_We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn more ›

_

The Frontier West was nothing if not a place of opportunity. It offered an unlimited number of ways to perish including disease (a big favorite), thirst, starvation, weather, livestock, serpents, insanity, and, of course, your fellow man. There was not a lot you could do about anything except the last, and for that the remedy was: Get a gun.

It helped a lot if you kept that gun handy and became proficient with it (though most didn’t, as is the case today). It was hard to keep a rifle close at hand at all times, but a handgun was another matter. And so revolvers became as necessary as saddles, axes, and branding irons.

The four revolvers I’ve picked as the greatest handguns of the Old West were selected not only because they stood out among a mob of competitors, but because they were game changers. Not surprisingly, all happen to be Colts. So what? I could throw in a Merwin & Hulbert or a Webley Royal Irish Constabulary Model 1 to make you happy. But your happiness is of no concern to me.

How Guns Were Really Used in the Old West

The Old West was heavily mythologized, first by the people who actually lived in it (Wyatt Earp, Wild Bill Hickok, and Bat Masterson, to name three, were masterful self-promoters and bs artists.) and then by Hollywood. So we need to take a look at how the guns of that time were actually used.

First, firing a handgun accurately when your life is on the line is nearly impossible for the average person, and “professionals” don’t do much better. This was as true then as it is now. The OK Corral gunfight involved 10 fully qualified participants (of whom two ran away without firing a shot, running away being a highly popular tactic). The fight lasted 30 seconds, and 30 shots were fired. When the fun started, the Earp faction and the Clanton/McLaury faction stood 6 feet apart. Three people were killed and two wounded. This means that, at a range of 72 inches, there was a lot of missing.

The quick-draw rigs beloved of Paladin and Matt Dillon did not begin to appear until the 1920s and were not perfected until the ’50s. Professionals paid some attention to speed rigs, but they had nothing like the buscadero rig, and the average gun toter used whatever the local saddlemaker could cobble together.

The classic “walkdown and quick draw on Main Street” hardly ever happened. Backshooting and killing from ambush were highly regarded, as was bringing a shotgun to a revolver fight.

Most gunfights took place at a few paces. Luke Short and Jim Courtwright (both professional gunmen) were 4 feet apart when they went at it. Courtwright, who was almost certainly drunk, drew his gun first, but it snagged on his watch chain, giving Short a chance to pull his revolver and blow off Courtwright’s gun-hand thumb, further inconveniencing him. Short then shot him four more times.

Often, cartridges refused to fire. Jack McCall’s revolver held five rounds when he murdered Wild Bill Hickok, but only one cartridge fired. The other four were duds.

Professional shootists hardly ever went up against each other. The difference between them was so small that there was a good chance neither would survive. A professional made his living by exterminating amateurs.

And so, with the sulfurous reek of black-powder smoke (which is not black, as Western novelists love to write) in our nostrils, let us slap leather. Here are the greatest handguns of the Old West—every one a Colt.

1. Colt Paterson Revolver

This Colt Paterson revolver, in its original case, from the NRA National Firearms Museum bears the serial number 3. NRA Museum

It began in 1836 in Paterson, New Jersey, where a young inventor named Samuel Colt undertook the manufacture of a .36-caliber percussion handgun which employed a rotating cylinder that held five shots and rendered all single-shot pistols obsolete. Three years later, the design was radically improved by the addition of a loading lever, which enabled a shooter to remove an empty cylinder and replace it with a loaded one in a matter of seconds.

The Paterson was not a commercial success. It was not a robust gun and had very little in the way of power. When production ceased in 1842, only 2,800 had been made, and Sam Colt went into bankruptcy.

But the Paterson’s destiny awaited on the Texas frontier, which was in turmoil. The Comanche nation, which did not take well to the influx of settlers, was raising hell from Mexico to Oklahoma. To fight them, young men organized loosely into companies of Texas Rangers, but they were no match for the men who were later called “the finest irregular light cavalry in the world.” The Rangers’ farm horses could not equal Indian mustangs. Their weapons were single-shot muskets and horse pistols, and they fought on foot. When they went up against warriors who had been fighting on horseback for 200 years, and whose bows could loose 20 arrows in a minute, they were slaughtered.

But things changed. For one thing, the horses improved. It was said you could not join the Rangers then unless you owned a $100 horse, which was a fortune for the time. Captain Jack Hays, considered the father of the Texas Rangers, got command of a company and drilled it mercilessly in the technique of fighting from horseback. And somehow, he acquired Samuel Colt’s Paterson revolvers.

Hays immediately saw the possibilities. Give a Ranger two Patersons and two cylinders per gun, and he could deliver 20 shots without pause.

What Hays’ new tactics and the Paterson could do was demonstrated in June 1844, at a place called Walker’s Creek. Hays’ company of 15 men took on a force of 75 Comanche. When the fight was over, 20 Indians were dead and another 30 were wounded. One Ranger had died and three were wounded.

Nothing like this had ever happened before, and no one who was at Walker’s Creek ever forgot it. This included a young Ranger named Samuel Walker.

2. Colt Walker Revolver

A convincing counterfeit example of the rare Colt Walker revolver. NRA Museum

Colt had gone bankrupt, but the war with Mexico was looming, and the Comanche were still hard at work. Samuel Colt wrote to Samuel Walker and suggested that they might, between them, design a successor to the Paterson that would be far superior. In the words of historian S.C. Gwynne, in Empire of the Summer Moon:

The result, the Walker Colt, was one of the most effective and deadly pieces of technology ever devised, one that would soon kill more men in combat than the Roman short sword. It was a small cannon. It had an enormous 9-inch barrel and weighed in at 4 pounds 9 ounces. Its revolving chambers held [six] conical .44 caliber bullets that weighed 220 grains each. The powder charge—50 grains of black powder—made the new Colt pistol as deadly as a rifle up to 100 yards.

Colt did not have a factory in which to produce handguns, but he talked his friend, Eli Whitney, Jr., into making them at his plant in Connecticut. About 1,500 were ultimately produced, and they, and the Rangers who carried them, went into Mexico with the U.S. Army and set a record of lethality that terrified everyone.

Because of the Walker’s size and weight, it could not be carried on a gun belt, but it established the revolver as the tool you wanted in a desperate situation. Until the introduction of the .44 Magnum in 1955, it remained the most powerful sidearm ever made in the United States, and its influence continues to be felt in such guns as the .460 and .500 Smith & Wesson.

3. Colt Model 1851 Navy

An ivory-handled Colt 1851 Navy revolver. NRA Museum

Designed by Samuel Colt himself, the Model 1851 Navy was so-called because of the naval battle scene engraved on its cylinder. It was the first full-size Colt revolver that you could get out of a holster quickly, and his first major commercial success. Originally a .36-caliber percussion handgun, the Colt Navy was, for its time, a light (2½ pounds) revolver that had unusually fine pointing and handling qualities. It had crude sights, but was considered highly accurate for the time. It was much smaller and lighter than the huge Dragoon model that had followed the Walker, and it was handier than the Model 1860 Army. The Navy was probably the revolver that made gunfighting possible.

The gun’s one notable defect was its lack of power. After the development of fixed ammunition, a great many Navy revolvers were converted to a rimfire .38 round, which was about equal to a .380 ACP. But people just liked the Navy, and its list of highly qualified users is impressive: Buffalo Bill Cody, Doc Holliday, most Texas Rangers up until the Civil War, Nathan Bedford Forest, Captain Jack Hays, and many others.

But it’s primarily because of one man that the Navy gets on this list, and that is James Butler Hickok, Wild Bill, very possibly the most skilled of all pistoleros. Hickok was a lost soul, a failure at nearly everything he tried except violence, but he was very good at that. Unlike most shootists who were unskilled but willing to trade gunfire, Hickok was both very fast and very accurate. He used a variety of handguns, but his trademark was a matched pair of ivory-handled Navy Models that he wore in a sash, grips to the front.

So fearsome was his reputation that even at the end, when he was an alcoholic and suffered from glaucoma, no one was willing to go up against Wild Bill in a fair fight. He was shot in the back of his head by a drifter named Jack McCall as he sat playing cards.

4. Model P, 1873 Colt Single Action Army

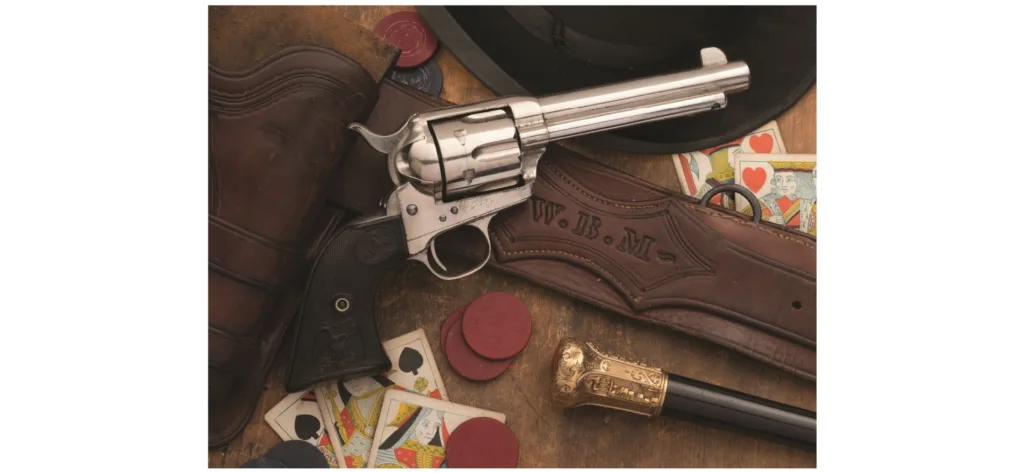

Bat Masterson’s custom Colt Single Action Army revolver. Rock Island Auction Company

With the adaptation of this icon, the Army Ordnance Department, whose record remains mixed at best, struck fire. The 1873, or Peacemaker, remains one of the most recognizable firearms in the world. Of the guns of the Old West, perhaps the only one to achieve something like its fame and popularity is the Model 1873 Winchester lever-action rifle. The Model P was the regulation sidearm of the U.S. Army from 1873 to 1892, but as late as the Second World War, a few Army officers carried it in preference to newer handguns.

It had competition. Remington made the Model 1875 single-action, and Smith & Wesson the Model 3, and both did well and were liked by a lot of people, and both had their advantages.

But the Peacemaker was the sidearm of choice. It combined good reliability with unmatched pointing and balance, and it came in a choice of calibers that Got the Job Done. In its several production runs (the first lasted until 1941 and the onset of World War II) it has been chambered for 30 cartridges, but the two that came to be synonymous with it are the .45 Long Colt and the .44/40.

The Peacemaker came in a number of barrel lengths. The longest, 7½ inches, was the Cavalry Model. The Artillery Model barrel was 5½ inches. There was a 4¾-inch version for civilians, and a 3-inch model (with no ejector rod) that was called the Sheriff’s Model, or the Storekeeper’s Model.

You could get a custom Peacemaker. Bat Masterson ordered his with a 5½-inch barrel, a larger-than-standard front sight, a light trigger, and gutta percha (a rubber compound that was sticky to the touch) grips. Colt was happy to oblige. Some gunfighters ground the front sight off, or tied the trigger back and fanned the hammer. Some of this stuff worked.

Mostly, it was the man behind the gun. And it was some gun.