IT’S MORNING at Kooyooe Pa’a Panunadu, or Pyramid Lake, in Nevada, and I’m fly fishing for the biggest cutthroat trout in the world. It’s my first time at the lake, and I’m here with Autumn Harry, the first Paiute woman fly-fishing guide in its history.

The pressure is on. The anglers down the beach just doubled up. I’ve yet to get bit, and my window of opportunity is closing quickly. On the other side of the lake, the sun is beginning to crest a series of rugged high-desert mountains. According to Harry, direct sunlight kills the fishing. On a clear day like today, most fish are caught at dawn and dusk, and we’re not planning to fish this evening.

I lift the two-handed switch-rod handle up by my head and launch my floating line forward. I’m still learning how to cast this rod and the motion is awkward, but I manage to get my indicator rig out to where the rocky shoreline drops off into deep turquoise, where trout are known to cruise.

“I’ve got a good feeling,” says Harry from a tufa rock next to me. “It’s going to happen soon. I just know it.”

I strip in the slack, point my rod at the cork, twitch it once, and watch it bob in the chop. Any second, a 20-pound Lahontan cutthroat trout could make it drop.

An Ancient Remnant

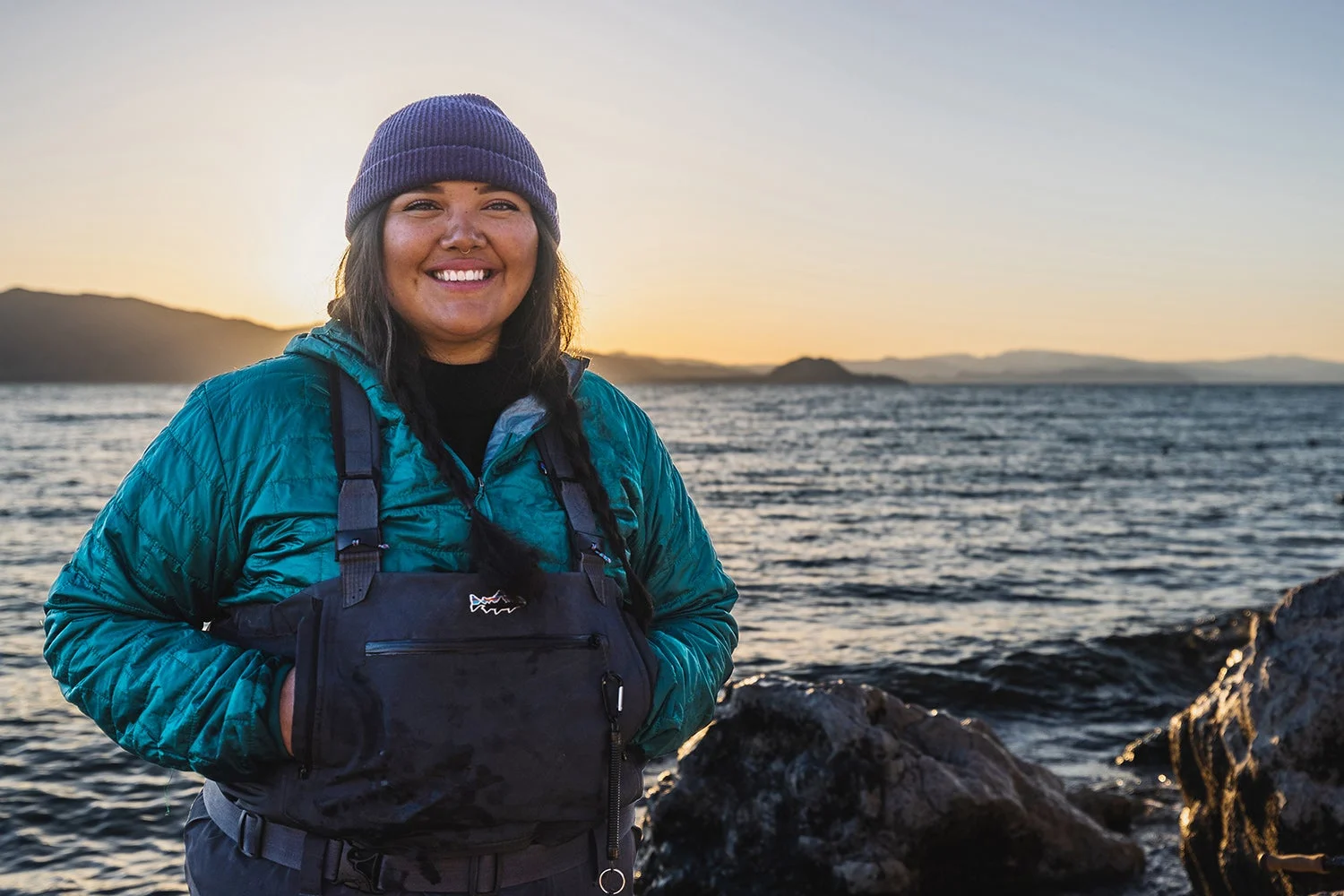

I’d met Harry at the lake early that morning. After a short drive down a rough dirt road, I found her rigging up at her old white Chevy Silverado. She’s nearly 6 feet tall and is wearing a silver nose ring, a beanie, a puffy jacket, and Patagonia waders.

We could still see the stars, and the headlamps of anglers stretched in a line along the shore’s dark outcroppings. It’s mid-March, prime time for the lake’s fly-fishing season. In warmer months, the trout dive deep, but when it’s cold, they’re within range of shore anglers.

Harry and I picked our way down to a small cove surrounded by tufa, a pale, porous limestone formed in alkaline water. The wind had yet to pick up and the water shimmered. It struck me as more than a little improbable, on such a vast body of water, that a trout would happen upon the two tiny midges Harry had tied 8 feet beneath my strike indicator.

At Pyramid Lake’s most popular beaches, anglers often jockey for the hottest fishing spots. Ryan Cleek

But Harry, who is Numu, or Paiute, on her father’s side and Diné, or Navajo, on her mother’s, knows the lake well. I wanted to fish with her because I believed she would help me catch my first Lahontan cutthroat trout (LCT) and because I wanted to know more about her connection to the lake as a member of the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe—a group that has fished here since time immemorial.

Kooyooe Pa’a Panunadu was once part of Lake Lahontan, a glacial lake that spanned most of the Great Basin. As the lake dried up, it left smaller bodies of water behind. Kooyooe Pa’a Panunadu is its biggest remnant. At 112,000 acres, it’s roughly the size of present-day Lake Tahoe.

“The lake is so beautiful,” Harry says. “Paiute people like me have a direct connection to it. I often think about how my ancestors endured so much so that we can be here. My appreciation grows when I think about the history.”

Harry’s ancestors called themselves the Kooyooe Tukadu, which translates as Cui-ui Eaters. Cui-ui are suckerfish native to the lake. Historically, the Kooyooe Tukadu were rich in fish. They traded trout and cui-ui with the first white people who ventured to the lake, led by John C. Fremont in 1844.

Fremont dubbed the water body “Pyramid Lake” for an outcropping that reminded him of the pyramids of Egypt. His group of explorers opened the door to a massive influx of European settlers into northwestern Nevada. In the centuries that followed, the Kooyooe Tukadu worked to maintain their way of life while adapting to the changing world around them.

Then the fish began to disappear.

In the late 19th century, settlers began commercially harvesting the lake’s trout. For a while, the fish held on. Then, in 1905, Derby Dam was constructed upstream to divert water for agriculture and provide electrical power for nearby Reno. It blocked the native cutthroats from reaching their spawning grounds and quickly dropped the level of the lake by 80 feet.

“That was a huge theft of water,” says Harry. “I’ll always be upset about that. Indigenous people were ignored at that time. They weren’t involved in the process of developing a dam that would impact the fish and the community.”

Unable to spawn and without competition from new generations of fish, the lake’s remaining trout grew bigger than ever. In 1925, John Skimmerhorn, a Paiute man, caught a 41-pound cutthroat trout, which still stands as the world record for the species. But it was one of the last of its kind. The dam proved to be a death knell, and by the early 1940s, federal biologists believed LCT to be extirpated from the lake entirely. If not for the work of Harry and her predecessors, it could still be that way.

Long Recovery

Before we started fishing, Harry gave me the rundown on roll casting. With the 11-foot 7-weight switch rod, it’s halfway between a standard one-handed roll cast and a true spey cast. The method allows you to shoot your line through the lake’s typically windy conditions without backcasting. Harry demonstrated by raising the rod slowly, letting the line on the surface load it, and then smoothly swinging the rod forward, launching the line out in a tight arc.

She made catching a fish look natural too, when minutes into the morning she deftly set the hook on a big fish. “Got one,” she said nonchalantly as I stumbled to shore to grab the net. After landing the trout, Harry smiled and held it for a quick photo. It was a girthy cutthroat with a bullish head and bulging belly. In several weeks, it would likely swim to an artificial spawning channel constructed several miles down the shore to be manually spawned—an operation that is the cornerstone of the tribe’s decades-long efforts to recover the fishery.

Harry lands the first fish of the day—a beautifully speckled Lahontan cutthroat. Ryan Cleek

When the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe launched Pyramid Lake Fisheries, in 1974, it took fish from nearby Summit Lake, home to the Summit Lake Paiute Tribe of northwest Nevada, and introduced them to Pyramid Lake, then bolstered the effort with an extensive spawning program.

Harry’s mother, Beverly, worked for the Fisheries for years, and so did Harry, who has served as both a creel census worker and fish culturist. She’s been participating in the spawning days—usually, there are five each spring—since 2014.

“I’m no longer working with the Fisheries, but I still make it a point to volunteer during the spawn,” says Harry. “It’s fun and rewarding. We’re creating life. To see the big fish swimming up the spawning channel is a way to visualize success—that these fish are doing well.”

During my trip, Harry and I visited Fisheries headquarters, where the spring spawn would soon take place. The facility’s spawning channel is in essence an artificial river—a concrete trough that reaches from the lakeshore up to a series of circular pools holding small trout, whose pheromones are meant to attract spawning fish. Staff would soon pump water from the depths of the lake up to the top of the channel and run it down the sloped concrete to mimic a natural current. Spawning fish will swim up the channel and be trapped, and then staff and volunteers will harvest their eggs and milt to use at a nearby hatchery.

Headquarters is a single-story brick building adjacent to the spawning channel—a nondescript building for the site of one of America’s greatest fishery conservation success stories. There, we met Mervin Wright, the current executive director of Pyramid Lake Fisheries, who, along with Harry’s late father, Norman, a former tribal chairman, played a key role in the fishery’s recovery. Over the past 50 years, the two men used negotiations and lawsuits to secure enough water for the lake, and they fought to limit the amount of effluent—in this case, sanitized human waste—and PFAS that enter the lake.

In that time, the fish inhabiting these waters have changed some, too. In the late 1970s, a trout found in a small stream in northwest Nevada was identified as Lahontan cutthroat. Later genetic research showed that the fish, from what’s now known as the Pilot Peak Strain, was closely related to the original Lahontan cutthroat trout in Pyramid Lake. The fish had likely been relocated to northwest Nevada in the early 1900s.

At the Fisheries headquarters, Harry points out an old photo of herself with a massive LCT she measured during a stint as a creel-census worker. Ryan Cleek

In 2006, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) partnered with Pyramid Lake Fisheries to stock the Pilot Peak strain in Pyramid Lake—and the fish grew even larger than those sourced from Summit Lake. The effort caused some tension initially, as some tribal officials felt that their efforts with the Summit strain were underappreciated. But today, both strains of LCT coexist and thrive in the lake. According to Harry, the large trout have sparked a surge of interest in the lake—and pride in many local tribal members.

“All these fish belong to the lake,” explains Wright. “We belong to the lake. We’re just taking care of the fish. As long as we keep that up front, we’re going to be OK.”

Family Current

On the water, Harry is quick to smile and never seems to get frustrated, no matter how many times I get my rig tangled with poor roll casts. It’s in the 40s and windy—not tropical by any means—but a pleasant day for Pyramid Lake, where, unfortunately, the fish are known to bite best when it’s nasty out.

We cast and wait, cast and wait. If I were fishing alone, I’d fuss with my flies, perhaps change the depth of them. But Harry is confident in the setup. She grew up in Nixon, a town nestled along the southern tip of the lake, next to the mouth of the Truckee River. Home to around 300 people, it’s the community center of the reservation. Harry’s childhood home is on the edge of the town, surrounded by a sea of sagebrush. From her back door, she could often spot pronghorns ranging the folds of her ceremonial mountain. At night, she fell asleep to the cries of coyotes.

Her father was a spin fisherman, and the two of them spent countless hours throwing spoons and spinners for big cutthroat trout. When Harry caught her first cutthroat, she gave it to her grandmother, Charlotte. “It’s a tradition in the tribe. When we catch a fish, it’s always good to give it to somebody. It goes back to reciprocity. My first fish I gave to my grandma. She gave me life. And she loved our fish.”

Harry peruses fly patterns before dawn over the tailgate of her truck. Most of her fly boxes were filled with midges and leeches. Ryan Cleek

Initially, Harry didn’t learn how to fly fish—which seemed inaccessible and intimidating to her. But then, in 2018, a local guide named Casey Anderson invited her out. Most of the guides at Pyramid Lake winter in trailers at the small outpost of Sutcliffe. They live and guide elsewhere during the summer, when Pyramid Lake’s season for LCT is closed. The guides come to know the lake and its fish well but have limited connections to the broader community.

Anderson wanted to change that. In Harry, he found a natural fit. At the time, she was already well known in the community for fishing and organizing around water justice and Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and People. Anderson lent her gear and started showing her the ropes. She got skunked the first time out but not the second. “When I caught my first fish on the fly, I was hooked,” she says. “I said thank you to the fish, then released it back into the lake.”

In 2020, the pandemic forced the tribe to close the lake to nonresidents. Harry was left to fly fish on her own, but with time on her hands, she perfected her fly-fishing knots, improved her cast, and started catching more fish, while her dad cheered her on.

“To catch the fish and connect with them is more than special. It’s like medicine.”

—Autumn Harry

She and her father filleted the catches and donated them to local tribal members, as the pandemic limited the availability of store-bought fish and poultry. Unknowingly, Harry was also enjoying some of her last moments with her father. In August 2020, Norman passed away from a heart attack.

The loss hit Harry hard. She took a year off graduate school, where she’s a master’s candidate in geography, to mourn and support her mom. When she resumed her studies, her grad-school funding ran out. She decided to find another way to support herself—by becoming an independent fly-fishing guide.

“My dad and I wanted to do this kind of work together,” she says. “He was only 65 when he passed. Our big plan was to start a business together when he retired. He would lead cultural tours, and I would lead fishing trips. I know that he would be proud of the work that I’m doing now.” In her father’s memory, Harry designed a T-shirt featuring one of his favorite sayings: What is good for the fish, is good for the people. “He loved to share what he knew,” she says. “Now, that’s my role as a guide.”

Keepers

As the sun hits the surface of the lake, my stomach sinks and I start fidgeting. I’d worn multiple layers beneath my waders, but the coldness of the water inevitably sets in. I glance down the beach whenever another angler hooks up. Harry reminds me to keep my eye on the cork.

Unlike most fly-fishing guides, Harry tells me I have the option to creel a trout as long as it’s legal under the lake’s strict regulations. She encourages her clients to share the fresh meat with elder family members or community members in need. “In fly fishing, there’s often an attitude that people look down on keeping fish. I have to remind people that we’re the Kooyooe Tukadu—the Cui-ui Eaters,” she says. “We’re fish eaters. It’s in our name. It’s how our people survived. It’s important for anglers to think about that and not look down on it.”

Becoming the lake’s first female Indigenous fly guide wasn’t easy. Harry faced tension from other guides, some of whom questioned her experience. But she was motivated to make fishing more accessible, particularly to women and minorities. She says she makes progress with every guiding trip, speaking engagement, and community event, though she still encounters resistance among some members of the greater fishing community.

“I hope to see an increase in tribal guides in the future,” she says. “It’s important for visitors to learn directly from tribal members, who can provide education on how much our people have done to maintain a healthy fishery.”

Harry grew up in Nixon, which is 20 miles down the shore from where we fished. Ryan Cleek

Besides guiding, Harry, along with Jolie Varela of Indigenous Women Hike, has started organizing and running an annual three-and-a-half-day fly-fishing retreat for Paiute women from throughout the Great Basin who are new to the sport. Inspired by other Native organizers, she’s also putting together a gear library to make equipment accessible to tribal members and people who may not be able to afford it. She continues her work as an advocate for clean water and Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and People.

Though Harry is a fly-fishing guide, she still spinfishes and says it will always have a place on the lake, as will creeling fish. She hopes to cultivate an ethic of sharing and respect among visitors that aligns with the Indigenous heritage of the lake.

“Regardless of the fishing method, the act of being out on the water is really special,” she explains. “To catch the fish and connect with them and hold them is more than special. It’s like medicine.”

Hope Rewarded

When it finally comes, the strike is anything but subtle. One second, the orange cork bobs clearly on the surface. The next, it’s gone. I raise my rod, and it goes heavy.

Now I’m really feeling the pressure. I know that shots at these fish are limited—and that if I screw this up, I may not get another. Gripping the line tight with my numb fingers, I strip the fish in as quickly as I can without breaking it off. When Harry nets the trout, I’m flooded with relief and rush to admire my catch. A blush of pink extends the length of the fish, and its flank is freckled with black spots. Pushing 20 inches, it’s a small trout by Pyramid Lake standards, but it’s still one of the biggest cutties I’ve landed—and one of the most meaningful. I let out a quick whoop and high-five Harry. After snapping a few pictures, I release the fish and retreat to a spot on the shore, where I sit until I stop shaking.

It turns out to be my only trout of the day—and the trip. I fish Pyramid Lake hard for two more mornings without another bite, watching the indicator bob in front of stark desert mountains for hours as my toes grow numb in my neoprene waders. I knew going in that fishing here could be punishing but was glad I’d made it count the one time my bobber had jagged. And I was grateful to wet a line in such a legendary place, knowing so much more about it than I would have if I hadn’t fished with Harry.

On the third morning, before I drove home to California, I packed up my gear and made small talk with another guide, who grumbled about the slow fishing. Then I made my way down the rocky beach to Harry, who was with two new clients. She smiled wide and asked me if I’d seen the moon that morning. I had—the rising sun had made it glimmer orange above the dark surface of the lake.

I was struck by Harry’s hopefulness that a fish would bite—which reminded me of her broader hopefulness that the fishery would continue to recover and that fly fishing would become more inclusive. Later that day, she sent me a photo of one of the most beautiful trout I’ve ever seen. Already in its spawning colors, its belly was a deep burgundy. It had taken all day, but her hope had proven justified.

_Read more F&S+

stories._