MOST KIDS try smoking. They get caught, get a whipping, or get sick, and that’s it. But before I was through with my initial venture with the weed, my grandmother hated me, my uncle Al nearly committed multiple murder, my parents were ready to put me up for adoption, and the Wisconsin Game Commission and the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals could have had me put away for life.

If my father hadn’t been born in tobacco country, I’d probably be a smoker today, worrying about deadly respiratory diseases. The worry would lead to that gnawing craving for a cigarette. The cigarette would lead to more worry about smoking too much.

But I never touched a cigarette after the deer attacked my grandmother.

Our Chicago home was centrally located between the homes of my father’s family in Missouri and the homes of my mother’s relatives in northern Wisconsin. My father delighted in taking the products of one region to the other—mixing the cultures. He would take enormously smelly cheeses from Wisconsin to Missouri where my paternal grandfather would take time out from hunting squirrels to moan with delight as he wolfed them down.

In exchange, my father took such items as head cheese from Missouri to Wisconsin. The first time he took head cheese, one of my aunts, thinking head cheese was a form of dairy product, ate some with relish and then, when told it was a mixture of hog brains, seasoning, etc., became violently ill.

My father’s penchant for adulterating pure cultures is what led him to take a stick of tobacco from Missouri to Wisconsin.

It was home-grown burley. My grandfather in Missouri had planted the tiny seeds early in the spring. He nurtured them through adolescence under cheesecloth, dug the plants, separated them, punched them in with a dibble, hand-hoed them, suckered them, picked off the tobacco worms, batted the mature moths out of the air with a flat paddle, like Hank Greenberg hitting home runs, cut the stalks and hung them in the barn to cure, stripped the leaves and twisted them onto a stick which had been in our trunk when we pulled into Birch Lake on our summer vacation.

My father hung the stick of tobacco in Grandma’s shed and we all forgot about it. That is, we all forgot about it except me, and I remembered it the next day as my cousins, Hal and Frank, and I were walking down the roadside ditch toward my grandmother’s house. We had just suffered with Mr. Ken Maynard through a particularily hazardous plains epic.

“I bet you guys couldn’t guess in a million years what my dad brought up to grandma’s,” I challenged.

“Some more of them hog guts?” asked Frank in disgust. It was his mother who had become ill after eating the head cheese.

“That wasn’t hog guts,” I said. “And that isn’t even close.”

“Guess, guess, guess!” Hal exclaimed. “We always got to guess. Maybe we don’t even care.”

The Heist

“Okay,” I said, shrugging. “If you don’t care.”

“If you don’t tell,” Hal said, “I’m going to introduce you to my knuckles.” He gave me a look that would cure warts.

“Tobacco,” I said promptly. “My dad brought a big bunch of home grown tobacco from my grandpa’s house down in Missouri. Bet you guys wouldn’t smoke that stuff.”

“What’s so great about that?” Frank asked. “We tried smoking. It wasn’t all that much.”

“Yeah,” I sneered. “But that was just cigarettes. Anybody can smoke cigarettes. My dad says this stuff will blow your sinuses halfway across the room.”

“There ain’t nothing I wouldn’t smoke,” declared Hal. “Bring on your rusty old tobacco.”

We split up for lunch and promised to meet by the highway department storage shed at 1 o’clock. The garage was a wondrous place of tar smells and huge, rusty equipment.

Right after lunch I paid a visit to the shed where the tobacco was hanging. I cast a quick glance at the house where I knew my mother and grandmother were baking. It was a scary moment. Mothers have a sixth sense which tells them when their children are doing something wrong. I was convinced my grandmother could see through walls like Superman. If she did any flying, however, it was on a broom.

I slipped into the shed like a skinny ghost. The inside was hot and I wasted no time in filching a twist of tobacco off the stick. I held it behind me and peeked out the door. No one. I eased outside, hiding the tobacco with my body. Once in the weeds at the end of the lot, I breathed more easily.

I followed the railroad tracks until I was safely out of sight of the house, then cut back toward town and the garage. Hal and Frank already were there, waiting impatiently.

“I got some matches,” Hal said, showing a handful of the big old kitchen matches which popped like firecrackers when you lit them. Frank had nipped some cigarette papers somewhere.

“We better not smoke here,” Frank said. “We might get caught.”

“Where can we go?” I asked.

“Let’s go out toward the city dump,” Hal suggested, ever the planner and leader. “There ain’t likely to be many people out there.”

The suggestion had merit as long as we stayed upwind of the dump which, in those days before emphasis on civic sanitation, wasn’t exactly a field of phlox. If high heaven was straight up, then the dump smelled to there, for it was located in an old gravel pit about a half mile from town and the smell generally rose straight in the air. It was enough to bring down passing airplanes.

We followed the tracks toward the dump which abutted them in a patch of dense forest.

Up in Smoke

When we got to the dump, we found the wind blowing up and across the tracks.

“Whooey!” Hal exclaimed. “That’s enough to stink a dog off a gut wagon!” It was a phrase he had picked up from Uncle Al, an earthy type. I hadn’t heard it and whooped with laughter. Hal looked pleased.

We left the tracks, slithered down the embankment, and followed a dim trail through the woods around the dump until we had ourselves between the wind and the garbage. We tumbled into a pleasant little woodland glen, safe from prying eyes.

“Come on,” Frank said impatiently. “Get the tobacco out.” I brought out the twist and we started crumbling the brown leaves into our cigarette papers, spilling about three times as much as we salvaged.

Hal demonstrated how to roll a cigarette. It was a feat he had learned by watching the bad guys in the Saturday Western matinees. There was about an inch of usable cigarette when he finished. It had little long twists of paper on either end. It looked like a double-ended ladyfinger firecracker.

We finally made three cigarettes, each with a few puffs in them. We lit up. I dragged without inhaling, trying not to show that I wasn’t enjoying that wonderful smoke all the way to my heels.

A certain heady feeling, a mounting pressure in my skull, pushed out behind my eyeballs. It was as if someone was running wind sprints across my brain.

“Hey,” I said. “That’s really great, isn’t it?” I was as enthusiastic as I would have been at an offer to have my ears amputated.

Frank was attacked by a sudden fit of coughing. He turned red and purple before our startled scrutiny. Alarmed, we pounded him on the back and looked anxiously into his watery eyes. Finally he recovered somewhat, breathing raggedly.

“I sure wouldn’t walk no mile for that stuff!” he gasped fervently.

“You already have,” I pointed out. I was feeling queasy and lightheaded and I crushed the cigarette out on the forest floor.

The Old Buck

It was then that I saw the big buck standing on the other side of the clearing looking steadily at us. His rack of velvet-covered antlers looked as big as those of an elk. His nose was startling black, his brown eyes steady and thoughtful. I thought I was seeing things. I thought the cigarette had brewed up an hallucination. But then I realized there really was an enormous, unafraid and wild deer within 20 feet of me.

I grabbed for the other two, trying to hush them so they wouldn’t frighten the deer. But there was no danger of that. Obviously the buck knew we were no enemy of his—at least nothing he couldn’t handle with one hoof tied behind him. He was a whole lot more calm than I was.

Paralyzed with wonder, we watched as the deer advanced across the clearing. He kept one eye on us, alert for any sudden move. He whistled noisily through his nostrils. With no hesitation, the buck picked up my twist of tobacco and chewed off a big chunk of it. He munched blissfully on it as my mouth fell open.

I was so astounded at the sheer effrontery of the animal that I jumped up and shouted, “Hey! You dumb deer!” The buck wheeled and sprang easily to the other side of the clearing, then turned and looked back at me.

The deer had looked as big as a buffalo. He didn’t remind me at all of Bambi—more like King Kong.

I picked up the mangled tobacco twist and looked fearfully at it. I had a sudden vision of the tobacco poisoning the deer, then the game warden finding out how the deer had died and tracing the whole thing back to me. I didn’t know until years later that deer easily can become addicted to the taste of tobacco and will go to extraordinary lengths to get it.

The buck pawed the ground and snorted, then tossed his antlers at us. He acted peeved—no, more than that. Pugnacious.

For the first time, I began to be a little apprehensive. Maybe the tobacco had made him crazy. The deer looked piercingly at the tobacco I was holding. It appeared that he regarded it as his property and was prepared to fight for it.

Frank and Hal were holding my arms and urging me to go. I needed time to think and didn’t have it.

“Cummon!” Hal hissed. “That old deer looks mean!”

“Maybe he’s got rabies!” Frank whined. That really scared us. We began to edge away and the deer followed us, matching our every step. We backed all the way to the railroad embankment and up it. The deer was right behind us all the way and trotted along below us almost to the city limits before he turned and, with one last lingering look, melted into the woods.

“Whew!” Frank breathed in relief. “I thought that old buck was gonna get us!”

It was only then that I realized I still carried the hank of tobacco, and I threw it down and brushed the crumbs from my hands. I discovered I was trembling. The deer had looked as big as a buffalo. He didn’t remind me at all of Bambi—more like King Kong.

My mother thought I was coming down with something that night at supper. When my father lit a cigarette after dinner, I nearly threw up.

I went to bed early and lay there, my innards churning like the mighty Colorado. I fell asleep, but was awakened sometime in the middle of the night by an urgent need to visit the little structure located to the immediae rear of Grandma’s house.

I rose in the silence of the house and padded outside. The night was softly warm, one of those midsummer nights when the stars seem to have been taken down and polished, then put back up.

A Surprise Visitor

As I passed my grandmother’s tool shed, I noticed that the door was open. Absently I pushed it shut and heard the latch on the outside click into place. I continued on to my appointment.

On my way back to bed, I heard heavy breathing behind the closed shed door. Ghosts! I thought in terror. I sprinted for the house whining in panic. I knew something was racing after me, poised to spring on my back. I skittered through the house and dived into my bed. I trembled and shook under the covers. Eventually, when nothing followed me into the house, I fell asleep.

We were sitting at the breakfast table the next morning when we heard my grandmother shout. Most women would have screamed but my grandmother wouldn’t have screamed if Frankenstein’s creature had invaded her kitchen. She’d have swatted him in the electrodes with a frying pan.

But it was clear that something drastic was wrong in the backyard and we all raced for the door at the same time. My Uncle Al reached it first and already was galloping across the backyard when I ran out on the porch.

“What’s going on, Momma! What’s the matter?”

My grandmother was leaning against the shed door looking, for the first time since I had known her, somewhat nonplussed.

“There’s a great big buck deer in there!” she exclaimed in a tone of utter disbelief. “I think he’s eating my washing!”

Grandma Knows Best

Her absolute outrage would have been funny except for two things: First, I had an instant flash of prescience. I knew exactly how that deer had gotten in there. It had followed the faint tobacco trail to the shed and I had shut him in the preceding night. The entire story must never, never come out or I might just as well go right down to the lake and jump off the dam. And I couldn’t swim.

Second, this was my grandmother, beside whom Charles de Gaulle is a wishy-washy old woman. If she ever found out I was behind or had anything to do with the current problem, she undoubtedly would insist that my mother put me up for adoption. And I wasn’t sure my mother wouldn’t do it.

“Hold him, Momma! Let me get my gun!” Uncle Al sprinted back across the yard, colliding with my father in midsprint. They both went to earth dazed. But Uncle Al, his blood lust aroused by a trapped deer, scrambled to his feet and pounded into the house.

He was back in a flash, his old Winchester in one hand, a handful of coppery bullets in the other. He dropped them all over the porch in his haste to jam them into the loading gate on the side of the receiver.

“Hold him, Momma!” he shouted again. Uncle Al pursued deer with religious fervor. Normally he abided reasonably well by the laws. Had he met a deer in the woods out of season, he would have passed in peace. But never before had a deer come right up to his house begging to be taken. It was too much for him.

Feverishly he levered a shell into the chamber and raced across the yard. “Move aside, Momma! I’ll let him out and we’ll drop him!”

“Don’t shoot him!” I yelled at the top of my voice, stung by an impulse which I regretted instantly. So loudly had I shouted that everyone stopped in his tracks. My uncle turned, thinking momentarily that I was the game warden.

As all eyes turned on me, I felt I had to make some explanation and I sealed my destiny by saying, “He’s just eating the tobacco. I mean, he doesn’t. …” Here I faltered and ground to a halt, like a cheap clock.

I could see my grandmother’s face, something like that of Theodore Roosevelt on Mt. Rushmore, only not as pleasant. Storm clouds played around her granite brow. She looked across the yard at me and for a single dreadful instant I felt her zoom telescopically at me, looming to Olympian size with terrifying speed. All I could see was her flinty, uncompromising face as big as the Lincoln Memorial, an expression of Utter Comprehension flickering across it like heat lightning.

She knew! Oh, God! She knew I was behind the whole thing. She began a steady march across the yard toward where my mother and I stood. I seemed to hear rolling drums. I wanted to crouch down behind my mother’s skirt, shut my eyes and yell in fear, but I just stood there with my mouth open, my eyes like grapefruits bugging in their sockets.

Uncle Al had no time for whys. He didn’t care how the deer got there. He just wanted to get it out.

He bounded toward the shed and all hell broke loose. The buck, frenzied by fear from all the noise outside, leaped at the door, kicking at it. Just as Uncle Al reached the door, it burst open, catching him squarely in the nose. He went over backward, tears springing from his eyes. The gun exploded and there was a metallic “pang!” as the bullet went into the block of his pickup truck.

Whitetail Mayhem

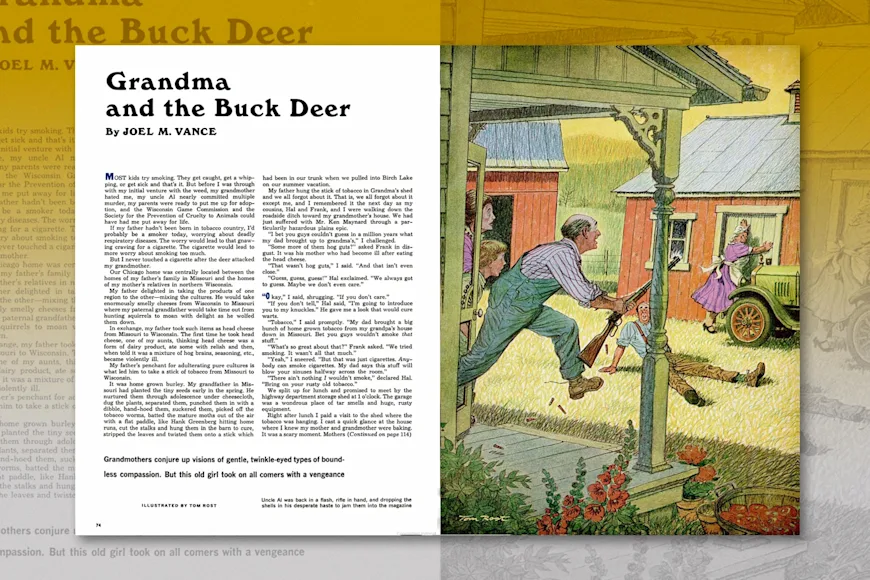

The buck charged through the open shed door, right across Uncle Al, and headed for what looked like open country. Unfortunately, my grandmother had advanced to a point precisely between the buck and what the buck considered open country. The fear-crazed animal bore down on Grandma from the rear.

Both my mother and prostrate Uncle Al shouted a warning and my grandmother turned. As she whirled, the deer reached her. With fantastic reactions for a woman of that age, she grabbed the buck by his antlers and hung on grimly. She backpedaled nimbly as the buck reared and plunged, wondering what in the name of hell had him by the horns.

I had a vision of the deer carrying her off to the woods forever. It would have solved my mounting problems.

“Leggo of him, Momma!” Uncle Al shouted. “I can’t shoot!”

“I can’t let go, you fool!” my grandmother shouted back. “The beast is crazy!”

The buck was snorting like the town mill whistle and trying to shake my determined grandmother. She held his head down so he couldn’t use his hooves and danced in front of him as he moved her along by brute strength.

Uncle Al raised his gun, aimed and then lowered it helplessly. “Ah, Momma!” he cried in anguish. “Dammit! Hold still! I can’t hit the thing with you movin’ like that!”

Even in her desperate plight, she threw him a look which would have shriveled asbestos. “I’m … not … doing … this … for … fun … you … dunce!” she grated as she jounced painfully with the tossing of the buck’s head. At that instant they passed the pickup truck and my grandmother, seeing a slender chance, let go and clambered with mountain goat agility up on the hood.

The enraged buck charged after her. As he tried to scale the hood of the Chevy, Uncle Al cut down on him. Unfortunately for the already wounded pickup, Uncle Al’s intentions were better than his aim. Another bullet ripped through the engine, laying waste to cylinders, valves, and assorted General Motors mechanisms.

“Put that gun down, you fool!” cried my grandmother. The buck, seeing he wasn’t going to get grandmother, returned to his original plan of putting a lot of distance behind him.

He headed for the front yard, bounding gracefully as only a deer can. Uncle Al raced behind him, levering another shell into the Winchester. As the deer nipped around a corner of the house, Uncle Al fired again. He missed, but the front window of the house across the street disappeared in a welter of flying glass.

Undaunted, Uncle Al chased the buck into Grandma’s front yard and shot again just as the buck leaped across the road.

The bullet thunked into a tree. The buck sailed over the blacktop just ahead of an oncoming car. The startled driver wrenched his steering wheel, jounced into the ditch, then out on the road again.

He hit a car whose driver had his entire attention fixed on Uncle Al because he thought my uncle was shooting at him. The two cars collided with a grinding crash and the drivers immediately leaped out of them and began cursing each other.

Except for the impassioned harangues of the two drivers, silence returned to the summer morning. I still stood in the backyard, dread settling over me like dust after a coal mine explosion.

The Reckoning

Everyone except my grandmother and me had followed the flow of action into the front yard. She slid down from the hood of the murdered truck and stood beside it trying to regain both her strength and her monolithic composure.

She looked up, took a deep breath that nearly cleared the yard of oxygen, and beckoned to me. It looked like the finger of the Grim Reaper. With feet of pig iron, I approached.

“How did that deer get in my shed?” she asked in a measured, reverberating voice which could easily have been coming from the sky, accompanied by flashes of lightning and boiling black clouds.

I tried to speak, but someone had sneaked into my throat and clogged it with sharp gravel. I cleared out the chat and squeaked, “I didn’t put it there.” Strictly speaking, that was true. I was evading and she knew it.

“Child, do not lie to your grandmother!” she boomed. “You do know how the deer came to be there, don’t you?”

“I’m not lying,” I stalled. I always read that grandmothers were fun, twinkly little old ladies with hearts of gold. Mine was equivalent to the bogie man-except that I wasn’t as afraid of him.

“I didn’t put him there,” I said again. “He was after the tobacco.”

My mother stepped into the periphery of my vision. “Mother, Bobby can’t be responsible …”

“Be quiet,” my grandmother ordered, not even looking at my mother. “This child knows something. If he has done something wrong, he needs to be punished.”

“I haven’t done anything wrong!” I shouted, fed up with the deer and the tobacco and every other damn thing else. It seemed that everything I did was wrong. “Why don’t you just get Uncle Al to shoot me too while he’s shooting everything else? Then you wouldn’t have to worry about me anymore!”

My grandmother’s visage settled into a mask of pure anger. That an insignificant pup like me should talk back to her was the height of insubordination. She raised a regal hand and pointed a lethal finger at me.

“Child, you are going to get the worst whipping of your life!”

True Confession

Suddenly my mother stepped between us. “Now, just a minute, Mother,” she said with steel in her voice. “I want to remind you that this is my son and if there is any disciplining to be done, his father and I will do it. You may be able to impose your will on me, but you’re not going to do it to my children. Is that clear?”

She and her mother stood locked in a struggle of will which normally my grandmother would have won hands-down. But my mother, her chick threatened, showed her heritage with an exhibition of inflexible will of her own.

It was my grandmother who cracked first. “Albert, you’d better see to your truck,” she ordered, turning to Uncle Al. “I think you shot it.”

My mother wormed the entire story out of me that night. When I finished telling her, she looked at me with something approaching awe, then with compassion. She shook her head and left the room.

Later that night, my mother and my grandmother made up.

“Mother,” I heard my mother say with, if it’s possible, a twinkle in her voice, “I think I’d like some venison for supper.”

There was a long silence. “Are you absolutely certain they didn’t switch babies on you in that hospital?” my grandmother asked. But she didn’t sound serious.

At least, I don’t think she did.

_You can find the complete F&S Classics series here

._ Or _read more F&S+

stories._