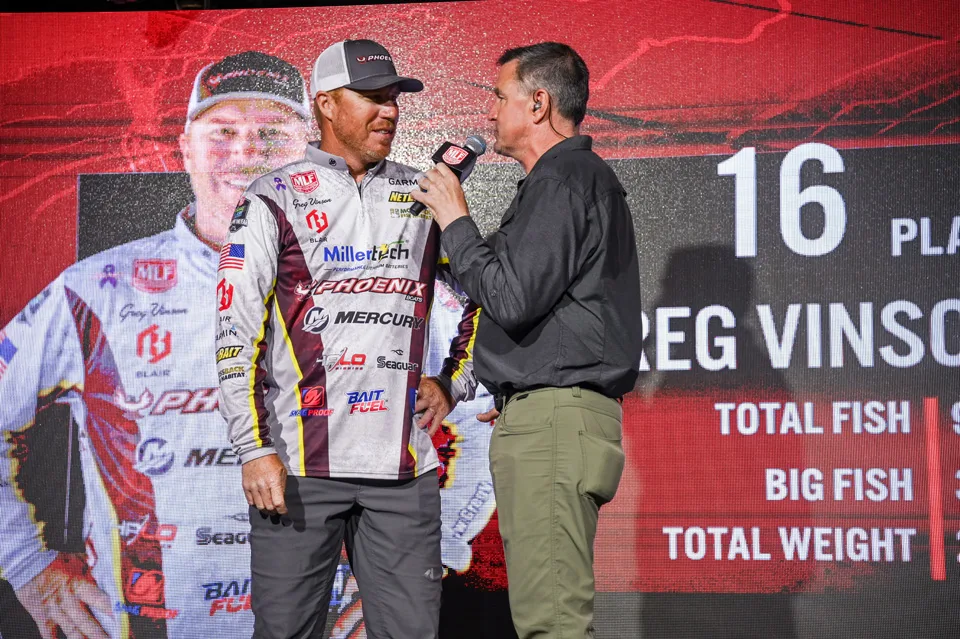

Every year, bass anglers struggle with the fall turnover. As the nightly lows begin to drop, the water's surface layer cools. The colder water on top becomes denser and heavier than the warmer water beneath it, and in a moment, the lake turns over. When the water columns swap, they stir up sediment and deplete oxygen levels. All of this can shut off the bite, making it hard to catch fish for several days. To help you navigate the turnover, we sat down with MLF Pro and environmental scientist Greg Vinson to learn more about this annual event and how to beat it.

What is the Thermocline and Why Does it Matter?

Understanding the fall turnover starts with the thermocline. This is a thin layer of water that separates the cold water beneath from the warmer water above. “The water gets layered, starting in the spring, and it goes through October," says Vinson. "You’ve got a warmer, more oxygenated surface layer, and then you have a thermocline. Most importantly, below the thermocline, there’s very little oxygen. That area is not favorable to fish."

Vinson recalled sampling water on Smith Lake and Lake Martin in his home state of Alabama and found the thermocline to be around 40 feet deep at its deepest point. These are two very clear lakes. The thermocline is much shallower in stained and muddy fisheries, where the sunlight can’t penetrate as far. Regardless of how deep the thermocline is, there won't be any algae growth–and therefore oxygen production–any deeper than light can penetrate.

What Triggers the Turnover?

Anything from a few cold nights to a tropical system dumping torrential rain can be enough to trigger a turnover. Essentially, as soon as the surface temps cool and become colder than the water beneath, the water turns over.

“There's a lot of organic matter that gets mixed at that thermocline," says Vinson. "That’s why when you see a full-tilt turnover, the water will have an odd color to it and you may see a little debris.” Looking for this brownish tint to the water will help you identify the areas of a lake that are turning over. It’s important to note that not every area of a fishery will turn over simultaneously. “Shallow water can turn over quickly," Vinson explains. "Often, a creek or large bay will turn over before other parts of the fishery."

If the turnover is due to a couple of super-cold nights, the system can recalibrate in a couple of days. Sometimes, though, the turnover can be drawn out, and it may take a week for things to return to normal. While this is happening, the fishing can be extremely tough. But there are still ways to catch bass.

How to Beat the Fall Turnover

Remember, an entire fishery doesn't typically turn over all at once. Look for cues, like the off-color water, and if you see them, consider targeting different areas. “If I get in an area and I'm seeing clues like lethargic, unresponsive fish, the first thing I do is change sections of the lake.”

If a large rain caused the turnover, Vinson recommends heading to the back of the creeks. Fish often migrate to moving water because it's well-oxygenated. The more current you’ve got, the more the water is mixed and the less of an impact the thermocline can have. Focusing on baitfish is key throughout the fall, but especially when trying to dodge a turnover. Use your graph to locate bait below or look for bait along the surface and focus on these areas.

“Sometimes it's just as simple as finding the food source because they're susceptible to all the same things that the bass and every other fish are," says Vinson. "If you're seeing a lot of bait, odds are you're in a good area." Vinson recommends grabbing a search bait and covering as much water as you can. “This time of year, fish are typically dialed in on baitfish, so keep your presentations in that same range," he says. "Some of my favorites are spinnerbaits, jerkbaits, and swim jigs in shad patterns. A lot of fish are looking up that time of year, so it's a good time to throw a bait that runs near the surface.”

You can also use your electronics to help you. Vinson has found that he can actually see the thermocline using his electronics. Not only can he see it on forward-facing sonar, but also on traditional 2D sonar and down-imaging. “You’ll see a dense layer," he says. "It'll look sort of cloudy, but it'll have a distinct edge." If you're not seeing that, but the screen looks busy, there's a good chance you've already gone through a turnover.