_We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn more ›

_

Every now and then I publish figures on the average life of barrels. I get most of this information from gunsmiths who change barrels a lot, and give their best guess. But they are guesses, and that’s all they are.

A .308, I have stated, should give you 5,000 rounds of first-class accuracy. One High Master F-Class shooter whom I asked said 3,500 rounds, and a dreadful, error-filled book by a Navy SEAL sniper said 10,000, but no one I spoke with argued the 5,000 figure.

Which brings us to my .308 F-Class rifle, which I began shooting in competition in 2016, and through which I shoot about 1,000 rounds a season. All of these are fired in the heat of the summer, in strings of 22 to 25 rounds, three strings in a day, which means that after each string, the barrel gets hot enough to brand a heifer. So, at the last match of the 2019 season, my barrel had 3,500 to 4,000 rounds through it.

Barrel burn-out, when it comes, shows up suddenly. One day it’s fine, the next day you get fliers. I’ve burned out a .25/06 barrel, a 7mm Weatherby, a .280, and probably another .308. All of them followed this pattern. In the case of my F-Class gun, the barrel chose to die during a match.

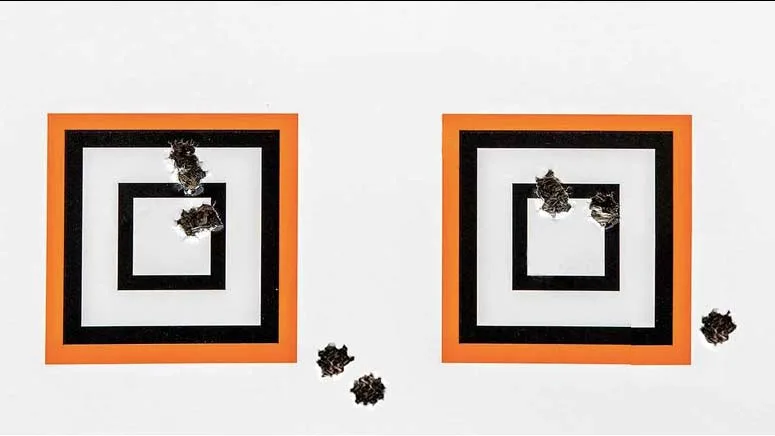

Unexplained fliers on your target are a tell-tale sign of barrel burn-out. Dave Hurteau

My first string, at 300 yards, was OK. The second string, at 500, was fine until I put two shots in the 7 ring. (To put this in perspective, if you get a 9 in F-Class, you contemplate hurting yourself. A 7 is beyond thinking.) “WTF?” I said, and put it down to a Grand Senior Tremor. (Grand Senior is my NRA age classification; it has a nice ring to it, but is otherwise pretty depressing.)

Then, at 600 yards, the same thing happened. Two shots went into the 7 ring, this time high. I accepted them philosophically and bit my adjustable comb very hard.

All four shots had looked good going away. There was no wind to speak of. The odds of four bad handloads were nil. So finally, I did what I should have done in the first place and stuck my borescope into the breech. There was no rifling left for roughly an inch ahead of the lede.

Looking up the bore from the breech with your naked eye will not tell you anything; a borescope is the only way to see the awful truth. Nor will looking from the front end do any good. Barrels burn out from the breech. The rifling at the muzzle of my match rifle shows hardly any wear at all.

Barrel life is determined by a number of things. First is the powder charge relative to the diameter of the bore. The more powder you burn, the sooner your barrel will die. A .300 Weatherby, which has a .308-diameter barrel and burns around 80 grains of powder, has about half the barrel life of a .308 that burns 40 grains.

Pressure gets into the mix. The higher your pressures, the hotter the powder flame, and the faster the steel erodes. Friction from the bullet has no effect at all. If it did, bores would burn out fastest at the muzzle where the bullet has reached its full velocity.

Stainless steel is supposed to last longer than chrome-moly, and it probably does. Deep-cut rifling and fewer lands and grooves help. (Six is standard, but during World War II, some .30/06 barrels had only two lands and grooves, and they shot fine.)

But most important is how the rifle is used. Prairie-dog-rifle barrels have short lives, as do competition rifle barrels. Some big-game-rifle barrels, which are shot only a few times a season, last nearly forever.

The intelligent shooter resigns himself to the fact that a barrel is an expendable item. I know competition shooters who buy them by the half dozen, if they get a good price, and screw a new one in every season.

Jim Carmichel, when pestered about barrel life, used to tell people: “You should have the good luck to shoot enough to burn one out.” When Jim went on a prairie-dog safari, he would pack his motor home with rifles and ammunition and end the hunt when he reached “…ten thousand rounds or half a dozen barrels.”

Melvin Forbes tells people: “Right now, Douglas [Barrels] is making new ones, whether you tell them to or not, and I can get you one in a day.” This is the correct attitude.

Most gunsmiths have a working relationship with a particular barrel maker, or several, depending on how much you want to spend. Most barrel makers offer a dizzying array of tapers, a choice of stainless or chrome-moly steel, and some offer replacement barrels for particular rifles with just about all the work done. All the gunsmith has to do is unscrew the burnt-out tube, screw in the new one, and headspace it.

Right now, there are a lot of very good barrel-makers, and a number of superlative ones. The very good guys fall in the medium-priced bracket, and the superlative ones cost money. Here is a list of makers in both price ranges whose tubes I’ve used over the years and been more than happy with: Lilja, McGowen, Douglas, Shilen, Montana, Bergara, and Schneider.

A line of freshly minted barrels at the Bergara factory. Bergara

In the end, it doesn’t matter what I say about barrel life, or what anyone else says. When yours is burnt out, it’s burnt out, and you can be served notice at the worst possible time. I found out in a match, and it cost me points that I could not afford to lose. If you’re a hunter, the burnout may announce itself by a bullet sailing over the back or under the chest of an animal you’ve worked your butt off for.

Watch your targets. Fliers that have no obvious explanation may mean it’s time to play Taps for that tube and go to the gunsmith.