_We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn more ›

_

IT’S TRUE that they don’t make stuff like they used to. But even if they did, there are some tried-and-true classics—like Dad’s pocketknife or that lucky bass plug—that we would keep right on using anyway. We asked our best writers to pick their go-to vintage outdoor gear, stuff they still use on the water or in the field or marsh despite their being modern alternatives. Here are the 14 items they chose, and why these classics remain such favorites.

1. An Imperfect Imposter

The author bought this handcarved mallard decoy at an antique shop. Nick Cabrera

By the time I was born, my dad had a small but beautiful collection of antique duck decoys. I was fascinated by them—by the marks their makers had left and by the idea of turning wood and paint into something that could seem alive. Yet not perfectly lifelike. A handcarved decoy is more the carver’s idea or memory of a duck than an anatomical copy. It’s in the places where he or she misrepresents the real bird that you get a glimpse of who the carver is as an artist.

One day, I would like to hunt over a decoy spread that I carved myself—and then leave it to bang around in antique shops and flea markets after I’m gone. But for now, I’ve added this handcarved impostor I bought at an antique store to my rig of plastic mallards. It’s made of cork with a wooden head and has the former owner’s initials burned into the keel. On slow days, when the birds aren’t flying, I like to watch it bob in the marsh and imagine the hunts it’s seen with its beady glass eyes. —Matthew Every

2. True North

The baseplate compass was invented roughly a century ago and still belongs in every backcountry pack. Polly Becker

Gunnar Tillander knew that north was north and you really couldn’t change that, but there had to be a better way to figure out how to get there. In the late 1920s, the Swede invented the baseplate, or orienteering, compass. Its -liquid-damped capsule allowed the compass needle to settle quickly and stay in position even when the compass was held in the hand and on the move, and the rotating bevel affixed to a clear plastic base enabled the device to be placed on a map without blocking the view of all those elevation lines and map legends. It was pretty rad at the time, and when Tillander and three other Swedes formed Silva

in 1932, staying found got quite a bit easier. Even in the era of GPS and onX, I stash this compass in a shirt pocket for quick reference in the woods. There’s something about that magnetized needle settling northward with authority that makes me feel as if I know where I am and where I’m going. —T. Edward Nickens

3. The Deer Cartridge

The .30/30 has been around so long, and will remain in use, because it works. Polly Becker

Growing up, I had an aversion to the .30/30 Winchester because it was older than the old-timers at our deer camp who used it. They all said, “He’ll learn.” And they were right. I have since used it from the hardwood hills of the Alleghenies to the African veldt.

Unlike the .223, .308, .30/06, and .45/70, the .30/30 didn’t achieve legendary status in war. It earned its reputation in the hands of hunters. As our first smokeless centerfire cartridge, it was more or less the Creedmoor of its day, and though no one would call it flat-shooting by modern standards, its light recoil, moderate velocity, and big bullet still make it a solid choice for big game worldwide. It’s been used to take bears, moose, elk, and African lions, but as a deer cartridge, it is the American classic.

It’s been 126 years since the .30/30 was introduced, but you’ll still find rounds lying in the center consoles of folks’ trucks, jingling in the jeans pockets of serious hunters, and for sale in dated boxes at mom-and-pop general stores. And you may well find them for another century plus. Because they work. —Richard Mann

4. A Reel Bargain

The author’s Pflueger Medalist cost him all of $10. Nick Cabrera

I’d never wanted to try fly fishing. But then, about four years ago, I was at an auction, and a bramble of fishing rods wrapped in monofilament came across the block. The auctioneer started the bidding at $50 and quickly dropped to $30, then $20. When he got to $10, my hand shot up reflexively, and I won the tangled mess.

I spent the rest of the night unraveling my prize. Just about all of the rods and reels were junk. But in a rat’s nest of sunburned line, there was an old Pflueger Medalist fly reel

in working order. For a year, the reel lived on my desk. I’d turn it when I talked on the phone. Then one day I bought a beginner’s fly rod on a whim, and before I knew it, I was learning how to fly fish.

I’ve bought a lot of fly-fishing gear since, but that Pflueger is still my go-to reel. It’s probably the best $10 I’ve ever spent on fishing. Though, come to think of it, I could’ve probably gotten it for $5. —M.E.

5. Go-To Glass

The author’s vintage Zeiss binocular has served him for decades. Polly Becker

In 1985, while roaming the aisles in Orvis’ first New York City store, I noticed a Zeiss binocular

for sale at a price so low it could only be described as deranged. It was an 8x30B T*, which was the top of the line. Orvis could not move it, and the store wanted it gone.

I didn’t need another binocular, but I bought it anyway, and in the intervening 36 years I have used it more than any other glass by a very wide margin. It’s compact, but it’s not light. It does not compute range, measure wind speed, take home a GPS. All it will do is give you a good look at whatever you want to see. It has done this under all conditions of light, weather, and anything else you can conjure up. It’s as solid and tight as the day I bought it.

I expect the glass will continue to perform until the end of my hunting days, and then it will do as well for someone else. If mein alter Zeiss is not a classic, then there is no such thing. —David E. Petzal

6. The Ubiquitous Blade

More than 100 million Rapala-Marttiini fillet knives have been sold. Nick Cabrera

Stuffed in the bottoms of tackle boxes the world over, beneath the battered black Jitterbugs and rusty metal fish stringers, lies one of the most recognizable blades in the world: the Rapala -Marttiini fillet knife

. I’ve owned, lost, and given away at least half a dozen of them.

By the late 1960s, when the knife debuted, the name -Rapala was already a fishing fixture. The company’s first plug was whittled from cork and covered with shiny foil from a candy bar. It was simple and effective—the two main characteristics Rapala wanted in its fillet knife. In 1967, the company got legendary Finnish knife maker Janne Marttiini on board to craft a flexible -stainless steel blade affixed to a chunky, fist--filling handle. The blade slipped around and over fish bones with ease. The classic birch handle stuck to slick, wet hands. It was inexpensive but had an Old World feel. And it flew off the shelves. More than 100 million have been sold, in various iterations. I’ve used my current one on 6-inch bluegills and slot redfish alike. For less than $30, you can afford to lose one; you just can’t afford not to replace it. —T.E.N.

7. The Coolest Camo

Winona Camo was around long before Trebark, Realtree, or Mossy Oak made the scene. Polly Becker

I’ll have you know that I was wearing Winona before it was cool. Wait, you didn’t know it was cool? Well, you remember the iconic sweater worn by the Dude in The Big Lebowski, right? That sweater was manufactured at the Winona Knitting Mills, the same place that produced my go-to treestand jacket. For years, Winona made some of the best-looking, quietest, most effective camouflage clothing you could buy.

Accomplished Minnesota bowhunter Bob Fratzke had been an employee of the knitting mills since his high school days when he recognized the need for silent, durable hunting clothes with a high-contrast pattern to help bowhunters blend in. Fratzke’s Winona Camo hit the market in 1975, a full five years before Trebark and more than a decade ahead of Realtree and Mossy Oak.

While Fratzke never had the marketing or production savvy of those camouflage giants, Winona Camo held its own for many years, and can still be found online

if you look, thanks to a committed band of loyal followers. And because it’s so cool. —S.B.

8. My Original Point

Zwickey broadheads were introduced in 1938 and are still a favorite with traditional archers. Nick Cabrera

I glued my first Zwickey broadhead to a cedar shaft back in the 1980s, but they go a lot further back than that. Minnesotan Carl Zwickey introduced his original Black Diamond broadheads in 1938, and they became so popular that the company could barely keep up with demand. One of its most loyal customers was none other than Fred Bear, until he produced his own broadhead that nearly put Zwickey out of business. Zwickey kept the company alive by inventing the Judo Point, a nearly indestructible stump--shooting and small-game head. It proved so successful, Zwickey was able to keep making the Black Diamond, Eskimo, and Delta heads that have famously taken big-game animals around the globe. Aerodynamic, tough as nails, and known for holding an edge, Zwickey broadheads will be in my archery gear box, and on my recurve hunting arrows, for as long as they’re made. —Scott Bestul

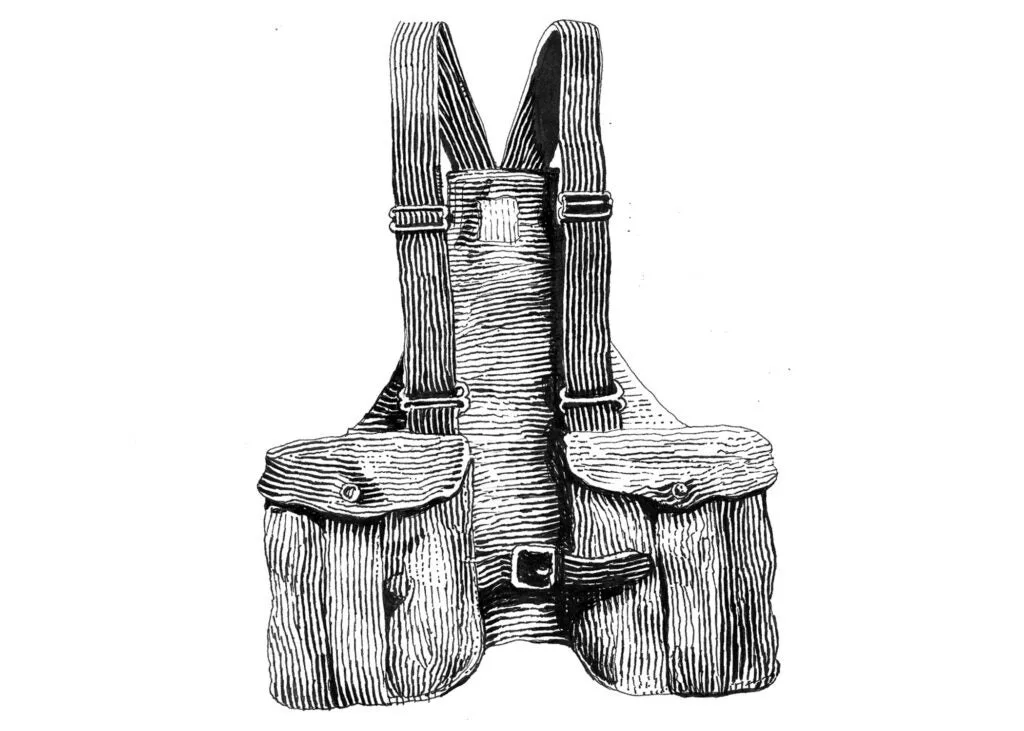

9. The Thorn Thwarter

Filson’s classic Tin Cloth Game Bag is tough as nails and looks good too. Polly Becker

Some people looking at my bird vest probably think it needs an oil change. It doesn’t need a thing—not a weight-distributing yoke or a hydration-bag pocket or anything else you might get with today’s high-tech models. The material is the same as Filson’s old No. 32 Hunting Vest

developed in the early 1930s, a wax- and oil--saturated canvas duck that knocks back briars and thorns, stays dry on dewy mornings, and lends authority and gravitas in the bargain. When my day calls for a bunch of in-and-out-of-the-truck quick hits as I bounce from cover to cover, this classic Tin Cloth Game Bag is just the thing. There’s a rear-loading game pouch. Each expandable shell pocket holds a box of shells. The shoulder straps are adjustable. A bridle-leather waist strap holds it closed. And that’s it. If you really have to have 32 ounces of water, there’s a cooler in the truck. This is bird hunting, for goodness’ sake. It’s supposed to be simple—not to mention stylish. —T.E.N.

10. Buff Boots

The African P.H.’s go-to hunting boot. Nick Cabrera

are handmade from native African animal skins in a small shop in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. They’ve become a status symbol for highfalutin debutante safari types who want to prove their bona fides by wearing the same footwear as their professional hunter. The boots are not cheap, and I ignored them for more than a dozen safaris as I watched other name-brand boots disintegrate on my feet while I trekked across the veldt. Then my son bought a pair after his third safari, and I tried them. I felt like a fool for not doing so sooner. They are extremely comfortable, handsome enough for a night on the town, and rugged enough for the most ragged country you can cover on foot. Made from buffalo, kudu, ostrich, and hippo hides in the veldschoen (from the Dutch for “field shoe”) method, Courteneys mold to your feet. Wear them for one day and you’ll understand why they’ve been the gold standard in international hunting footwear for decades. —R.M.

11. The Camp Cooker

A Dutch oven with spider legs lets you easily pack coals underneath. Polly Becker

I don’t know why it took me so long to land a spider-legged Dutch oven, but for years I used a stovetop model for cooking with coals. What a pain—and never again. Legend has it that Paul Revere came up with the idea of putting legs on the bottom of a cast-iron pot to raise a Dutch oven a few inches so coals could more easily be shoveled under-neath. That seems appropriate, because there aren’t any American cooking vessels more legendary than this.

Also called black spiders or spider pots, these were a staple of chuck--wagon and cowboy cooking. The bail handle makes it easy and safe to maneuver over a fire. The lipped lid holds coals and keeps ashes out of the grub. A small loop handle on the lid makes it easy to grasp with a Dutch oven lid lifter. Most important, those legs let a serious camp cook show off. When I’ve got many mouths to feed, I can stack multiple spider-legged Dutch ovens, with coals underneath and on top, and crank out several dishes at once. —T.E.N.

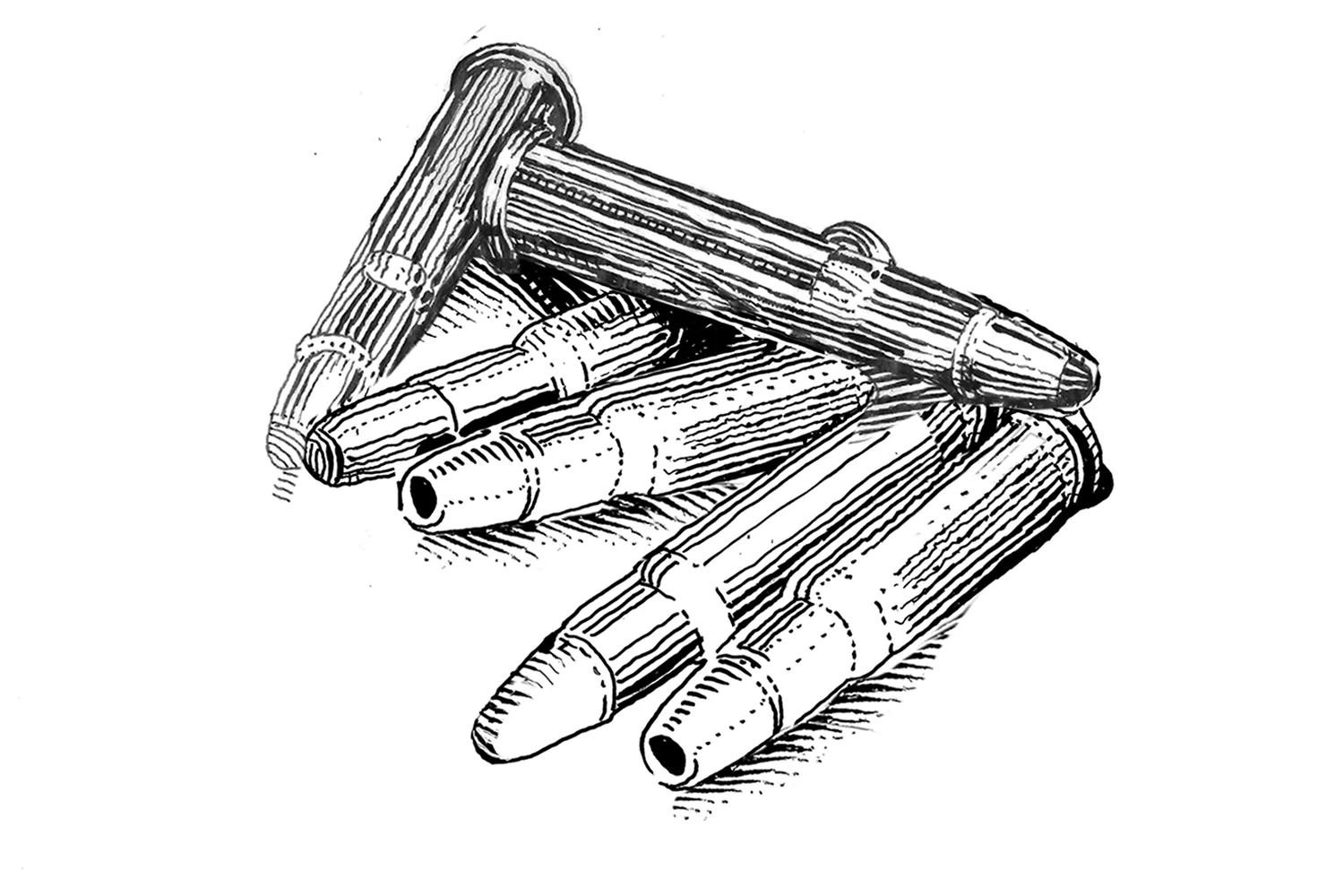

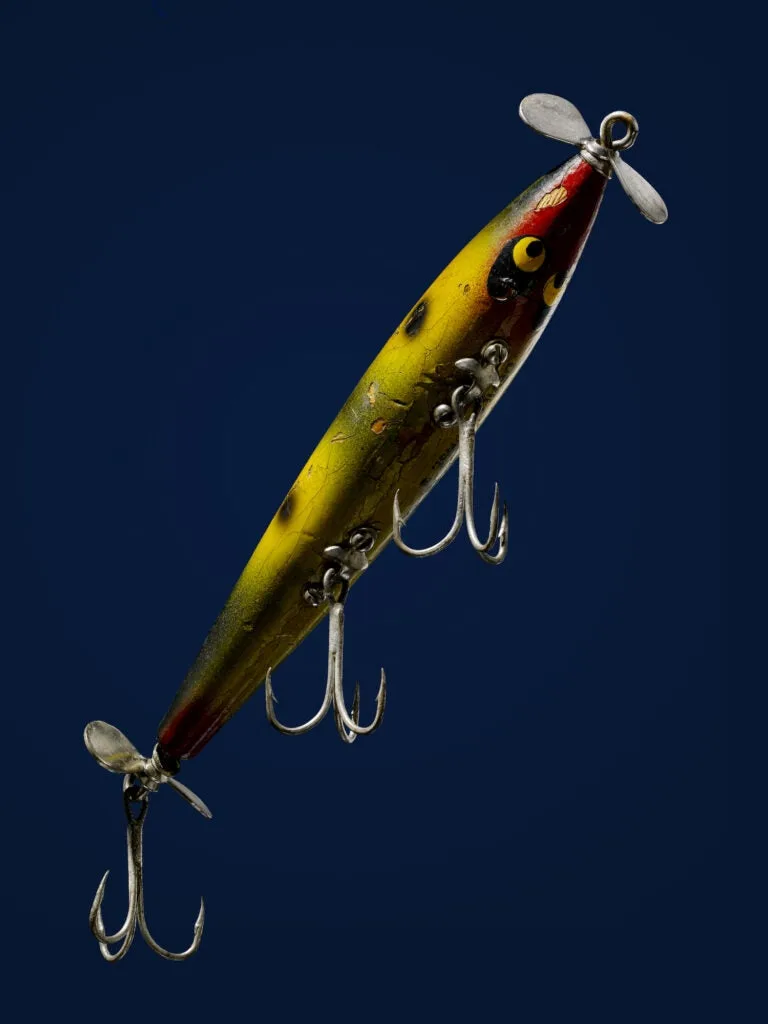

12. Props

Vintage propeller baits, like this Smithwick Devil’s Horse, still fool as many bass as ever—maybe more. Nick Cabrera

You want your bass plug to sound like a distressed minnow, not a wallowing hog. Many of the earliest topwater plugs, such as the Dowagiac Surface Minnow 300, came equipped with small fore and aft propellers that produced the most discreet of noises. The tiny pinwheels have kept on spinning for more than a century.

Given modern fishing pressure, these old and overlooked prop baits have never been more useful. Jack Smithwick’s Devil’s Horse has hit its proverbial threescore and 10, but it still goes zip-zip-zipping over bass cover. Same with Heddon’s -Dying Flutter and the Torpedo brothers, Baby and Tiny. The latter have rear props only, as does Bagley Bait’s Bang O Lure Spintail, and all are so quiet you only think you hear them. A whisper from another time. Classic prop baits can be started and stopped, retrieved slowly and steadily, or planed across the surface. The bass hear them fine. Or you can just leave them out there to fish while you relax. The propellers will continue to spin as the lure bobs on the surface, a feature the fish in the lakes near me seem to find especially appealing. —Will Ryan

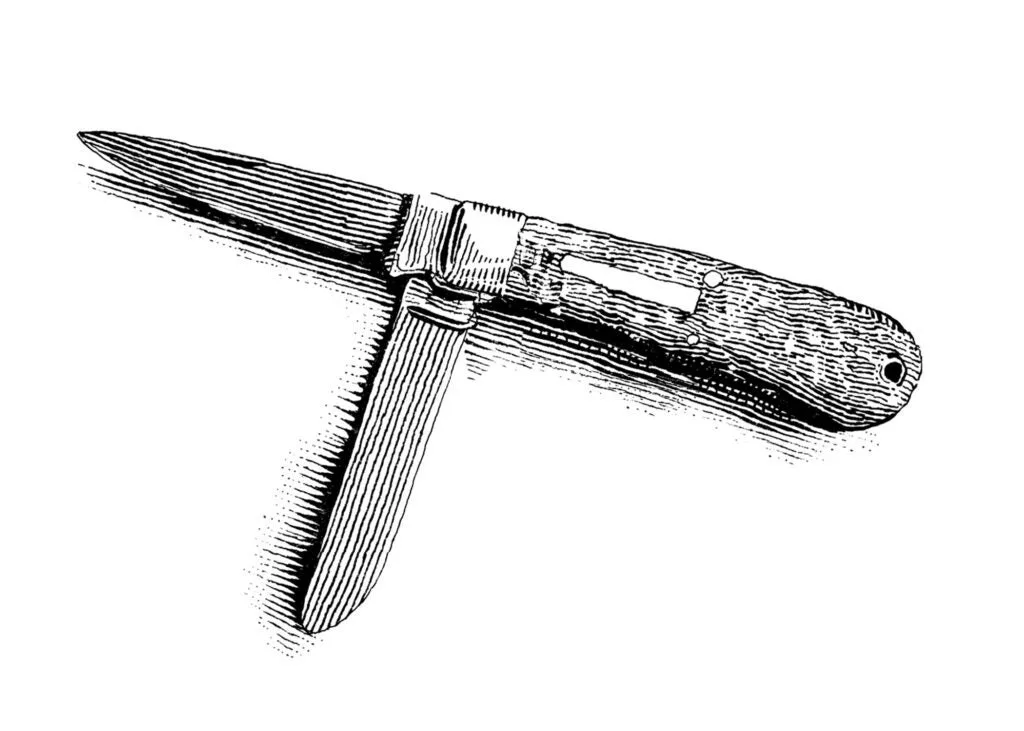

13. Dad’s Knife

Some rare and coveted Remington Bullet Knife models can fetch $2,000 or more. Polly Becker

It wasn’t far, 20 miles of washboard road from my tent to Chase Bridge on the Au Sable River, where I’d cleaned a couple brown trout caught the night before while casting blindly to the solid _blurp_s made by fish sucking down spent-wing mayflies.

I’d cleaned the trout on the same punky log where my father had been cleaning fish since I was a boy, and with the same Remington Bullet Knife. The knife was instantly recognizable by the cartridge case embossed on the handsome stag handle. My dad had traded for it when he was a young man, roughly the same age I was on the night I accidentally left it behind. He’d carried it to Africa and Europe in World War II. I didn’t know then that it was a classic American folding knife, in nearly continuous production from the 1920s to the present day, or that vintage knives such as my father’s Trapper model could command prices in excess of $2,000. Its value to me was entirely sentimental—I wouldn’t have traded that knife for the biggest brown trout in the Au Sable River.

By the time I reached the bridge, 12 hours had passed since I’d forgotten it on the bank, yet there it was, sticking point-down in the log. I still clean a fish with it now and then, because a classic isn’t meant only to sharpen pencils and sleep in a pocket. —Keith McCafferty

14. A Good Ax

This comparatively modern tool harkens back to the days when axes where made by hand and by true craftsmen. Nick Cabrera

Not long ago, some fellows in South Portland, Maine, noticed that if you weren’t lucky enough to be handed down a truly good ax from your father or grand-father, you might be hard-pressed to find one. So they got together to manufacture (by hand) an ultrafine cruiser ax under the name Brant & Cochran

. Based on a model that dates back to the 19th century, their Allagash Cruiser with its Maine wedge pattern is a first-rate camp ax—lighter and smaller than a full-size felling ax and able to do just about anything.

Forged from a chunk of 1050 steel and quenched in the icy salt water of Casco Bay, which is right outside the shop, the B&C Allagash Cruiser has a 21/2-pound head and a 28-inch hickory handle turned by Amish craftsmen. It comes to you wicked sharp, as its makers put it, and it causes big chips to fly. Mine is not old, but it was a classic the day it arrived at my door. I have become very fond of it, and a lot of people would like to be able to say the same, which is why the wait time at present is 18 weeks. Get one and you can hand it down. —D.E.P.

_This story originally ran in the Classics Issue

of_ Field & Stream_. Read more F&S+

stories._