At the conclusion of a recent presentation by Save Wild Trout on their monitoring efforts in Montana's Jefferson River Basin, the mood in the community room at Helena’s Lewis and Clark Public Library was equal parts somber and urgent. Roughly 100 miles to the southwest, four of the rivers that make up the basin—the Beaverhead, the Ruby, the Big Hole, and the Jefferson—were facing another summer of high temperatures, early algae blooms, and other water quality problems.

Decades of anecdotal evidence and intermittent chunks of hard data show that the ecological wellbeing of the Jefferson River Basin is degrading in a variety of ways, according to members of Save Wild Trout. Fly guides report scarcer bug hatches every year. The density of nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus are consistently above threshold for healthy trout populations. So is water temperature; parts of these rivers reach above 80 degrees Fahrenheit by the end of the summer. Dissolved oxygen—the stuff fish breath—is down.

The impacts on the ground hit deep for a tourism economy centered around ample fly fishing opportunities. Similarly, Beaverhead County’s hefty population of ranchers and farmers rely on the Jefferson River Basin for irrigation, especially amid lingering drought conditions and soils with very low moisture content. Put simply, Beaverhead County runs on cold, clean, abundant water, and their supply is getting low. But how low? And why?

Searching for Culprits

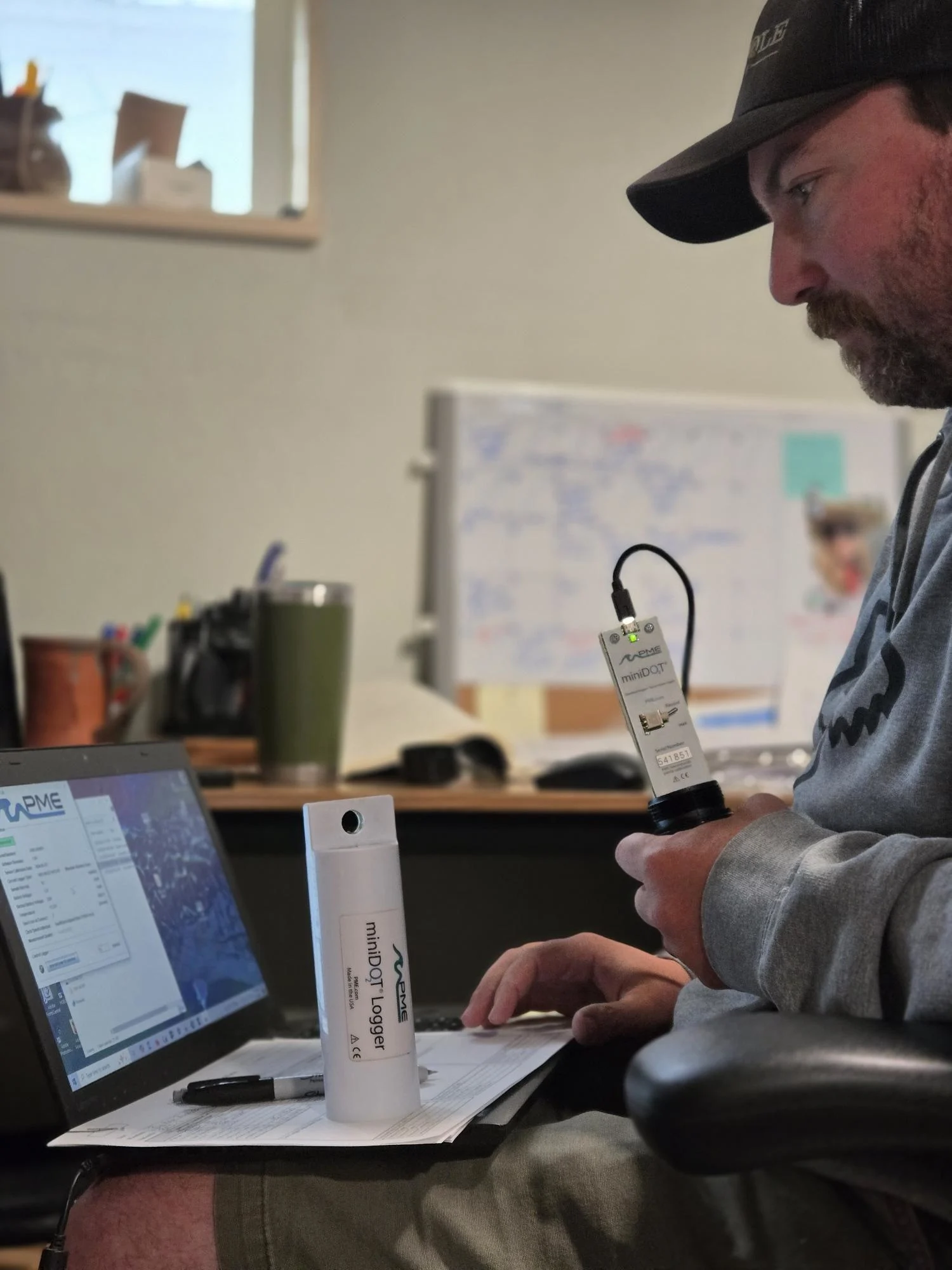

These questions drove member organizations of the SWT campaign—members like the Big Hole River Foundation and Upper Missouri Waterkeeper—to initiate a two-year research project in 2023. They used submerged data loggers, boat surveys, water sampling, and even helicopter-mounted infrared camera flyovers to collect a pile of data on different water quality metrics. The goal was simple: First, fill the gaps in data in a way that supports and complements state agency efforts to manage the basin. Then, start looking for the smoking guns.

The group, which partnered with KV2 Consulting, compiled the results of the study into a report they released to the public on July 14, coinciding with the meeting in Helena. It’s practically impossible to draw catch-all conclusions about water quality for the entire lengths of four separate rivers, KV2 environmental engineer and water quality specialist Dr. Kyle Flynn tells Field & Stream. But overall, he says, the basin is enduring a rough few years.

“A lot of our data was from 2024, which was a particularly low flow year,” Flynn says. "But in that year, at least three of the four rivers, from a thermal and dissolved oxygen perspective, did not look great. Downstream of reservoirs, things aren’t bad, but as we move away from that cold water source, you start seeing negative impacts. The Beaverhead behaves that way.”

The Ruby, Flynn continues, had the best thermal and oxygen data of the four different river systems, even though it did struggle with sedimentation. The Big Hole was in decent shape in some places and rough shape in others. And the Jefferson was overall quite warm and struggled with low oxygen, which Flynn says shouldn’t come as a news flash to anyone familiar with it.

“I don’t know if I want to give [the Jefferson Basin] an overall grade,” Flynn continues. “It’s probably too early for that. But in the first year of real detailed monitoring, things didn’t look great.”

"The Cost of Doing Science"

Even though the results are troubling, the data collection itself is a huge win for the coalition. Citizen science initiatives like this one pick up slack as the Trump administration divests from both its own research institutions and its grantmaking programs for state agencies. For example, the Environmental Protection Agency under administrator Lee Zeldin still stands to lose its entire research arm as part of an agency reorganization plan.

A total of $2.12 billion in EPA funding—or a 23 percent year-over-year budget cut—is currently on the chopping block as part of the “Big Beautiful Bill.” Specifically, the Clean Water State Revolving Funds, which the federal government allocates to all 50 states and Puerto Rico for things like non-point source pollution control and runoff mitigation, is facing a 25 percent cut. (These are distinct from Drinking Water State Revolving Funds, which also face a 19 percent cut.)

Instead, SWT relies on partners from the private sector and donating members to fund their work. And that work isn’t cheap, says Brian Wheeler, director of the Big Hole River Foundation and SWT researcher.

“As it turns out, all this equipment is quite expensive,” Wheeler says. “The handheld meter that collects these parameters costs nine or ten thousand dollars. Then, you’re talking twenty thousand dollars for lab analysis of water samples. When we collect bugs in the fall, that’s another forty thousand dollars or so for lab analysis, not to say anything for the mileage or time to collect those samples.”

To raise money for all these costs associated with crucial data collection, Wheeler says SWT and other groups have “gone through the wringer.” He explains that SWT must collect data in a highly specialized manner to ensure it’s useful to the Montana Department of Environmental Quality. Both MDEQ and Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks conduct their own research in the Jefferson River Basin, but they’re limited in what they can accomplish across the whole Big Sky State.

“We don’t just hold onto this information we’re collecting from our watersheds. We’re providing it to the state of Montana and uploading it to the state water quality portal,” Wheeler says. “Therefore we have to make sure it’s well-documented … It’s not particularly difficult work, but it’s extremely particular in how it needs to be done to ensure that our data is credible.”

SWT’s work doesn’t stop with research, though. In February, the Big Hole River Foundation and Upper Missouri Waterkeeper petitioned MDEQ to apply an impairment designation to the Big Hole River, due to exceedingly high levels of nutrient pollution. MDEQ denied the petition, and in May, Waterkeeper sued.

Read Next: Trump Administration to Revoke Roadless Rule Protections on 58 Million Acres of Public Land

“We in Montana have a constitutional right to a clean and healthful environment,” Waterkeeper executive director Guy Alsentzer says. “That means we have an ecological life support system, that there is an intrinsic value in our rivers as well as a utilitarian one. But we can’t manage what we can’t measure. And if we don’t understand what the baseline of health is for our river systems, we can’t understand what they can and can’t support.”