FOR STARTERS, I had to slow everything down. My cast, for sure. I tend to rush through the fundamentals when I get on new water, pushing the rod too hard, not letting the fly line flatten out behind me before starting the forward cast. Tailing Loop City is where that will take you.

A fly cast is like a heart-rate monitor: It can tell you a lot about your state of mind—good or bad. Start the cast too early, and the rod is overhead before it even moves the fly, and you wind up pulling a giant line of slack from the water. Push the rod too firmly, and the rod tip bends too deeply, dragging fly line with it and forming a tailing loop. It’s all right there, writ in the sky overhead. I was rushing the cast. I needed to slow down. And in fly casting, slowing down is actually the first step to getting more stuff done. Or, at least, more of the stuff that matters.

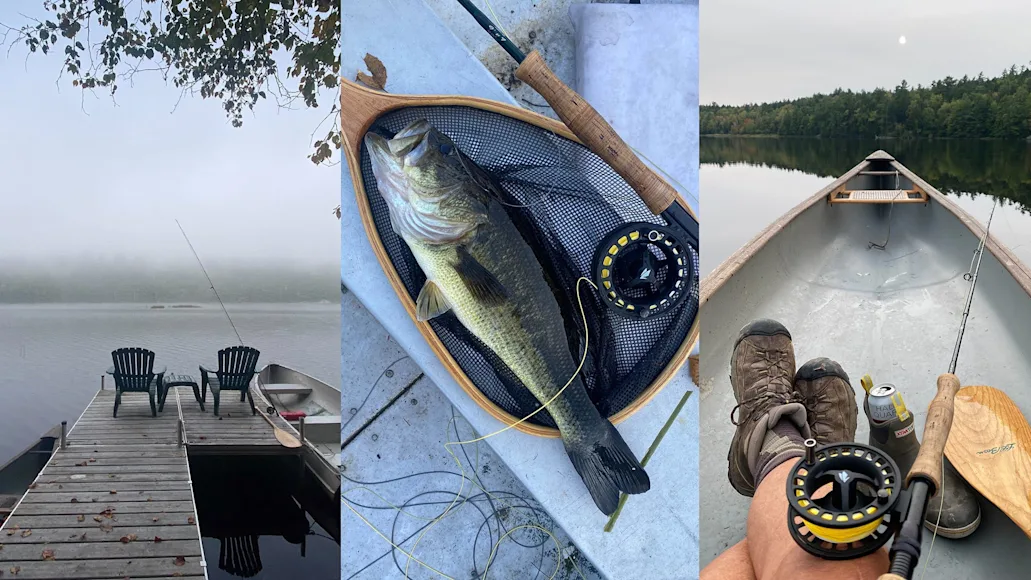

I was in the right place for such a lesson. My buddy Frank bought a pond cabin in Maine 20 years ago. The one-room getaway was built around 1950, and Frank threw out the calendar when he took ownership. Very little inside dates to any era past circa 1960. The cups and plates are vintage enamelware. The pots are old cast iron. There’s a working phonograph. There’s a mounted gray squirrel above the double bed that might predate the Revolutionary War. There’s a fleet of old rods with old Zebco 202s hanging from the rafters. There’s an old poster from a local fur buyer announcing his wish list: I WANT MUSKRATS • EXTRA DARK RED FOXES • COYOTES AND BADGERS.

Outside the cabin was the best find: Stashed under dense firs was a 12-foot aluminum V-hull boat, and clamped to a porch railing was a 1960 Sea King 5-horsepower outboard. I hauled the boat to the water and the motor to the boat. The motor alone must have weighed 4 million pounds. Sea King was the in-store brand of the old Montgomery Ward department store chain. If you’ve never wanted a DeLorean with a flux capacitor, then you probably have never heard of Montgomery Ward. But there was a time when big-box retailers sold their own store brands of outdoor motors, and legacy department stores were just as likely to carry shotguns and rubber worms as cake mixers and bed pillows. My first .22 rifle was a wood-stocked J.C. Higgins Model 29, the store brand of Sears. For years just after I graduated from college, my pal Lee Davis and I ran my duck boat with his old Wizard 9.9-horsepower outboard. Wizard was the store brand from Western Auto.

If I sound old, I’m not. But I can see old from here.

Wild places like this Maine pond chasten me for the lack of balance in my life. When you find yourself in a place ruled by tide, there is plenty of feedback to tell you when you’re moving too fast.

The Sea King coughed on the first pull and started on the second. I took off across the pond, hand on the tiller, a beer propped up in a spare hiking boot. I was straight out of the mid 20th century. I felt a little guilty for wearing a sun hoodie and nylon pants.

It’s a tricky thing, dancing with the past: I’d come to Maine to pare things down to the basics. A little old cabin with my wife. A little old boat. Spotty cell service and a news blackout. Turn back the clock for a bit. I even brought my oldest fly rod, a Winston 7-weight that I’ve had for some 25 years. Frank told me to be prepared, that his cabin was moored in a different century. To be honest, tossing out an anchor in an ageless place seemed like good medicine.

Tick, Tock…

For most of us, time moves too quickly and comes with so many demands that it seems impossible to leave our responsibilities behind when we pick up a rod or gun. We try to squeeze a day in the woods into a week that’s already stuffed to the brim—or cram a few hours on the water into a day so packed with deadlines and expectations that we can’t fully enjoy playing hooky. It’s ridiculous how often I rush to the deer woods an hour after I’d hoped to leave the office, or blast out of the house on the way to the duck swamp with my backpack a mess and my mind a train wreck of things undone and guilt for leaving the office in the first place.

Wild places like this Maine pond chasten me for the lack of balance in my life. When you find yourself in a place ruled by tides or paced by the sun’s arc and little more, there is plenty of feedback to tell you when you’re moving too fast, or when your head’s not in the game. The deer that canters off, white tail at half-mast, aware but not alarmed? That happens when my mind has wandered back to some half-finished email and I fail to watch where my boots are going. The missed strike on the dry fly, the gobbler that seemed to appear out of nowhere—it feels like these things happen most frequently when I’m not fully present.

On the Maine pond, I do my best to take my time, because it’s my time, after all—a distinction I tend to forget. I had putt-putted the little aluminum V-hull to the back of the pond and took a moment just to look around. The lily pads looked perfectly fishy up against the pickerelweed, which stuck out of the pond’s clear black water in front of the mossy boulder that was beneath the evergreens and the maples turning red and the blue sky and the white birches. If I were a Maine pond bass, I’d be hunkered down right there, in the pickerelweed, waiting on a smelt to meander by.

I cast and watch my fly line unfurl against the dark timber, a physical expression of how deeply I’m embedded in the world around me. The more I’m in the moment, the tighter the loops become. I see this happening in real time, in the fly line against the dark trees, and it reminds me to slow it down. Feel the line load the rod. Be in the moment.

The bass didn’t want to be in the pond-side salad. He wanted to be out in the open water, and it was only when I took my time and fished the fly all the way to the boat that I found him. He struck hard and ran for a downed tree, and as I turned him with the rod, for a few seconds we could see each other through that clear black water. I swear our eyes locked, and something passed between us that I couldn’t really define.

It’s crazy that I have to learn the same lesson over and over again: Let it all happen in its own sweet time. When I released the fish and watched it fin slowly out of sight in the deep water under the boat, it occurred to me that every moment that passes—every cast, every fish, every sunrise—each of those moments is suddenly, viscerally here at hand, and then suddenly, irretrievably, gone. Every minute and every hour is like that. Every moment that passes has passed forever: It is just as gone as the day the Sea King was made.

Time, an old man once told me, is the ultimate equalizer. All of us—teacher or subject, old or young—have the same amount: All there is.

I rubbed the fish slime off my hands and picked up the rod. When I backcast, I felt the rod load behind me, and I gave it another beat before sending the fly forward toward whatever might happen. I watched the loop unroll. A tight one. Nice. It was about time.

_Read more F&S+

stories._