On October 2, an elk hunter was attacked near Fort Steele, a community in southern British Columbia near the border of Montana. According to a press release from B.C. game wardens, the attack involved a sow grizzly bear with cubs. The hunter, sixty-three-year-old Joe Pendry, has since died from injuries sustained during the attack.

Pendry was chasing elk in B.C.'s East Kootenay area when the attack occurred. In its press release, the B.C. Conservation Service said the grizzly was drawn in by his elk calling. Pendry fired one shot in self defense, which eventually killed the bear, though it wasn't found until October 17.

Mark Hall, a resident of the neighboring town of Cranbrook and the executive director of Wild Origins Canada, says the on attack on Pendry is one of the most severe in the area in recent memory. “It is one of the worst attacks I’ve heard of,” says Hall. “This area is a mecca for grizzly bears, and at the same time, a lot of people wanting to recreate and hunt.”

Hall says one of the reasons grizzlies are so prolific in the Columbia Valley is the species’ utilization of kokanee salmon that run up the Kootenay River system. That food source and good riparian habitat has led to an anecdotal increase of human-bear encounters in recent years in the area.

While human-bear conflicts are common in Columbia Valley and neighboring Elk Valley, they’re not confined to Southeast British Columbia. On October 12, two hikers were attacked by a grizzly bear near Prince George; both were airlifted for medical help, with one being in critical condition. Overall, recent years have shown a marked increase in calls reporting human-grizzly bear conflicts in the province.

Broader Grizzly Bear Issues in B.C.

Grizzly bear management has been a hot topic in local communities in British Columbia for several years now. In 2017, the provincial government instituted a hunting ban for the species for political purposes—not ecological reasons, Hall says.

“British Columbia is like California,” he adds. “Eighty percent of the population is in Vancouver and its outlying areas. It’s urban, not tied to hunting, and not tied to having to live with large, dangerous predators nearby. There’s just something in the water on the West Coast.”

While recent attacks have prompted some calls to return hunting to the province, largely from folks in less urban areas, Hall says it’s unlikely this will happen given the current political situation. He adds that even when hunting was allowed in the area, the tag allocation was so conservative that it was unlikely to have a significant effect on the grizzly bear population—or on bear behavior. Still, Hall notes that the hunting ban has had unintended consequences on bear management.

“When we had the hunt, populations were closely monitored,” he says. “But after they took hunting away, monitoring has seemed to drop off.”

He says that well-funded, anti-hunting groups have a strangle hold on bear management lobbying in the province, which prompted him to launch “Project Grizzly Balance,” an initiative that intends to “restore ecological and social balance by promoting respectful and sustainable management of grizzly bears.”

“There has to be some sort of a balance,” he says. “Our mission is to have rural people's voices heard and to get a greater segment of the population to understand that there is a place for sustainable-use hunting of grizzly bears in a respectful way that can meet both conservation and human-safety objectives.”

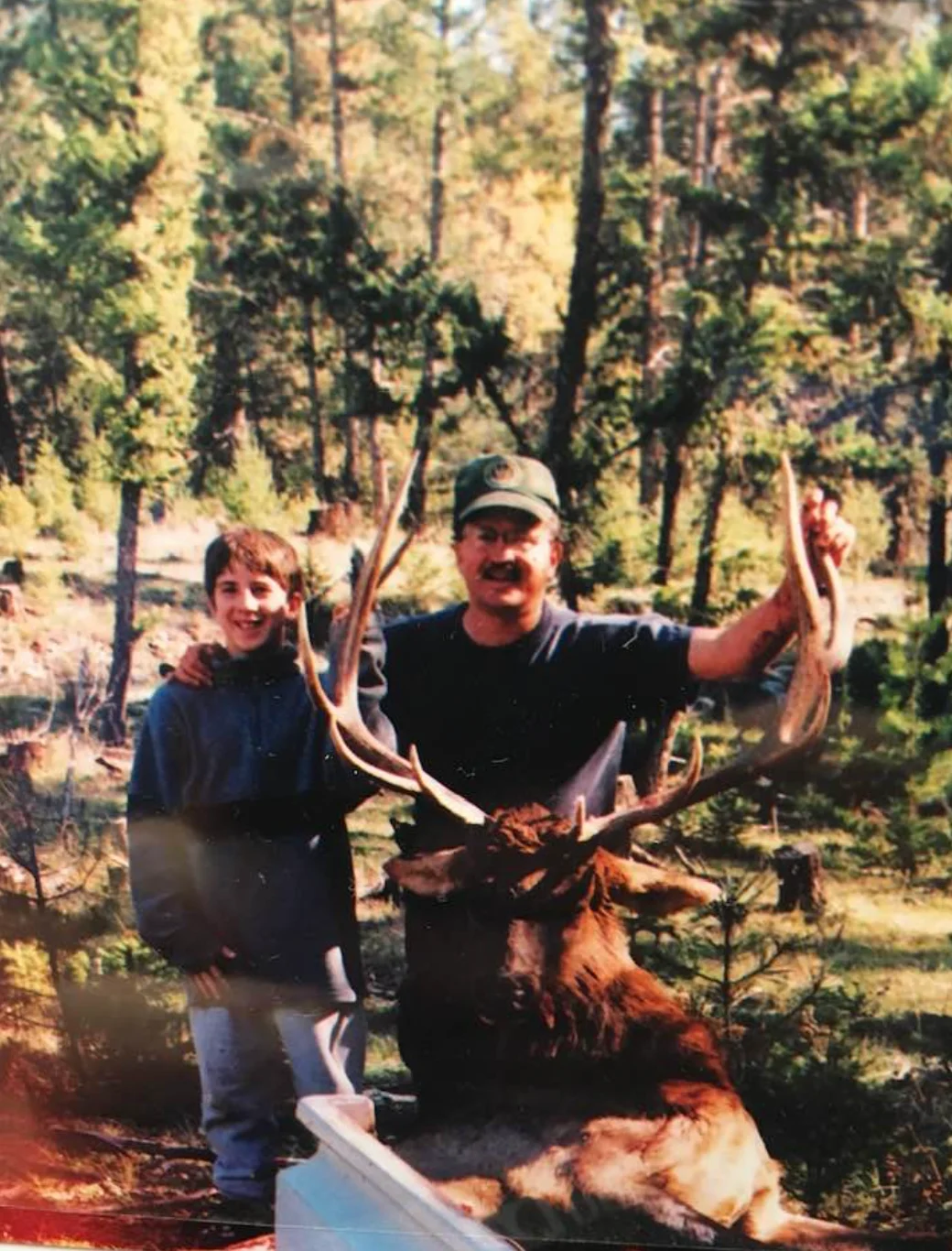

In a GoFundMe post set up to help pay Pendry's hospital bills his friend Wayne Wright said he was recovering well on October 11. Sadly, the situation took a turn for the worse on October 25, when he went into cardiac arrest from complications association with a blood clot. "I can’t thank everyone enough for all your continued love & support for my Dad and our family over the last 3 weeks," said Pendry's daughter Janessa Higgerty, in a recent Facebook post. "We will need time and space to process and grieve."