MICHELLE HAD SAID the alligator wasn’t dead, and I should’ve listened. But there was a hole right through the thing’s head from the bang stick, and we’d pulled it up onto the deck of my buddy Tom’s boat, and I’d even knelt behind it for a photo. At 8 feet long, it wasn’t a particularly big gator, but it was a decent one for public water and bowfishing gear, and my first one to boot.

I told Michelle that the writhing tail was to be expected from a fresh-killed reptile. I’ve cleaned plenty of snapping turtles in my day, after all, and you can expect them to kick for an hour, even with their heads hacked off and tossed in a bucket. That this gator was reflexing didn’t concern me much. We reloaded the Excalibur crossbow with another barbed fiberglass arrow, and Tom kept shining the river ahead with his spotlight, looking for the reflection of red eyes. We had another tag to fill.

Michelle has a way of speaking to me in a loop when it’s important to her that a certain message get across. Even if I don’t accept it right away, she at least knows that I’ve heard it. Sometimes it’s aggravating, but it does work. “You guys, seriously, that f**king alligator is still alive!” she yelled. She and Ashley, Tom’s wife, had both climbed up onto the center console of Tom’s boat, and when I panned the beam of my headlamp back toward the bow, the gator was sure enough standing on four legs, with good clearance between its belly and the fiberglass, staring up at us.

“Tom, that f**king gator is still alive!” I said.

Canned Gator

So, yeah, our alligator hunt had become a bit of a Southern rodeo, but it’s not always like that. In fact, compared to what you see on TV, most of the alligator hunting I’ve done has been pretty anticlimactic. It’s fun, and there is always the chance of a gator clamping down on a foot or a hand and causing a real mess, but the chaos is usually controlled.

It’s not particularly difficult to kill a gator of immense size, either, but it can be expensive. Though there are some genuine giants lurking in wild public swamps, a good many of the beasts you see slain by happy hunters on the Internet come from private land, and a fair number of those come from alligator farms, which raise gators from hatchlings for the commercial market. (Think leather goods, fried gator tail, and those alligator heads for sale at roadside souvenir shops.) Some farms make big money by selling their biggest gators to paying customers who want to shoot them.

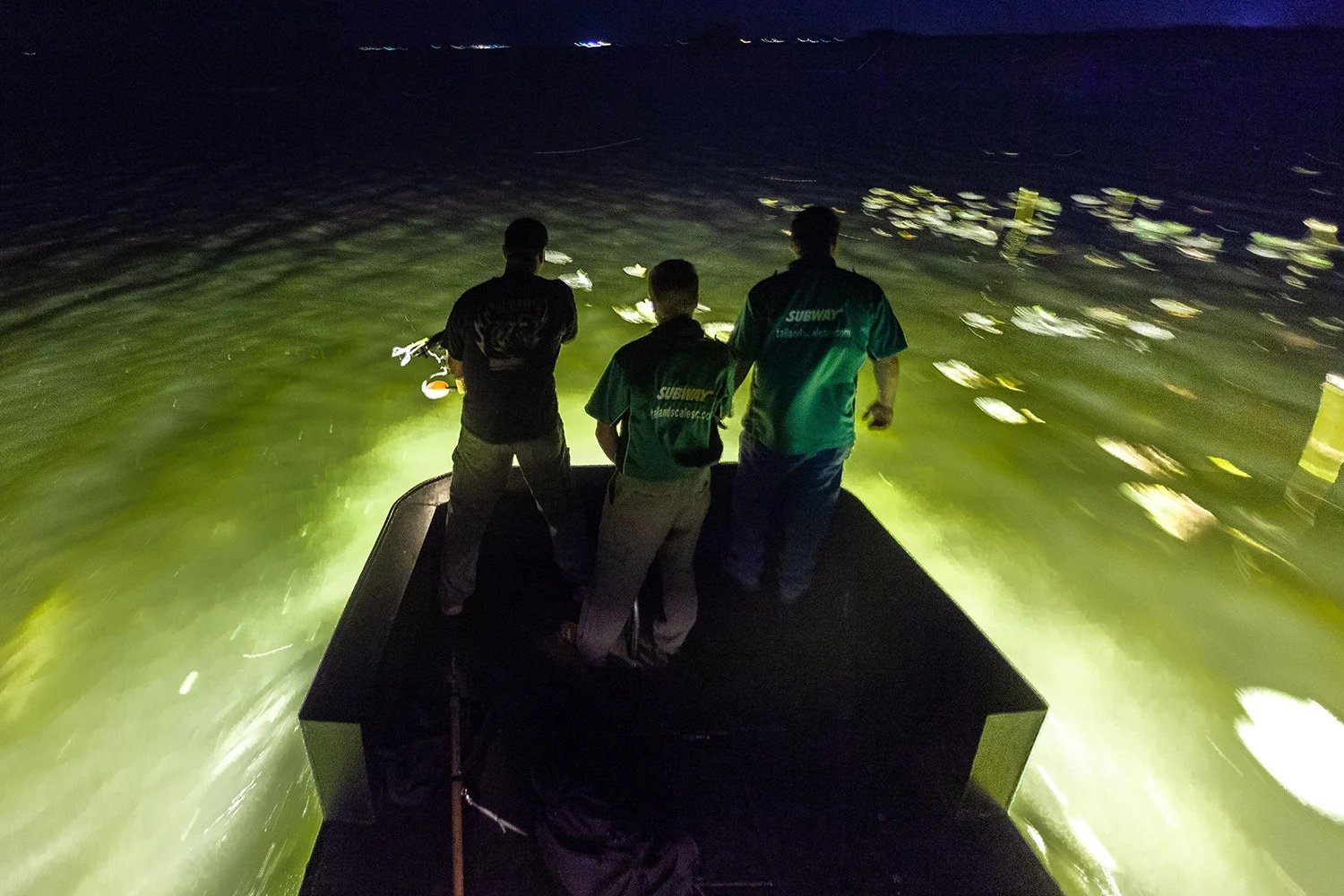

Public-land hunting for wild alligators is usually done at night, with the aid of spotlights. Richard Ellis / Alamy

Depending on the state, the gators in such places are private property and rarely subject to the same seasons or equipment restrictions as the wild alligators living in public waters. So if you see a picture of a hunter with a rifle in hand, posing next to a giant alligator, particularly from Florida, odds are very high it was a private-land hunt. Not that such hunts can’t be a good time, or are completely canned. Some of those gator farms are hundreds of acres, and seeing a giant gator that lives under the water is never a guarantee.

But traditional hunts for wild gators are much more challenging—and fun in my opinion. States including South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Florida, Mississippi, Louisiana, Arkansas, and Texas all have alligator seasons that generally open in late August or early September and run for a few weeks to a month or longer (Florida’s season goes to November 1). State alligator harvests are typically set by quotas and zones, and permits are issued via lottery, like many Western big-game permits. The permit holder doesn’t always have to be the one who kills the gator; they just have to be on the boat and helping with the process.

Hunting is usually done at night (Louisiana is a notable exception), with the aid of spotlights. Alligators are caught with snares, harpoons, big treble hooks at the end of a line, or with heavy bowfishing equipment rigged to buoys. The gators are dispatched at the side of the boat with either a bang stick or a firearm (states that allow firearms often limit the options to handguns).

We’d looked over several little alligators that night on Tom’s boat before drifting into crossbow range of the one I shot, which was suspended just beneath the surface at the end of a logjam. The bowfishing arrow hit him solidly in the side, and we fought him to the surface with braided line affixed to a large buoy. Tom then snagged him with a treble hook on a saltwater fishing rod, and eventually, we wrestled the thing boat side where we thought we’d killed him dead.

Taped Shut

An alligator’s downward bite pressure is said to be one of the strongest on the planet, at about 2,000 pounds per square inch, but its ability to open its jaws is comparatively puny. That’s why many alligator hunters tape the jaws of dispatched gators closed with several wraps of good duct tape. Tom and I should’ve done just that, but we didn’t. When the gator resurrected itself, Tom jumped on its back, grasped its jaws closed with his hands, and wrestled the front end of the critter over the gunwale. “Grab his tail or we’re going to lose him!” he yelled.

I bear-hugged the gator just in front of the hind legs and decided he was way more alive than I’d given him credit for, with most of the brain activity being concentrated in his thrashing tail. Tom reached for the bang stick and eventually put another bullet into the reptile’s head.

“This alligator is dead now,” he said, pulling the thing back onto the deck of the boat, “but I think I’ll tape his mouth up just to be on the safe side.”

_Read more F&S+

stories._