I EXPECTED THE CABIN belonging to one of the country’s most famous fly-fishing families to be more difficult to find, as if it should be cloaked in mystique instead of nestled among giant Western larch trees along the western shore of Seeley Lake in northwest Montana. Thanks to Norman Maclean, who wrote A River Runs Through It in 1976, fly fishing is synonymous with Montana. Although Norman passed away more than 30 years ago, the simple, hand-built log cabin remains in the family. His son, John N. Maclean

, now the family patriarch, continues the family tradition of writing, fishing, and a deep-abiding love for Montana.

I’ve driven 90 minutes from my home in Kalispell to the cabin in Seeley Lake where Maclean is spending his fall, doing what he’s often done since a boy: fishing and using the storied space for inspiration for his own growing volume of books he’s written. It’s a dreary, cold, and rainy fall day and Maclean, dressed in blue jeans, worn hiking boots, and a quilted fleece pullover, welcomes me in from the rain.

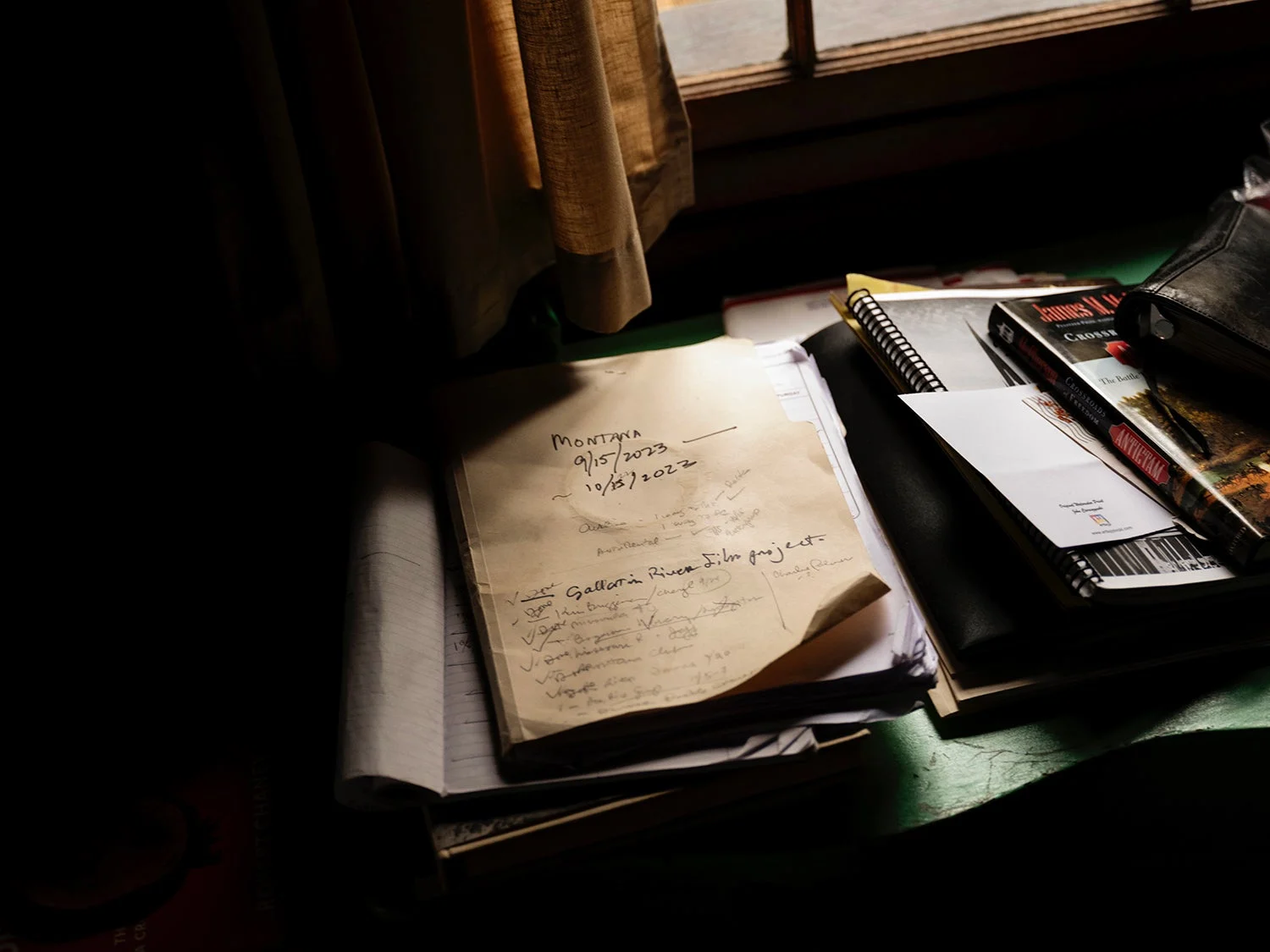

John N. Maclean looks over the draft of a story at his family’s cabin in Montana. Rebecca Stumpf

Built starting in 1921 by his grandfather, the Reverend John Maclean, the cabin has changed little through the generations. Maclean instructs me to sit in an old rocking chair placed in front of the wood stove in the tidy living room, where there are also two twin beds and a small writing desk. A steady fire burns as Maclean takes a seat across from me in a leather chair, his back to the desk placed against a paned glass window. I take in the surroundings: Fishing vests and waders drape from hooks on the oiled logs, and around the walls hang two deer mounts and various black-and-white photographs of the family. It feels like hallowed ground. Here is where his father worked on his legendary novella, the culmination of his dream of being a writer. It’s the place Maclean returns to at least twice a year from his home in Washington D.C., typically in the spring and fall, when the area and its rivers are much less crowded.

A Continental Divide

Maclean, who turned 80 this spring, was born in Chicago in 1943. From a young age, he was keenly aware of how his family was split in spirit between the Midwest and Montana. His parents, Norman and Jessie Burns, were raised in Montana but moved to Chicago in the late 1920s to make their livelihoods. Norman taught English Literature at the University of Chicago, and Jessie worked as the executive secretary for the university’s medical and biological sciences alumni association. During their summer breaks, Maclean’s parents would drive him and his sister, Jean, to Montana.

Maclean goes for a stroll along Seeley Lake. Rebecca Stumpf

For his parents, Chicago represented intellectualism, a culture dramatically different from how they grew up in Montana, Maclean told me. In his firm and exacting voice, he explained that, as a boy, he felt at odds living in a big city compared to summers spent at the cabin and nearby Big Blackfoot River. “We would spend our summers in this Eden, fishing, living close to one of the most beautiful places in the world,” he said. “I remember spending the whole school year at the University of Chicago neighborhood where intellectual life was a pressure cooker.”

For his father, Maclean imagined, the disparate lifestyles between Chicago and Montana were even more pronounced. “Looking back on it,” he said, “I can see that my dad was split in his own way, perhaps even more than I was because he was older, more sophisticated, and had more at stake.”

One way in which the father and son were able to bridge the divide between the Midwest and Montana was through their love of literature, in particular Ernest Hemingway’s short story, “Big Two-Hearted River.” Maclean said his father shared the story with him when he was 13 years old. After reading it, he was able to make sense of this geographic split that also splintered spirit. The appeal of “Big Two-Hearted River” was that, for the first time, the father and son found literature and fly fishing in one contained story. Maclean still remembers how it felt when he first read the story: “I can be in Chicago and move my imagination to a trout stream,” he told me. “I really liked the Nick Adams stories because here’s this Midwestern kid, and he was living this wonderful outdoor life.”

As a Midwestern kid himself, Maclean said he knew exactly what Hemingway was depicting when he placed Nick Adams in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula to fish. Together, Maclean and his dad would discuss the story at length, analyzing the metaphors of the burned-over countryside of Hemingway’s drawn-from-life landscape and what contributed to Nick Adams’ troubled mind.

A small monument to Norman Maclean and his wife, Jessie, is near the family’s cabin. Rebecca Stumpf

Hemingway became Maclean’s favorite author—although he wasn’t a complete fan. He says he favors his short story collections over the novels. Nonetheless, Hemingway became an early influence, especially as Maclean became a journalist after college similar to how the legendary author got his start as a cub reporter. “Big Two-Hearted River” proved to the Macleans that fly fishing could be literature. This idea didn’t fully materialize with the teen at the time, but it was a revelation to Norman, and Maclean noted that the idea that “our sport, fishing, can be high literature” would be a lasting influence.

The Fire Within

“Big-Two Hearted River” was more than a story about a solo fishing trip. The main character, Nick Adams, struggles to land trout. It discussed the effects of a wildfire on a remote landscape and relied upon a lean vocabulary to delve into its character’s mental distress. The elder Maclean wrote about timber, fly fishing, and wildland fires in A River Runs Through It and his posthumously published work of nonfiction, Young Men and Fire. The younger Maclean would go on to spend 30 years as a journalist, the bulk of it as a Washington D.C. correspondent. Like his father, Maclean was pulled toward writing about subjects that Hemingway offered in his seminal short story.

After more than a decade as the diplomatic reporter for the Chicago Tribune, which included filing stories as a member of the “Kissinger Shuttle,” covering the dealings of former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, Maclean left the newspaper business. At age 52, he went West to launch the second phase of his writing career, this time as an investigative writer of deadly wildfires. He drove from his home in D.C. to Colorado to cover the tragedy of the 1994 fire on Storm King Mountain, near Glenwood Springs. The events of the catastrophic South Canyon Fire, which claimed 14 lives, would become his first book, Fire on the Mountain. Published in 1999, the award-winning book carried echoes of his father’s work on Montana’s Mann Gulch Fire in Young Men and Fire, but Maclean was determined that it was possible to write within the same vein as his dad while forging his own path as an author.

Four more books on tragic wildland fires would follow, and Maclean would use the family cabin as a place to conduct his exhaustive field research. The desk that faces the window where Maclean can look out into the woods and the lake, is original to the cabin. It’s handmade but he isn’t certain if his grandfather made it or not. While he finds it easier to write his books from his home in D.C., he sits at the desk to do his “fieldwork,” which involves making transcripts of interviews, fact-checking, and writing drafts. His dad wrote at a different desk, sometimes in front of the fire or during bouts of warm weather, on the porch.

Maclean makes a cast on the Blackfoot River—his family’s home river. Rebecca Stumpf

After Fire on the Mountain, Maclean would continue to write about fire in the American West and the individuals who worked on the fire lines. His acclaimed books would become a critical part of the conversation on fire literature. Also, many firefighting agencies, including the U.S. Forest Service would adopt titles like Fire and Ashes and The Thirtymile Fire as training manuals to help prevent tragedies such as South Canyon from happening again.

Even though Maclean blazed his own path in this second career, he still found himself confronting the ghost of his father and the comparison of his growing body of literature work to Young Men and Fire. It wasn’t easy.

“I had to take on Young Men and Fire and part of A River Runs Through It for a lot of years,” he said. “And I did it. I established a totally independent identity.”

He enjoyed the challenge of writing about each fire and felt confident in his own unique writing voice but over the years, the devastation of reporting on these deadly fire accidents began to take its toll. “All these stories are about worthy young people being burned to death,” he explained, his voice grave. “I had a little case of PTSD.”

What helped him make sense of the tragedy was the same thing that made sense for the character Nick Adams: fishing. Fly fishing, especially on the Big Blackfoot River, restored his spirit.

Returning Home

After more than two decades researching and writing about fire in the West, in his 70s, Maclean’s writing life followed a different tributary.

In 2021, he published his sixth book—a memoir titled, _Home Waters: Chronicle of Family and a River

_. In this award-winning book, he said he aimed to take A River Runs Through It head-on. The memoir unveiled the stories behind the century-long love affair of the Maclean cabin and their home waters, the Big Blackfoot River. Written with great candor and familial affection, Maclean shared the history of how his family related to each other through their connection of a wild trout stream and an old log cabin. He had almost 30 years of material saved, trying for years to write about his early memories of fishing with his father. It took time to develop those stories. Compared to his long career in journalism, writing the family chronicle was a significant shift. “With nonfiction, it takes a lot of discipline,” he said. “You really have to do it straight. When you get into memoir writing, it opens everything up. It was more fun to write, frankly.”

With _Home Waters

_, he was once again prepared to meet criticism or comparison to his father, but the reception has been overwhelmingly positive. The book tells the true stories of the characters behind A River Runs Through It and is also a passionate tribute to the landscape that continues to inspire him. It also reconnected him with Hemingway, and in the book, he shared how influential the famous writer of American letters was to both he and his dad.

A collection of notes and books rests on the desk inside the Maclean’s family cabin. Rebecca Stumpf

After Home Waters, Maclean and his editor, Peter Hubbard, considered a new project that would allow Maclean to explore the connection between Hemingway’s classic “Big Two-Hearted River” and its prevailing power, including inspiring his father to write A River Runs Through It. “Big Two-Hearted River” was now public domain, and Maclean would pen the foreword to the new centennial edition.

In 2022, with the new project on his docket, he revisited “Big Two-Hearted River,”

charting its longstanding influence over him and his dad. He spent much of the year looking through Hemingway archives, early drafts of the short story, and reams of commentary. Part of the experience included an August fishing trip to Seney, Michigan, the story’s setting, and then a residency at the Ernest and Mary Hemingway House in Ketchum, Idaho in the fall. During the residency, when he wasn’t immersed in research or giving a lecture, he had an opportunity to fish the nearby Big Wood River with great success.

Maclean told me how rereading “Big Two-Hearted River” at age 80 felt compared to when he first read it when he was a boy. “The story is almost 100 years old,” he said. “It is so fresh, so good. It was everything I had felt about it the first time I ever read it and more.”

Maclean is happy to reflect upon his long writing career, delving into the nuances and details of what he learned about Hemingway—including how Hemingway saved absolutely everything he wrote—but the significance of the foreword of the standalone edition of “Big Two-Hearted River” is the pinnacle. It is a culmination of a story that forged a bond between father and son, and Maclean is receiving a lot of correspondence and inscription requests from fathers who want to give the book to their sons.

“It’s turning into a big father-son book,” he said. “My dad gave [“Big Two-Hearted River”] to me. There’s a bond between us that lasts to this day. This draws all the way back to when I was a 13-year-old kid. My dad and I wanted to be writers, and we both did it. It took us forever, a whole lifetime. It set us on paths that we would not have followed otherwise. Without “Big Two-Hearted River,” all the books that my dad wrote would have been written differently. Perhaps none of them would have been written.”

For Maclean, sharing a byline with his literary icon feels like both a beginning and an ending—a fulfillment of an enduring influence on one writer’s imagination and the everlasting bond between father and son. Writing the new foreword to “Big Two-Hearted River” is similar to the cabin and the desk, objects transformed into stories that have meant everything to him. “The desk has meant my second and most welcome career as an author of books and other writing about the West,” he said. “It is my reconnection with Montana and the cabin—the places of joy of my youth, and the joy of my father and his father before him.”