likes to hold up and lounge under a tree, thinking long deep thoughts.

Scoop has no patience for that. “Let’s activate, not meditate,” says he. “What’s over the next hill, or in the gully by the dump, or the plum thicket by the pond?”

But I remember when Pepe, too, was a seeker. No idler under trees, then. Off and running he was. As a hunting companion and a field champion–the only work he knew–he was one of the best.

What if I’d forsaken Pepe in his old age. Let’s say I decreed that since Pepe could no longer work, he no longer had value. I could have put Pepe to sleep. Or if I kept him on I could have been exasperating. Yelling things like, “Can’t you do anything to earn your keep?” Or I could have given Pepe to some farmer who wanted a dog to ride in the bed of his pickup truck.

But I remembered the past and chose to meet my obligations.

I said, “Pepe, old boy, you excused me so much when you were bringing me along. And so doing, you taught me love and tolerance and humility. All the while, mind you, you were doing your job.

Yes, that’s what I said. Said it to a dog.

Man first domesticated dogs to work. Only later, through the work association, did companionship arise to earn his title: “Man’s best friend.”

Why, the Pawnee Indians were so dog-work oriented that upon first seeing a horse they dubbed it “Super Dog.” And they reckoned the time to go hunting–since the dogs dragged the travois–by the appearance of what they called the “Two Hunting Dog Stars” in the northwest.

But modern man, who’d cut himself off from nature, and the nature of beasts, seems incapable of truly understanding the real world and its real occupants. Such people pose their children with park bears. Working a dog to them is inhumane, a sort of barbaric outcropping of anyone who’d put a dog to the yoke.

So I should have anticipated the comments overheard on the trail the other day when one of my Labs and I–each with backpacks–climbed up, over, and down the Continental Divide.

I’ve lived close to this dog for seven years. I can honestly say I’ve never seen him happier. He fairly laughed on that trail. The pack? He didn’t even know he had it on–except when his saddlebags got wedged in the rocks and I had to come grapple him through.

But the little-old-lady comments of passersby were: “Isn’t that too heavy for that dog? Aren’t those straps choking him? What’s the matter, can’t carry the gear, yourself? What’d you give him, the heavy items? Boy, I’ll bet he’ll be glad to get out of that.”

Now, these were comments from those day hikers, summer strollers, those who mince-footed up the gradual, smooth-worn east slope of Pawnee Pass, some 30 miles northwest of Boulder, Colorado.

Dropping over the Divide and coming down a four-to-one grade, leaving behind forest foreigners, the comments changed to: “That’s really wonderful. Where could I get a pack like that? He’s really having fun, isn’t he? Do you think I could train my dog to do that?”

The west-slope climbers were people who know enough to hazard the grade, who desired to escape the human condition, who sensed the natural order of the universe: that man and beast alike were put here to work.

It was these west-slope naturalists who petted the dog, instead of scolding the master. It was west-slope people who invited the dog to dinner. Incidentally, never once did the do-gooders on the east slope reach out to console the dog. They just gave lip service, not a helping hand.

Modern man, you bewilder me. You bewilder me when you don’t know the nature of things. Like the ad I saw the other day–a rubber suit for retrievers. So the dog won’t get wet if it’s raining.

Just because man no longer understands his place in the universe, don’t let him assume God’s creatures have become equally confused and trivial.

In this department, we won’t.