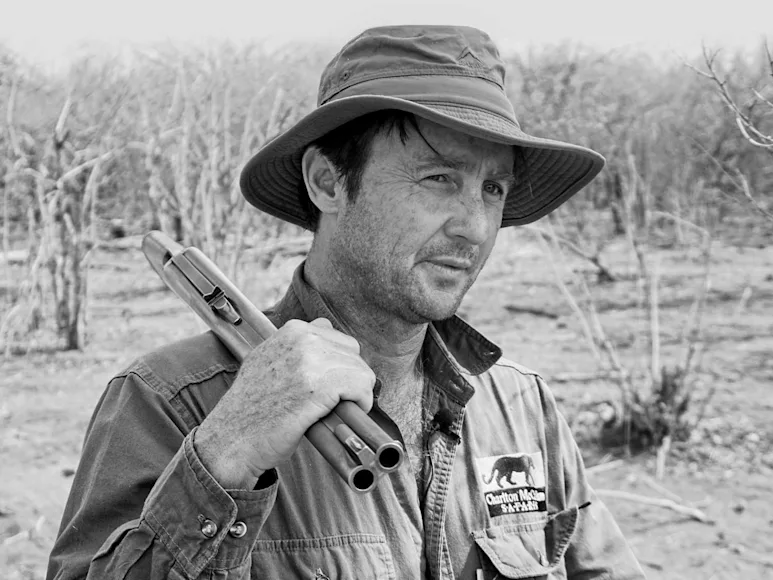

I met Buzz Charlton in 1992, on a safari in Zimbabwe when he was a 19-year-old apprentice PH. Buzz’s father was a professional hunter in Kenya, and Buzz has hunted since he was a boy. He has survived attacks by hippo, mamba, and elephant, and has kept both his life and his sense of humor.

On a safari in 2017, he managed to listen to two weeks’ of my “safaris in the good old days” stories without going mad. Buzz is the author of Tall Tales—the Life of a Professional Hunter in the Zambesi Valley_._ He operates C-M Safaris with his lifelong friend, Myles McCallum.

Q: What’s the most important quality a PH can have?

A: Well, the typical day is 16 hours, most of which is one-on-one with the client. That’s far more time than I spend with my wife. You need great people skills.

Q: What about the client?

A: He needs a sense of humor and flexibility. If you’re after an elephant and you get news that there’s a hell of a buffalo around, it’s buffalo time.

Q: Have you ever thought, This time, I really am going to die?

A: I’ve been in two squashings by elephant, two clawings by leopard, and dozens of charges by all of the Dangerous Four. In the moment, you’re too focused on the job at hand to think about getting killed. It’s afterward that you realize how dangerous it was.

Q: Which was the worst?

A: The elephant squashings. Oddly, both had happy endings. In the first, my tracker had his pelvis pulverized. But after a lengthy stay in hospital, he immediately impregnated his two wives, which he’d been struggling with for years. In the second, a French client had six ribs broken and a lung collapsed. But the doctor discovered a blocked artery, and he ultimately had a triple heart bypass. So that elephant stomping indirectly saved his life.

Q: What do you do when an elephant charges?

A: I used to fire a warning shot, and if the elephant continued the charge, I’d shoot it. After a few close calls with jamming rounds, I did away with the warning shot. I tell my clients that if I shoot, it’s a free-for-all.

Q: What’s the most dangerous game animal?

A: I’ll divide that into two groups: wounded and unwounded. Unwounded elephant cows, without a doubt, and wounded lions. The latter are so well camouflaged and so fast that both luck and skill are required for a happy ending. A wounded leopard has the most chance of giving you a face-lift, but in all likelihood you will survive. If a lion gets to you, it will most likely kill you.

Q: What is the most difficult dangerous-game animal to hunt?

A: Tracking lions in wilderness areas like the Zambezi Valley requires exceptional trackers and luck, but taking a big lion on foot after hours of amazing tracking is the ultimate hunt.

Q: Caliber-wise, what’s the cutoff for dangerous game?

A: For a PH, you need a rifle that shoots at least a 500-grain bullet, because when we shoot, we need to drop the animal. For a client, a .375 and up to whatever they can handle. Every person has a limit. If I shoot anything bigger than a .500, I start flinching.

Q: What’s the most common mistake first-time clients make?

A: Focusing on the big, glamorous animals and turning down the little trophies like duikers and grysbok. After a few safaris, they see the light.

Q: You say it takes luck to get out of some scrapes. Do you ever think, I’d better quit before my luck runs out?

A: No. As a matter of fact, the older I get, the luckier I’m becoming.

This story originally appeared in the December 2019-January 2020 issue of Field & Stream.