_We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn more ›

_

Guns link us to famous people, some real and some not real, some good and some as bad as they come.

Inspector Harry Callahan didn’t actually exist, but Dirty Harry stands for something very real in the American psyche. David Crockett is a hero. George Washington is the father of this country. Bonnie and Clyde were as vile a pair of human beings as ever hooked up. George Patton and Dwight Eisenhower are two of the principal reasons that German is not the official language of the United States. John Brown was a madman and a murderer. Robert Ford was a two-bit outlaw and a back-shooter. Ed McGivern was a gentle soul who never hurt anyone. Gavrilo Princip was a fool and an assassin who was indirectly responsible for the deaths of tens of millions of people. Joe Dimaggio is an American idol. Theodore Roosevelt was one of our great presidents, and is the father of conservation in this country.

If ever there was a testament to the fact that a gun is only a tool, no better and no worse than the person who uses it, here is that testament. It is history, written in steel and wood.

1. Annie Oakley’s Parker

This Parker BHE was given to Annie Oakley by her husband, Frank Butler. NRA Museum

“Annie Oakley” is synonymous with “crack shot” because Little Miss Sure Shot, born Phoebe Ann Moses, could really shoot. Born in Ohio in 1860, she learned to hunt at a young age. After the death of her father, she helped provide for her family by market hunting, eventually selling enough game to pay off her mother’s mortgage. When she was 15, she won a shooting contest against a traveling professional shooter named Frank Butler, and eventually the two were married, performed shooting exhibitions together, and joined Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show.

Butler ordered this Parker BHE for his wife in 1903, just as the couple was leaving the Wild West show to strike out on their own. Oakley often shot Parker guns during shows with Buffalo Bill and afterwards. In one of her tricks, she would lie on the ground with three double guns next to her. Butler would throw six glass balls in the air, and Oakley would use the three guns to break all six balls before they hit the ground. Oakley was also a top competitive trap shooter, and is enshrined the ATA Hall of Fame.

This gun is the only shotgun Annie Oakley owned that was decorated with images of herself. Both sides of the receiver show her hunting over a setter. The 12-gauge has no safety, which suggests Oakley used it either for trap shooting or in her shows. —P.B.

2. Bonnie and Clyde’s 1911 and Colt Detective Special

These pistols were pulled from the dead bodies of Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow. The Colt 1911 (top) belonged to Barrow, and the .38 Special (bottom) belonged to Parker. RR Auctions

Forget the hit 1967 movie. In real life, Bonnie and Clyde were career criminals and psychopathic killers who, in their three-year run between 1931 and 1934, murdered nine police officers and three civilians. In Depression-era America, where criminals such as John Dillinger and Pretty Boy Floyd became popular heroes, Bonnie and Clyde caught the public fancy for a while.

Finally, retired Texas Ranger captain Frank Hamer was commissioned to put them out of business. Hamer, who was probably the toughest sumbitch ever to pin on a Ranger badge (nevermind the libelous portrayal of him in the film), assembled a team of other hard cases and began to study the pair’s movements. By and by, he found a pattern.

On the morning of May 23, 1934, on a rural road in Bienville Parish, Louisiana, Hamer and five other officers set up an ambush. At 9:15 they heard Barrow’s V-8 Ford approaching at high speed, and when the car slowed, almost abreast of them, they opened fire.

In one respect the movie was accurate: the automobile was shot to pieces and its occupants were riddled. As one of the lawmen said, when they had emptied their automatic rifles, they picked up their shotguns and fired them dry, and then they took out their handguns and did the same. It’s quite possible that Hamer himself killed Barrow, who had been shot in the head with a .35 Remington rifle, which is what the Ranger carried.

Barrow and Parker were each hit 50 times. When their bodies were searched, the Colt Model 1911 .45 ACP was taken from Barrow’s waistband. The .38 Special revolver was taped to the inside of Parker’s thigh; she knew, in the days before female police officers, that she would not be searched there if taken alive. The Ford was a rolling arsenal. It contained more than a dozen guns and thousands of rounds of ammunition, including 100 20-round BAR magazines.

The pair received heroes’ funerals with thousands in attendance and flowers from everywhere. The funerals of the people they killed were considerably more modest. —D.E.P.

3. “Bo Whoop”

Nash Buckingham nicknamed this HE Grade Super Fox 12-gauge, Bo Whoop after its distinctive report. Photo courtesy of Morphy Auctions

As a Yankee, I will confess to not getting Nash Buckingham’s very southern writing, but I get everything else about him: beloved author, conservationist, expert shot, and owner of Bo Whoop, the most famous waterfowl gun ever. Buckingham liked long-range shooting; his philosophy on waterfowl guns was that you should “never send a boy on a man’s errand.” Bo Whoop was definitely a grown man of a gun, an HE Grade Super Fox with 32-inch Full and Full barrels, bored specially by Philadelphia gunsmith Burt Becker to shoot then-new 3-inch loads of No. 4 shot.

Buckingham shot Bo Whoop—named for the sound of its report—for over 20 years. Then, on December 1, 1948, he and his friend were stopped after a hunt by a warden who wanted to see their licenses. Buckingham leaned Bo-Whoop against the car, forgot about it, and he and his friend drove away. (Buckingham never owned a car nor learned to drive.) He never saw the gun again. Buckingham had another Fox made—Bo Whoop II—but the whereabouts of the original remained a mystery for years until it resurfaced in the early 2000s. It had somehow traveled from Arkansas to Georgia, where a sawmill foreman bought it from one of his workers for $50, threw it in a closet, and forgot about it for 30 years. The foreman’s son inherited the gun, also left it in a closet for many years, then took it to a gunsmith to have its broken stock repaired in 2005. The gunsmith immediately recognized it as the famous missing Bo Whoop. It sold for $200,000 at auction, and was donated to Ducks Unlimited, where it’s on display in Memphis today. —P.B.

4. Buffalo Bill’s “Lucretia Borgia”

Buffalo Bill Cody used this .50 caliber 1866 Springfield to shoot over 4000 bison and earn his infamous nickname. Cody Firearms Museum

Buffalo Bill Cody would become perhaps the most famous American in the world by the early 20th century, touring the states and Europe with his incredibly popular Wild West Show. But in 1866, when he took a job shooting bison to feed crews building the Kansas Pacific Railroad, he was just Civil War veteran Bill Cody from Le Claire, Iowa. During the year and a half that he worked for the railroad, he shot some 4,200 bison with this .50-caliber 1866 Springfield, which he called “Lucretia Borgia” after the aristocrat and alleged femme fatale, because he wanted to name his rifle after something beautiful and deadly.

Apparently a stock Army-issue rifle, Cody’s Springfield wasn’t especially good-looking, but it was deadly in his hands. In his autobiography, he recounted a day-long horseback buffalo-shooting contest with Billy Comstock, another famous hunter:

“I was using what was known at that time as the needle-gun, a breech-loading Springfield rifle—caliber .50—it was my favorite old ‘Lucretia,’ which has already been introduced to the notice of the reader; while Comstock was armed with a Henry rifle, and although he could fire a few shots quicker than I could, yet I was pretty certain that it did not carry powder and lead enough to do execution equal to my caliber 50.”

Cody won the contest, 68 to 48, as well as a bet, and the title of “Greatest Buffalo Hunter,” which is why we remember Buffalo Bill and not Buffalo Billy.

Cody’s fame as a hunter grew after General Philip Henry Sheridan employed him as a hunting guide for dignitaries like the Grand Duke Alexis of Russia. At some point, Lucretia Borgia’s stock broke in two, possibly even in the hands of the Grand Duke, according to one story. The rifle resides in the Cody Firearms Museum today. —P.B.

5. Czar Nicholas II’s Parker

This Parker A-1 Special was thought to be missing until 2007 when it went up for auction. Photo Courtesy of Julia Auctions

Parker is the magic name among American doubles, and four Parker guns in particular achieved near-mythic status. Three of these are famous missing Invincible Grade guns. The fourth is this A-1 Special, made for Czar Nicholas II of Russia. Ordered from Parker for the Czar by a group of his officers, the gun was made shortly before the Russian Revolution. But the Czar was killed before it was ever delivered. The gun, which no one but its makers ever saw, became a mystery—almost the Maltese Falcon of fine guns. Some believed it was consumed in the flames of the Russian Revolution, others that it never existed at all. In the end, the answer to the mystery was disappointingly mundane: the gun never left the U.S. because the Revolution started and Parker lost touch with the officers who ordered it. Instead it was sold to a man in New York. Neither he nor his heirs said anything about it until 2007, when the latter put it up for auction.

Deeply engraved with scrolls and roses, the Czar’s gun is a 12-gauge with 32-inch Full and Full barrels. The owner had the original stock replaced by Abercrombie and Fitch in the 1930s with a longer, straight-gripped version. An A-1 Special cost $375 plus $18.75 for ejectors when it was made. The Czar’s Parker brought $287,500 at auction in 2007. —P.B.

6. David Crockett’s Old Betsy

David Crockett gave this .40-caliber rifle to his son right before he left for Texas and the Alamo. Texas General Land Office

Crockett, who detested the name “Davy,” became a legend in his own lifetime, along with James Bowie, who died with him at the Alamo. We don’t know exactly how Crockett died, or even which rifle he had at the time. We do know that he owned a number of them, and that the provenance of this one is particularly good.

It’s a .40-caliber gun that was probably built by James M. Graham of Franklin County, Kentucky. The rifle was presented to Crockett by the citizens of Nashville, Tennessee, on May 5, 1822, in recognition of his service in Congress. Crockett gave the rifle to his son John Wesley before he left for Texas in 1835. Since then, it has suffered from multiple owners and considerable neglect, resulting in its conversion from full- to half-stock and from flintlock to percussion.

Crockett did not use this gun during the battle at the Alamo. Whatever he did carry was either lost or destroyed. —D.E.P.

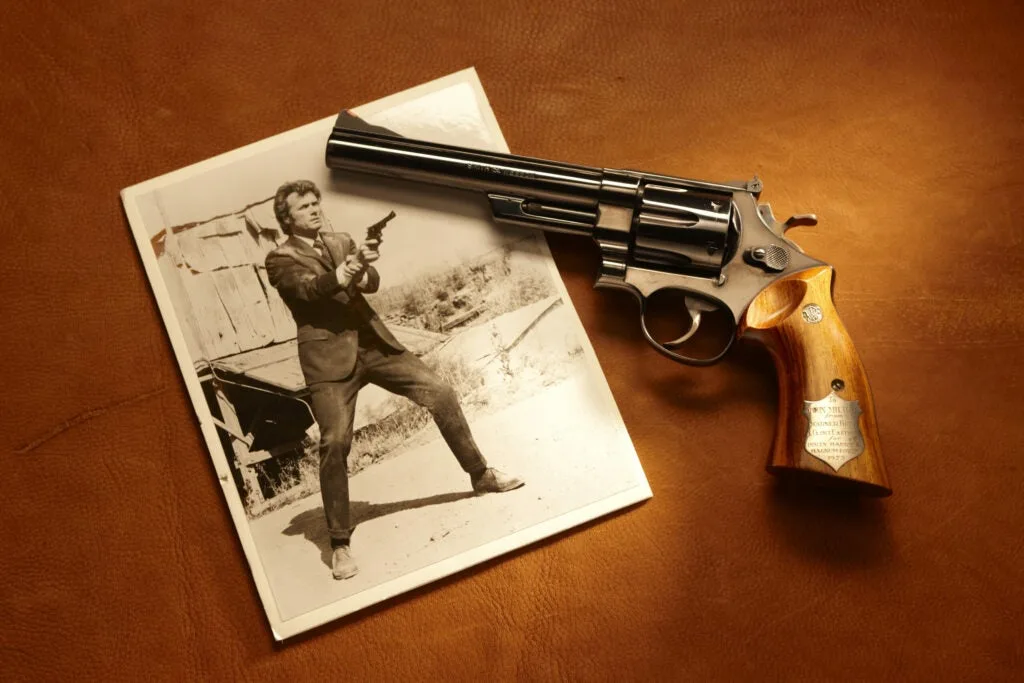

7. Dirty Harry’s .44 Magnum

Dirty Harry’s Model 29 Smith & Wesson Revolver in .44 Magnum. NRA Museum

In 1955, Smith & Wesson, in collaboration with Remington, introduced the Model 29 revolver, chambered for the brand-new .44 Magnum cartridge. It was a beautiful gun, one of the finest revolvers ever made in America, but it was so much more powerful than anything before it that people didn’t quite know what to make of the gun.

That is, until the appearance on screen of San Francisco Police Inspector Harry Callahan, called “Dirty” Harry because of his lack of respect for Safe Spaces, Trigger Warnings, Miranda Rights, or much of anything else. The Model 29, in Dirty Harry’s hand, seemed nothing less than the Wrath of God.

The 1971 film was a hit, and one of its early scenes became iconic. Callahan breaks up a bank robbery by shooting everyone involved and their car. Then, confronting a wounded robber lying on the sidewalk, he cocks the revolver, aims it at the man’s head, and says:

“But being this is a .44 Magnum, the most powerful handgun in the world, and would blow your head clean off, you’ve got to ask yourself one question: ‘Do I feel lucky?’ Well do you, punk?” These words are now as firmly engraved in the American psyche as “We hold these truths to be self-evident.”

Before Dirty Harry, the Model 29 was a poor seller. People bought one, fired one cylinder of ammo, and put the gun up for sale. The Model 29 was not even in production at the time the movie was slated to start filming, so Eastwood went directly to Smith & Wesson, who assembled three 29s out of spare parts on hand. The script originally called for a nickel-plated model with a 4-inch barrel. However, the only parts available were blued, and the only barrels 6 1/2 inches, so that’s what was used.

After Dirty Harry, you couldn’t find a 29 unless you were willing to pay up to triple the list price. And while the original blue-steel Model 29 has been replaced by the stainless Model 629, the demand has never faltered.

After the film, and its first follow-up, Magnum Force, Eastwood and Warner Brothers had one of the three revolvers cleaned up, and a presentation plate mounted on its grip. It was presented to screenwriter John Milius, who is a gun nut of the first magnitude, and who in turn donated it to the NRA Museum. There it remains, an American icon. —D.E.P.

8. Dwight Eisenhower’s Winchester Model 21

Dwight Eisenhower’s favorite 20-gauge Winchester Model 21. NRA Museum

Our second-most-golfing-est president (number one isn’t who you think it is; it’s Woodrow Wilson, according to presidentialgolftracker.com), and one of our most underrated, Dwight Eisenhower also loved the outdoors. It was Ike who built the skeet field at Camp David, and he would have the streams there stocked with trout before he arrived. A lifelong bird hunter, from his boyhood in Kansas through his retirement to a farm full of pheasants near Gettysburg, he owned a number of shotguns, but his favorite was this Winchester Model 21, a straight-gripped 20-gauge with the receiver worn from hours in the field.

There wasn’t much that was ostentatious about Dwight Eisenhower, and so it’s fitting that his favorite gun was made in the United States and doesn’t bear much decoration. The otherwise plain receiver has a gold pheasant inlaid on one side, a gold grouse on the other, five stars on the floorplate, and “DDE” on the trigger guard. The gun was presented to Eisenhower by Robert Woodruff, president of Coca Cola, and an engraving on the stock medallion reads: “To a straight shooter from a friend”.

Mamie Eisenhower gave the Winchester to the NRA in 1969, the same year Ike died. The Secret Service agent who drove Mrs. Eisenhower to NRA headquarters shared a story about Eisenhower and his Model 21. A foreign dignitary visiting the ex-president at Gettysburg brought him a lavishly engraved gun. As they got ready to hunt, Eisenhower took his new gun, and the members of the Secret Service detail were told to take guns from the cabinet. The Model 21 was the only gun left when the agent who drove Mrs. Eisenhower reached in.

“Don’t touch that 20-gauge. It’s the president’s favorite,” said one of the other agents.

Eisenhower, who was close enough to overhear, told him: “Go ahead and take it. They were made to be shot.” —P.B.

9. Ed McGivern’s Smith & Wesson Revolver

Ed McGivern preferred revolvers like this .38/44 Smith & Wesson Police Target Model because automatics cycled too slowly for him. NRA Museum

The fastest gun in the West was not a steely-eyed shootist on the order of John Wesley Hardin; it was a short (5’3”), dumpy, sign painter who never hurt a soul, but who could do things with revolvers that defied human capability. Ed McGivern was born in 1873 and was fascinated with guns from childhood. In adulthood, he became obsessed with exploring the limits of what handguns could do.

Through endless practice and experimentation, he found out. McGivern favored modified Smith & Wesson double-action and Colt Single-Action Army revolvers. He tried automatic pistols early on but found that they cycled too slowly for him. He could pull the triggers faster than the guns could operate. He preferred gold-bead front sights above all others, and all his guns were equipped with them, some mounted quite high.

This .38/44 Smith & Wesson Police Target Model Revolver was used for one of his most remarkable feats. On August 20, 1932, McGivern fired two groups of five shots at 15 feet in 2/5ths of a second, each group small enough to be covered by a half-dollar. This was timed by stopwatch. There is, I recall, a film of McGivern doing this, and the shots come so fast that they’re indistinguishable; it sounds like canvas ripping.

On one occasion, McGivern was bet that he couldn’t put six shots in a tin can that was thrown 20 feet in the air, before it hit the ground. Intrigued, he devoted 30,000 practice rounds to the problem and then tried it for real. When the can landed it had six holes in it.

He could hit a thrown dime and drive a nail with bullets. There was seemingly no feat too difficult for him to perform. His book, Fast and Fancy Revolver Shooting, is still a classic. Arthritis eventually took his gifts, and some of his stunts have been equaled, or even surpassed, but this modest little man is still considered by many to be the greatest pistolero of all time. —D.E.P.

10. Gavrilo Princip’s FN Model 10

Gavrilo Princip used this .380 ACP FN Model 10 to assassinate The Archduke of Austria, Franz Ferdinand. Jack Sullivan/Alamy

Gavrilo Princip was a 19-year-old Serbian who was a member of a political assassination group called the Black Hand, and on June 28,1914, he fired two shots from this .380 ACP FN Model 10 automatic that killed Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and his wife Sophie, as they rode in a motorcade in Sarajevo.

The two shots were fired at a time when all of Europe was cocked and locked, waiting for an excuse to have a war. Wars, up to then, had been civilized affairs that didn’t last overly long, did not kill unacceptable numbers of people, did not inconvenience the participating countries too much, and resulted in promotions for surviving officers of all ranks.

However, these were new times, and by committing his dual murder, Princip triggered a war that lasted from August 1914 to November 1918. His two shots were the first of 2 billion (a guess; there is no confirmed number) small arms rounds and nearly as many artillery shells. These took the lives of 7 million civilians and 10 million military personnel, and annihilated generations of young men. The war also destroyed the Austro-Hungarian Empire, led to the unraveling of the British Empire, and was the direct cause of World War II.

Princip was seized immediately and put on trial with his fellow Black Hand conspirators. Because he was too young by 27 days to receive the death penalty, he was sentenced to 20 years in prison. He would have suffered less if he had been hanged. Princip was held in solitary confinement, chained to the wall, in Terezin Fortress in what is now the Czech Republic. He contracted skeletal tuberculosis, resulting in the amputation of his right arm, and was killed by the disease and malnutrition on April 28th, 1918. At the time of his death, he weighed 88 pounds.

His pistol is on display at the Vienna Museum of Military History. —D.E.P.

11. General Patton’s Pistols

General Patton carried both of these revolvers during World War II. Photo courtesy of the General George Patton Museum

“RHIP” says the U.S. Army, “Rank has its privileges,” and no one took more advantage of this than General George S. Patton, who ignored the drab and underpowered .32 Colt Automatic Pistol that general officers were authorized to carry in World War II. Patton distrusted automatics, ever since as a second lieutenant he diddled with the trigger of his Model 1911 and shot himself in the leg.

In 1916, while stationed near El Paso, Patton bought a Model 1873 Colt Peacemaker. It’s a .45, highly engraved, with a silver-plated top strap and carved ivory grips. It was not for decoration. Along with General John Pershing’s Expeditionary Force, Patton invaded Mexico in that year and killed three bandits with it.

As World War II approached, and feeling the need of further armament, Patton acquired his .357 Magnum S&W Model 27 in 1935. It has a 3-1/2-inch barrel, is blued, and originally came with walnut grips, which Patton quickly replaced with carved ivory. (During World War II, after he had become a general, and famous, Patton was asked by a reporter [He detested the breed.] about his fondness for “pearl-handled” guns. Patton fixed the man with a withering sneer and said, “Only pimps carry pearl-handled guns.”) He called it his “killing gun,” although there’s no evidence that he ever killed anyone with it.

The two handguns rode in fast-draw holsters, the Peacemaker always on the right, the S&W on the left. The two revolvers were a Patton trademark, along with the tailored uniforms, spit-shined riding boots, polished helmet liner with three (and later four) big stars, and camera and binoculars around the neck.

Patton was a terror to his own troops as well as to the Germans. Field & Stream’s late, great Fishing Editor Al McLane served as an infantryman in Europe during WWII and personally witnessed an ass-eating Patton delivered to a full colonel who was not advancing fast enough to suit him. Al said it was the most frightening thing he saw during the entire war.

For many years the revolvers were at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, from which Patton graduated in 1909 with undistinguished grades. They now reside at The Patton Museum in Ft. Knox, Kentucky. —D.E.P

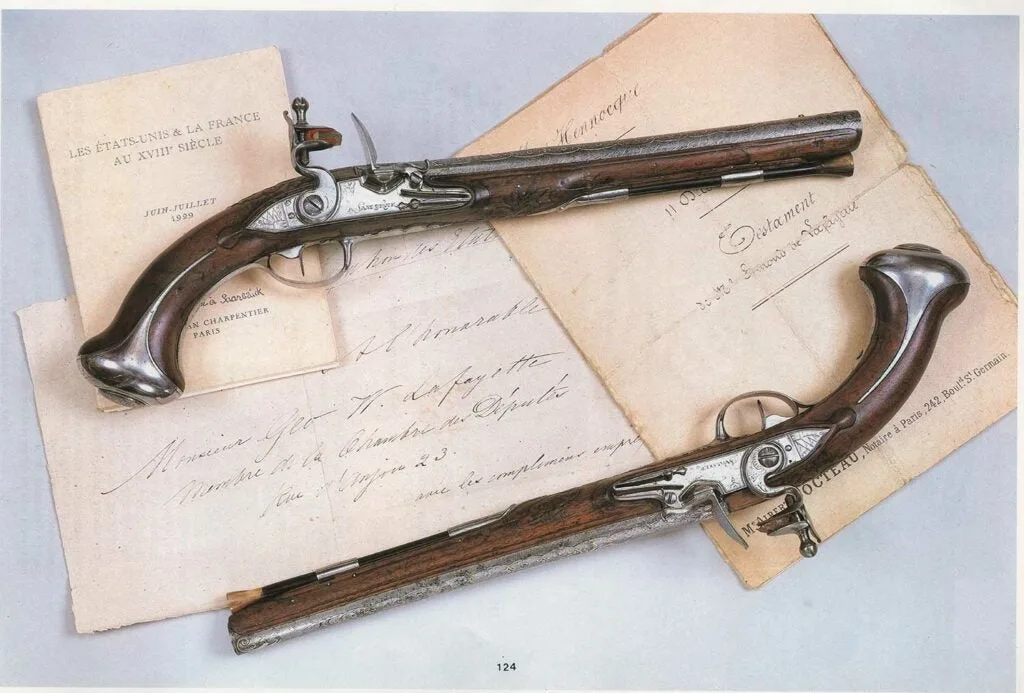

12. George Washington’s Pistols

George Washington’s .57-caliber flintlock saddle pistols. Fort Ligonier Museum

Any gun can belong to a famous person. This pair of .57-caliber flintlock pistols belonged to three—all war heroes and two of them presidents.

Like many French army officers, the Marquis of Lafayette was inspired to join the colonial rebellion because he believed in it, and anyway, it was a bonus opportunity to fight Englishmen. Denied passage to the Colonies by the French government, the 19-year old Marquis bought his own ship and sailed across the Atlantic and into American history. In 1778, he decided to buy a gift for his commander, mentor, and fellow Freemason, General George Washington. And being rich enough to buy his own ship, the Marquis could afford a very nice gift. He chose an ornate pair of pistols made by Saarbrucken gunsmith Jacob Walster. Washington carried the guns (that is, his horse did, they were saddle pistols) throughout the Revolution and during the Whiskey Rebellion. They passed from Washington to his nephew to his nephew’s son in law to Andrew Jackson in 1824, the year of his first, unsuccessful, bid for the presidency.

In 1824 and 1825, Lafayette toured America, and was greeted by adoring crowds in all twenty-four states. He visited Jackson at the Hermitage, his Tennessee plantation, where Jackson showed Lafayette a pair of pistols, asked if they looked familiar, then gave them back to him. Today the pistols reside at the Fort Ligonier Museum in Pennsylvania. —P.B.

13. The Hamilton-Burr Duelers

The pistols of the famous duel that resulted in the death of Alexander Hamilton. JPMorgan Chase & Co.

In a better time than this, politicians who had differences did not settle them by posting Tweets; they did it with pistols or swords. Dueling, in the early 19th century, was illegal in most states, but widely practiced. A gentleman could not ignore a challenge and retain his honor, such as it was.

These .56-caliber duelers, made by London gunsmith Robert Wogdon, were purchased there in 1797 by Colonel John B. Church, the brother-in-law of Alexander Hamilton. Hamilton, a distinguished politician and military officer, had a long-standing feud with Aaron Burr, a man of near-equal attainment, and in 1804, things got to a point where blood had to be spilled.

The duel was to be fought with pistols at Weehawken Heights in New Jersey, overlooking the Hudson River. For guns, Hamilton turned to Colonel Church. Both are smoothbores with octagonal barrels, bead front sights and notch rear, and checkered stocks. The triggers set—you push them forward to cock them, and then they go off at a touch. Dueling pistols were neither supposed to be rifled nor over .50-caliber, as either made the likelihood of death a little greater than men of honor liked.

On the morning of July 11, 1804, the parties crossed the Hudson from Manhattan. At 7 A.M. Hamilton and Burr stood probably 10 yards apart and fired on a signal. There are two accounts of what happened next. One says that Hamilton fired first, deliberately aiming above Burr, and that his shot clipped a tree branch. Burr, assuming that he had been fired on, returned the shot and struck Hamilton in the stomach, just above the right hipbone—in those times, a mortal wound.

The other version says that Burr fired first, hitting Hamilton, and that Hamilton’s gun went off as he fell and that he did not know it had discharged.

Honor having been satisfied, the party returned to Manhattan, where Hamilton died the next day. A charge of murder was brought against Burr, with his seconds named as accomplices, but he was never prosecuted. Nonetheless, the duel ruined him. He lived 30 more years, but his public career was over, and he died penniless.

The pistols were returned to Colonel Church, and eventually passed to his grandson Richard Church. When Richard Church organized a volunteer company to fight in the Civil War, he felt in need of a sidearm, so he had one of the Wogdon pistols converted to percussion. It is, however, almost certain that the flintlock gun killed Hamilton.

The guns remained together and became the property of Mrs. Mary Helen Church Gilpin, a great granddaughter of Colonel Church, and in 1930 she sold them to the Chase Bank for a reported $2,500.

The bank had been organized, many years before, by Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr. —D.E.P.

14. Herb Parson’s “Mae West” Model 12

Herb Parson’s fast-shooting, nickel-plated Winchester Model 12. Cody Firearms Museum

Before Tom Knapp, there was Herb Parsons, last of the old-time exhibition shooters. Born in 1908, Parsons taught himself to hit walnuts and chunks of coal in the air with a rifle long before he ever saw Winchester’s star exhibition shooter, Ad Topperwein, perform. Once he did, Parsons knew what he wanted to do with his life, and he eventually replaced his idol. Parsons toured the country, wowing crowds with a variety of Winchester rifles and shotguns. His shooting ability took him to Hollywood, where stood off-camera on the set of Winchester ’73, shooting coins out of the air as Jimmy Stewart pretended to with blanks. Back then, movie stars shot and hunted, and Parsons shot trap with Clark Gable and Roy Rogers, and hunted ducks with Wallace Beery.

Parsons’ signature trick was throwing seven clay targets in the air and breaking them all before they hit the ground. For that he used the Model 12 Winchester, which he called “Mae West.” A sure-pointing, slick pump gun, the Model 12 was ideal for shooting multiple targets in a hurry. It had a secret advantage, too: it lacked the trigger disconnector of modern pumps. Parsons said he accomplished his feat by “holding down the trigger and pumping like hell.” “Mae West,” Parson’s personal nickel-plated Model 12 is on display at the Cody Firearms Museum. —P.B.

15. Jack O’Connor’s “No. 2 Rifle”

Jack O’Connor had this Winchester Model 70 modified by gunsmith Al Biesen. John Hafner

O’Connor bought the .270 Winchester Model 70 in 1959 from a hardware store in Lewiston, Idaho. The rifle was highly accurate right out of the box, but crude to a rifleman of O’Connor’s taste and sophistication, so off it went to Al Biesen, the Spokane gunsmith who was O’Connor’s favorite.

Biesen was not only a craftsman of the first order, but something of an ergonomic genius. His rifles have a “feel” to them, which you can pick out blindfolded. Biesen re-stocked the Model 70 in plain walnut—this was to be a working gun—tuned the trigger, replaced the horrid aluminum floorplate and trigger guard with steel, and mounted a straight 4X Leupold scope very low and far forward. The rifle was a masterpiece, and O’Connor sang its praises for the next dozen years until he retired.

If you shoulder it, you’re struck by its 8-pound weight, which was considered light for 1960 (the year it was completed) but not by today’s standards, and by the fact that it’s been well cared for but has obviously had a ton of use—two African safaris, plus heaven knows how much else hunting.

O’Connor wrote that he wanted to be buried with the No. 2 gun. Probably he was kidding. —D.E.P.

16. Jim Corbett’s .275 Rigby

Jim Corbett’s .275 Rigby was presented to him as a gift for killing a notorious man-eating tiger in India. Simon Barr/Tweed Media

You’d have to work hard to convince the average Snowflake of it, but the big cats—lions, tigers, leopards—actually eat people. Some of them eat lots of people. Nowhere was this more in evidence than in India during the early part of the 20th century when the population began to explode and there were still a great many tigers and leopards left in the wild.

Some of these predators ran up body counts that went over 100, and the hunter who was often called upon to reason with them was a self-effacing British railroad official named Jim Corbett. Corbett’s exploits, and his books about them, made him world famous. He was the real thing—stupendously brave, supremely skillful, and always sympathetic toward the animals he was obliged to destroy.

He did much of his hunting at night, always alone, accompanied only by a small dog he called Robin. It’s well to remember that he did this before antibiotics, when even a non-fatal mauling by a big cat could result in a fatal infection.

His .275 Rigby (the British name for the 7×57 Mauser) was built in London in 1905. Shipped to Calcutta, it lay unsold until 1907, when it was presented to Corbett by the United Provinces Lieutenant Governor in thanks for putting paid to the Man-Eating Tigress of Champawat, which had accounted for a confirmed 436 human deaths.

It’s a single-square-bridge Mauser with a 25-inch barrel, and it’s now owned, once again, by John Rigby and Company in London. Corbett used it, a lot, and ended the careers of other man-eaters with it. He eventually gave up predator control and dedicated the rest of his life to ensuring the survival of the big cats. Today, the principal wildlife refuge for tigers in India is named for him. —D.E.P.

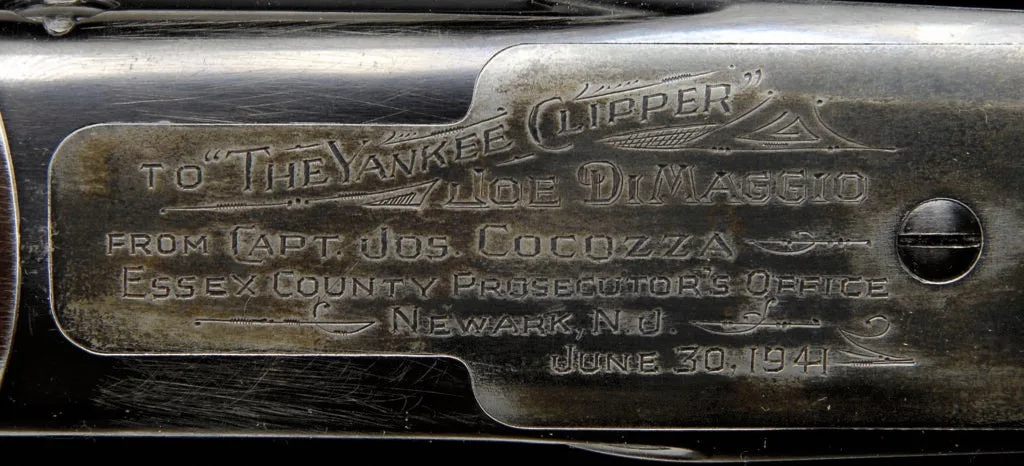

17. Joe DiMaggio’s Model 21

The engraving on the floorplate of Joe DiMaggio’s Winchester Model 21. Photo Courtesy of Julia Auctions

“Graceful” is the adjective most often associated with Joe DiMaggio, but the Yankee Clipper was also known as “Joltin’ Joe,” because he had the strength to hit the long ball. It’s fitting that his shotgun was a Winchester Model 21, which is a gun of elegant lines, designed to be as strong as a double could be.

In 1941, DiMaggio set one of baseball’s sacred records, hitting safely in 56 consecutive games, passing George Sisler of the St. Louis Browns. This 21 was presented to him, in recognition of that feat. The floorplate reads: “To “The Yankee Clipper” Joe DiMaggio From Capt. Jos. Cocozza Essex County Prosecutor’s Office Newark, N.J. June 30, 1941”.

The gun was made for duck hunting, with 30-inch barrels, and a tight (.029) choke in one barrel and a tighter (.032) choke in the other. DiMaggio loved to hunt ducks, and there’s no question he used the gun for hunting, because the stock was burned in a duck-blind fire and replaced in 2007 by a subsequent owner. The Yankee Clipper’s Model 21 now resides in a private collection. —P.B.

18. John Brown’s Sharps

John Brown’s .44-caliber Sharps sporting rifle. The Smithsonian Institution

No one trampled the line between “domestic terrorist” and “freedom fighter” the way John Brown did. Raised with a deeply held, lifelong belief in the equality of all races, Brown chose to fight slavery head-on. His heart was in the right place, but his methods were extreme, even for Bleeding Kansas. In 1856, Brown led his four sons and two followers on what is now known to history as the Pottawattomie Creek Massacre. They literally went medieval on five pro-slavers, since nothing says “middle ages” quite like hacking people to death with broadswords. Brown, however, was the one member of the party who didn’t use a sword. Instead, he shot one of the dying victims, quite possibly with this Sharps rifle, which today is in the Smithsonian collection.

This particular Sharps was not one of the famous “Beecher Bibles” sent to Kansas by New England abolitionists to arm anti-slavers, but was Brown’s personal firearm—a .44-caliber sporting rifle. He carried it throughout his 1856 Kansas campaign. In 1857, Brown gave the rifle to Charles Blair of Collinsville, Connecticut, the man Brown contracted to make the pikes with which he planned to arm the slaves who would rise up in revolt after the raid on Harper’s Ferry. Instead, Brown was captured by a force led by Col. Robert E. Lee, arrested, and hanged, becoming an abolitionist martyr and setting the nation on an irreversible track to civil war. —P.B.

19. Liver-Eating Johnson’s Hawken

The mountain man who inspired the movie, Jerimiah Johnson, carried this .56-caliber Hawken. Cody Firearms Museum

His real name was John Garrison, and he was born in Little York, New Jersey, in 1824. However, he’s known to history as Liver-Eating Johnson, and he would be forgotten today except for a purported biography called Crow Killer, by Raymond Thorpe; a novel titled Mountain Man, by Vardis Fisher; and a 1972 movie, Jeremiah Johnson, which starred Robert Redford. One thing is certain: The real man bore not the slightest resemblance to Robert Redford.

Johnson stood just under 6-feet tall and weighed somewhere between 230 and 260 pounds. He was a man of prodigious strength and extremely bad temper. He served as an Army scout and cavalryman, and he arrived in the Rockies when the great days of beaver trapping were already gone, so he made his living by trading, hunting, and chopping wood. He worked for a while as a deputy marshal.

Early in his career, he settled on a Hawken.

The Hawken was what became of the Kentucky Rifle when it reached the Rocky Mountains. The long barrels were drastically shortened; the brass trim and figured maple were replaced by iron and pewter and plain walnut; the calibers increased from .30 to .40 to .50 to .65. The barrels were far heavier so you could cram in a super charge of powder if you needed it. Set triggers were standard, as was percussion ignition. Most Hawkens weighed 10 to 12 pounds.

Johnson’s gun is typical; it’s a .56, drab and unpretentious. There is some hooey in the movie about his trading for a .30 Hawken when he first heads for the High Country. This is nonsense. It’s not even known if there was such a thing as a .30 Hawken, as they were made for big animals and long range.

Unlike most of his brethren, Johnson lived into old age, and died in a veteran’s home in Santa Monica, California, in 1900. For years, his body was buried in a veteran’s cemetery in Los Angeles. In 1974, a group of schoolchildren, aided by Robert Redford, had him disinterred and re-buried in a cemetery outside Cody, Wyoming. Redford was one of his pallbearers. Whoever inscribed his headstone had a certain sense of poetry: It lists his name and cavalry unit, and his years of birth and death. And below that, the inscription reads: “NO MORE TRAILS”. —D.E.P.

20. Meriwether Lewis’ Girandoni Air Gun

The Girandoni Air Gun was state of the art in the early 19th century. NRA Museum

Around the turn of the 19th century, it seemed as if air might give gun powder a run for its money as a propellant. The Girandoni air gun, adopted by the Austrian Army and used from 1780 to 1815, came in .46 caliber, was accurate to over 100 yards, and could fire 20 shots without reloading. It was smokeless, too, a major advantage in the era of black-powder combat. The stock served as an air reservoir on some models, while others had a spherical reservoir, and it had a tubular magazine alongside the barrel that allowed the shooter to tip the muzzle into the air, push a latch, and drop the next ball into the chamber.

The gun had its disadvantages. It was fragile, and it took 1,500 pumps to charge the reservoir, after which it could shoot 40 times without appreciable loss of velocity. The Austrians eventually brought wagons with air pumps into the field to help with reloading, although soldiers would carry extra charged stocks with them into battle.

Somehow, Meriwether Lewis got hold of a Girandoni gun, and he brought it with him on the Voyage of Discovery. The gun played an important part in the expedition: Often, upon meeting natives, Lewis and Clark would dress in their good uniforms, strike up their small fife and drum corps, and give gifts to the Indians. Lewis would then give a marksmanship demonstration with the air gun, showing off its range, accuracy, and extremely rapid-fire capabilities (for it’s time). The Native Americans were always highly impressed, and, perhaps not coincidentally, disinclined to attack a group possessing one or maybe many of these rapid-fire rifles. Lewis and Clark lost only one man—to a burst appendix—on the expedition. —P.B.

21. Napoleon’s Presentation Fowler

Napoleon’s flintlock fowler is ornately decorated with gold, silver, and platinum. NRA Museum

This ornately decorated flintlock fowler owned by Napoleon Bonaparte was once half of a pair. The other gun, a double rifle, was stolen from a museum in Geneva, and its whereabouts are unknown. This gun bears the French royal coat of arms, so it clearly wasn’t originally made for Napoleon, but he owned it before presenting it to one of his generals, Marshall Marquis Faulte de Vanteaux of Limoges. Both barrels are inlaid with gold and the stock with gold, silver, and platinum. It even has the 18th century’s version of a recoil-reducing comb: a velvet-covered, goose-down-padded cheekpiece. —P.B.

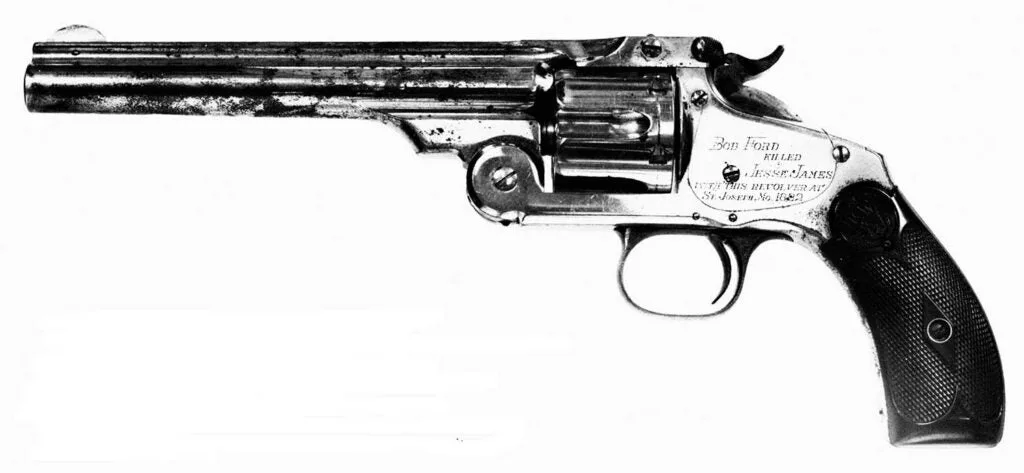

22. Robert Ford’s Pistol

Although Robert Ford stated that he killed Jesse James with a Colt, this Smith & Wesson No.3 was the one he surrendered before being jailed for the shooting Lordprice Collection/Alamy

One side of the .44 caliber Smith & Wesson No. 3 reads, “Bob Ford killed Jesse James with this revolver at St. Joseph, Mo., 1882″—and it may even be true. After the shooting, Ford said in a sworn statement to the Kansas City Daily Times that he used a Colt SAA .45, but the .44 is the pistol he gave to his jailer, a man named Corydon Craig, after the shooting. It was Craig who had the pistol engraved, presumably because Ford told him it was the gun he’d used.

Upon his release and pardon, Ford then spent the rest of his short life simultaneously trying to cash in on his crime and running from it. Chased out of Missouri, he appeared for a while in a stage show entitled “Outlaws of Missouri,” in which he retold the story. In the stage version, he downplayed the part about shooting Jesse James in the back, which led to his being hooted out of several western towns.

Ford opened various failed saloons and dancehalls throughout the west, and had just opened another and was facing away from the door, when karma, in the form of one Edward O’Kelley, carrying a sawed-off shotgun, walked into the tent-saloon. Rather than shoot him in the back, O’ Kelley said “Hello Bob,” waited for him to turn around, and shot him dead for reasons O’Kelley himself never fully explained. He may have had no more motive than to become the man who shot the man who shot Jesse James. —P.B.

23. Teddy Roosevelt’s Fox

The 12-gauge FE grade A.H. Fox Company shotgun Teddy Roosevelt took with him to both Africa and South America. Photo Courtesy of Julia Auctions

Shortly before Theodore Roosevelt left on his famous nine-month Africa safari, the A.H. Fox Company presented him with an FE grade 12-gauge shotgun. Roosevelt wrote to Ansley Fox: “It is the most beautiful gun I have ever seen… I am almost ashamed to take it to Africa and expose it to the rough usage it will receive. But now that I have it, I could not possibly make up my mind to leave it behind.”

Later, in his account of the trip, African Game Trails, Roosevelt wrote: “I have a Fox number 12 Shotgun; no better gun was ever made.” Fox used that quote in ads to sell guns for years and years. The Fox also accompanied Roosevelt on his disastrous trip with son Kermit down the River of Doubt in the Amazon Basin, which was marked by endless grueling portages, accidental death, murder, and Roosevelt’s near-death from fever. It may even have been the trip that ultimately broke the unbreakable TR’s health. If you have not read Candice Millard’s River of Doubt, a page-turning account of the trip, shut off this computer and go read it immediately. —P.B.

24. Warren Page’s “Old Betsy Number One”

The wood and steel on Warren Page’s 7mm Mashburn Super Magnum were drilled out to make it lighter. Heritage Auctions

From 1950, when she was delivered to Warren Page by Mashburn Arms in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, until his resignation as Field & Stream Shooting Editor in 1972, this 7mm Mashburn Super Magnum was probably the most famous hunting rifle in the world. (There was a Number Two, which was fancier, and which he kept as a backup rifle, but never used.) Old Betsy Number One was, for its time, a radical rifle. Every part, wood and steel, was either Swiss-cheesed or hollowed out. The end result weighed only 8 pounds scoped, loaded with 3 rounds, sling attached. This, in an era when an equivalent rifle would have scaled 10 or 11 pounds.

With it, Page killed 475 head of big game of all shapes, sizes, weights, and origins. Probably, his most notable trophies were his Alaska blue bear and African bongo.

Even though Page was a championship-level benchrest shooter who knew about minuscule groups, Old Betsy shot no better than a 1-1/2 MOA. Page, being an experienced hunter, knew that he didn’t need better.

Old Betsy Number One wore the same straight 4X scope throughout her career. Like many of his generation, Page did not trust variable scopes or think you needed them. He knew that, in the end, it’s skill that counts. —D.E.P.

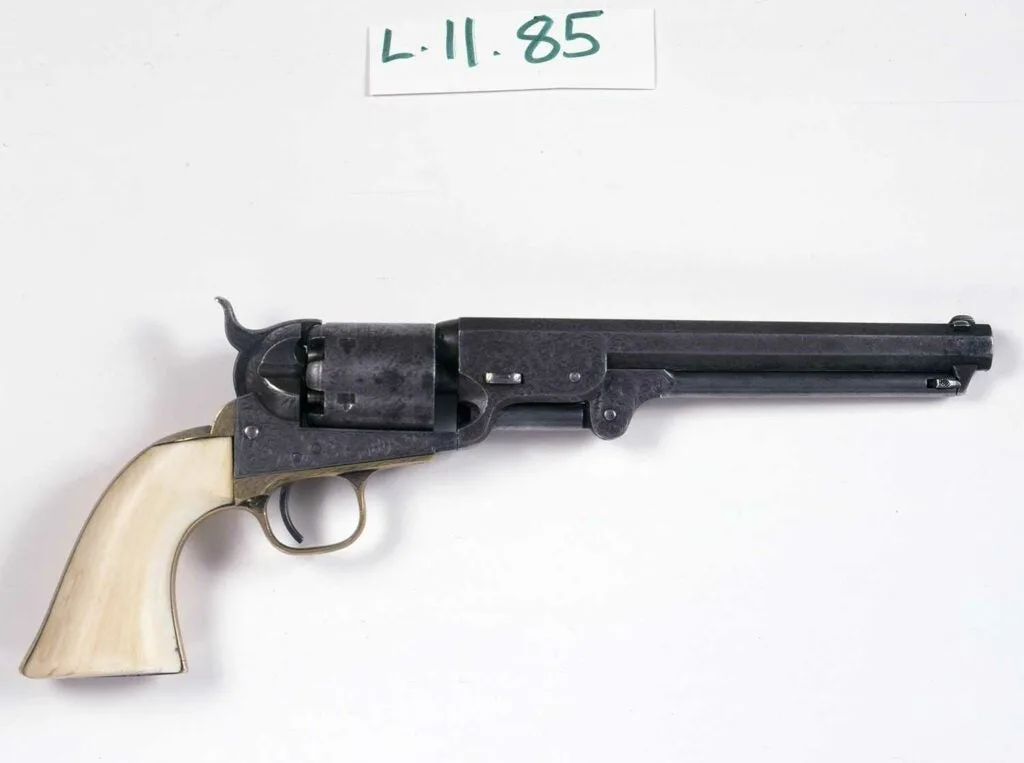

25. Wild Bill Hickok’s 1851 Navy Colt

Wild Bill Hickock’s .36-caliber Model 1851 Navy Colt. Cody Firearms Museum

Hickok, like David Crockett, became a celebrity during his life and, unlike Crockett, was fond of improving on the truth. In Hickok’s case, however, even the truth makes a rip-roaring tale. Hickok, whose real name was James Butler, was an Indian fighter, Army scout, lawman, professional gambler, and wild west show performer, but mostly he is known now as a shootist—a gunslinger, and maybe the best of all of them.

According to the legends, Hickok killed legions of men, but the best estimates range between six and 10. The revolvers he favored were a pair of nickel-plated, ivory-handled .36-caliber Model 1851 Navy Model Colts. They were percussion guns, and he stuck to them even after the advent of cartridge-firing pistols. He carried them butt-forward in a sash, and drew with his hands reversed.

Hickok came to fame with his killing of one Davis (Dave) Tutt in Springfield, Missouri, in 1865. In one of the rare Old West face-offs (as opposed to the far more popular back shootings), the two men stood 75 yards apart in the town square and fired simultaneously. Tutt missed. Hickok didn’t. He rested his gun barrel across his forearm and killed Tutt. The fight was written up in Harper’s magazine, a well-known chronicler of bloodshed, and made Hickok a national celebrity.

Hickok could also shoot fast—sometimes, too fast. In 1871, as marshal of Abilene, Kansas, he was busy confronting a mob when he heard footsteps running up behind him. He turned and killed the man, who turned out to be his deputy, Mike Williams. Hickok was fired not long thereafter and never worked as a peace officer again.

By 1876 Hickok had hit bottom. He was unemployable, suffering from glaucoma, and drinking hard. He wound up in Deadwood, South Dakota, to gamble, and was shot dead from behind while sitting at a card table by a saddle tramp named Jack McCall. Hickok was holding aces and eights, now known as the dead man’s hand. —D.E.P.