This story first appeared in the January 1954 issue. Over the years, Field & Stream has published many, many stories about Cape buffalo adventures—but none quite like this one.

SOME PEOPLE are afraid of the dark. Other people fear airplanes, ghosts, their wives, death, illness, bosses, snakes or bugs. Each man has some private demon of fear that dwells within him. Sometimes he may spend a life without discovering that he is hagridden by fright—the kind that makes the hands sweat and the stomach writhe in real sickness. This fear numbs the brain and has a definite odor, easily detectable by dog and man alike. The odor of fear is the odor of the charnel house, and it cannot be hidden.

I love the dark. I am fond of airplanes. I have had a ghost for a friend. I am not henpecked by my wife. I was through a war and never fretted about getting killed. I pay small attention to illness, and have never feared an employer. I like snakes, and bugs don’t bother me. But I have a fear, a constant, steady fear that still crowds into my dreams, a fear that makes me sweat and smell bad in my sleep. I am afraid of Mbogo, the big, black Cape buffalo. Mbogo, or Nyati, as he is sometimes called, is the oversized ancestor of the Spanish fighting bull. I have killed Mbogo, and to date he has never got a horn into me, but the fear of him has never lessened with familiarity. He is just so damned big, and ugly, and ornery, and vicious, and surly, and cruel, and crafty. Especially when he’s mad. And when he’s hurt, he’s always mad. And when he’s mad, he wants to kill you. He is not satisfied with less. But such is his fascination that, once you’ve hunted him, you are dissatisfied with other game, up to and including elephants.

The Swahili language, which is the lingua franca of East Africa, is remarkably expressive in its naming of animals. No better word than simba for lion was ever constructed, not even by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Tarzan’s daddy. You cannot beat tembo for elephant, nor can you improve on chui for leopard, mugue for haboon, fisi for hyena or punda for zebra. Farois apt for rhinoceros, too, but none of the easy Swahili nomenclature packs the same descriptive punch as Mbogo for a beast that will weigh over a ton, will take an 88-millimeter shell in his breadbasket and still toddle off, and that combines crafty guile with incredible speed, and vindictive anger with wide-eyed, skilled courage.

From a standpoint of senses, the African buffalo has no weak spot. He sees as well as he smells, and he hears as well as he sees, and he charges with his head up and his eyes unblinking. He is as fast as an express train, and he can haul short and turn himself on a shilling. He has a tongue like a wood rasp and feet as big as knife-edged flat-irons. His skull is armor-plated and his horns are either razor-sharp or splintered into horrid javelins.

The boss of horn that covers his brain can induce hemorrhage by a butt. His horns are ideally adapted for hooking, and one hook can unzip a man from crotch to throat. He delights to dance upon the prone carcass of a victim, and the man who provides the platform is generally collected with a trowel, for the buffalo’s death-dance leaves little but shreds and bloody tatters.

I expect I have looked at several thousand buffalo at close range. I have stalked several hundred. I have been mixed up in a stampede in high reeds. I have stalked into the precise middle of a herd of two hundred or more, and stayed there quietly while the herd milled and fed around me. I have crawled after them, and dashed into their midst with a whoop and a holler, and looked at them from trees, and followed wounded bulls into the bush, and have killed a couple. But the terror never quit. The sweat never dried. The stench of abject fear never left me. And the fascination for him never left me. Toward the end of my first safari I was crawling more miles after Mbogo than I was walking after anything else—still scared stiff, but unable to quit. Most of the time I felt like a cowardly bullfighter with a hangover, but Mbogo beckoned me on like the sirens that seduced ships to founder on the rocks.

FOR THIS I blame my friend Harry Selby, a young professional buffalo—I mean hunter—who will never marry unless he can talk a comely cow mbogo into sharing his life. Selby is wedded to buffalo, and when he cheats he cheats only with elephants. Four times, at last count, his true loves have come within a whisker of killing him, but he keeps up the courtship. It has been said of Selby that he is uninterested in anything that can’t kill him right back. What is worse, he has succeeded in infecting most of his innocent charges with the same madness

Selby claims that the buffalo is only a big, innocent kind of he-cow, with all the attributes of bossy, and has repeatedly demonstrated how a madman can stalk into the midst of a browsing herd and commune with several hundred black tank cars equipped with radar and heavy artillery on their heads without coming to harm. His chief delight is the stalk that leads him into this idyllic communion. If there are not at least three mountains, one river, a trackless swamp and a cane-field between him and the quarry, he is sad for days. Harry does not believe that buffalo should be cheaply achieved.

Actually, if you just want to go out and shoot a buffalo, regardless of horn size, it is easy enough to get just any shot at close range. The only difficulty is in shooting straight enough, and/or often enough, to kill the animal swiftly, before it gets its second wind and runs off into the bush, there to become an almost impregnable killer. In Kenya and Tanganyika, in buffalo country, you may almost certainly run onto a sizable herd on any given day. I suppose by working at it I might have slain a couple of hundred in six weeks, game laws and inclination being equal.

As it was, I shot two—the second better than the first, and only for that reason. Before the first, and in between the first and the second, we must have crawled up to several hundred for close-hand inspection. The answer is that a 42- or 43-inch bull today, while no candidate for Rowland Ward’s records, is still a mighty scarce critter, and anything over 45 inches is one hell of a good bull. A fellow I know stalked some sixty lone bulls and herd bulls in the Masai country recently, and never topped his 43-incher.

I looked at Mbogo and Mbogo looked at me. He was 50 to 60 yards off, his head low, his eyes staring right down to my soul. He looked as if I had murdered his mother.

But whether or not you shoot, the thrill of the stalk never lessens. With your glasses you will spot the long, low black shape of Mbogo on a hillside or working out of a forest into a swamp. At long distances he looks exactly like a great black worm on the hill. He grazes slowly, head down, and your job is simply to come up on him, spot the good bull, if there is one in the herd, and then get close enough to shoot him dead. Anything over thirty yards is not a good safe range, because a heavy double—a .450 No. 2 or a .470—is not too accurate at more than one hundred yards. Stalking the herd is easier than stalking the old and wary lone bull, which has been expelled from the flock by the young bloods, or stalking an old bull with an askaria young bull that serves as stooge and bodyguard to the oldster. The young punk is usually well alerted while his hero feeds, and you cannot close the range satisfactorily without spooking the watchman.

It is nearly impossible to describe the tension of a buffalo stalk. For one thing, you are nearly always out of breath. For another, you never know whether you will be shooting until you are literally in the middle of the herd or within a hundred yards or so of the single-o’s or the small band. Buffalo have an annoying habit of always feeding with their heads behind another buffalo’s rump, or of lying down in the mud and hiding their horns, or of straying off into eight-foot sword-grass or cane in which all you can see are the egrets that roost on their backs. A proper buffalo stalk is incomplete unless you wriggle on your belly through thorn-bushes, shoving your gun ahead of you, or stagger crazily through marsh in water up to your rear end, sloshing and slipping and falling full length into the muck. Or scrambling up the sides of mountains, or squeezing through forests so thick that you part the trees ahead with your gun barrel.

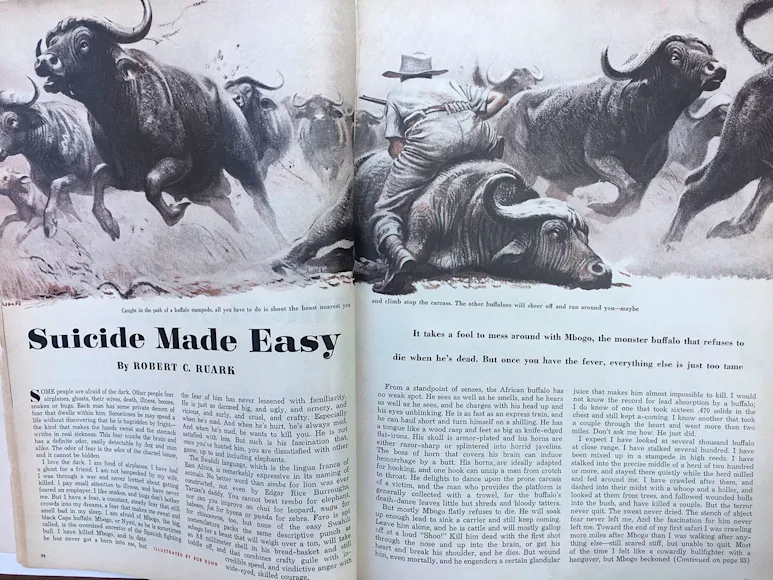

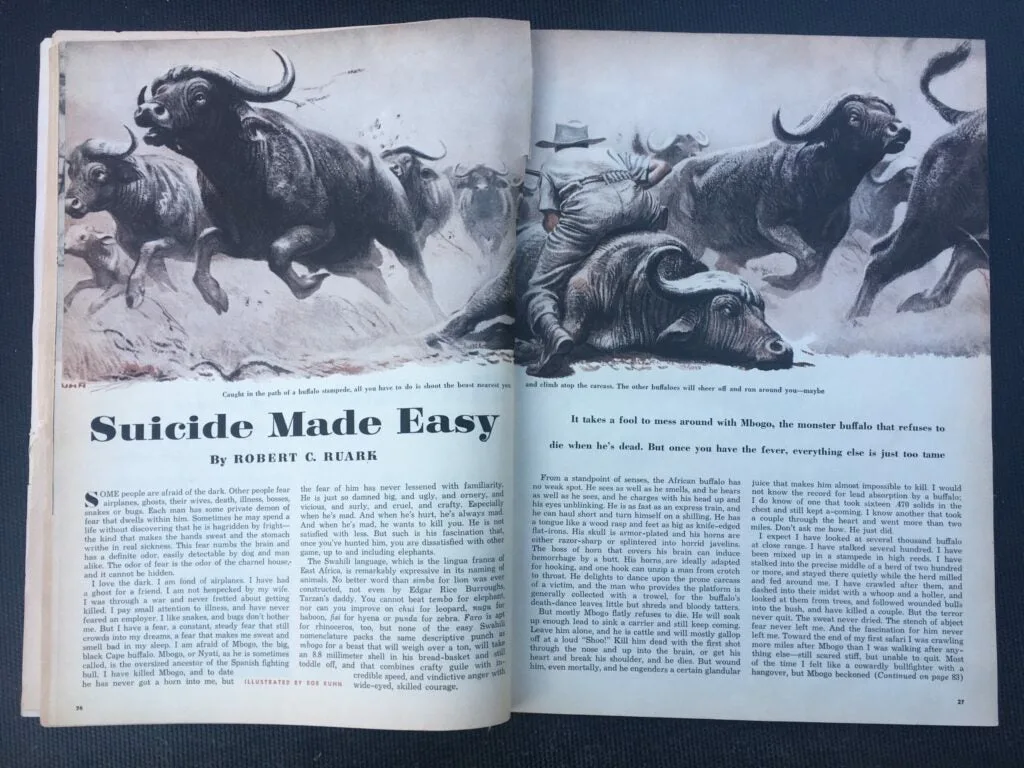

The caption with the original illustration, by Bob Kuhn, read: “Caught in the path of a buffalo stampede, all you have to do is shoot the beast nearest you and climb atop the carcass, then the other buffalo will sheer off and run around you—maybe.” Field & Stream

THERE IS no danger to the stalk itself. Not really. Of course, an old cow with a new calf may charge you and kill you. Or the buffs that can’t see you or smell you, if you come upwind in high cover or thick bush, might accidentally stampede and mash you into the muck, only because they don’t know you’re there. Two or three hundred animals averaging 1,800 pounds apiece make a tidy stampede when they are running rump to rump and withers to withers. I was in one stampede that stopped short only because the grass thinned out, and in another that thoughtfully swerved a few feet and passed close aboard us. If the stampede doesn’t swerve and doesn’t stop, there is always an out. I asked Mr. Selby what the out was.

“Well,” he replied, “the best thing to do is to shoot the nearest buffalo to you, and hope you kill it dead so that you can scramble up on top of it. The shots may split the stampede, and once they see you perched atop the dead buffalo they will sheer off and run around you.”

I must confess I was thoroughly spooked on buffalo before I ever got to shoot one. I had heard a sufficiency of tall tales about the durability and viciousness of the beasts—tall tales, but all quite true. I had been indoctrinated in the buffalo hunter’s fatalistic creed: Once you’ve wounded him, you must go after him. Once you’re in the bush with him, he will wait and charge you. Once he’s made his move, you cannot run, or hide, or climb a tree fast enough to get away from a red-eyed, rampaging monster with death in his heart and on his mind. You must stand and shoot it out with Mbogo, and unless you get him through the nose and into the brain, or in the eye and into the brain, or break his neck and smash his shoulder and rupture his heart as he comes, Mbogo will get you. Most charging buffalos are shot at a range of from fifteen to three feet, and generally through the eye.

ALSO, we had stalked up to a lot of mbogo before I ever found one good enough to shoot. We had broken in by stalking a herd that was feeding back into the forest in a marsh. Another herd, which had already fed into the bush and which we had not seen, had busted loose with an awful series of snorts and grunts and had passed within a few feet, making noises like a runaway regiment of heavy tanks. This spooked the herd we had in mind, and they took off in another direction, almost running us down. A mud-scabby buffalo at a few feet is a horrifying thing to see, I can assure you,

The next buff we stalked were a couple of old and wary loners, and we were practically riding them before we were able to discern that their horns were worn down and splintered from age and use and were worthless as trophies. This was the first time I stood up at a range of twenty-five yards and said “Shoo!” in a quivery voice. I didn’t like the way either old boy looked at me before they shooed.

The next we stalked showed nothing worth shooting, and the next we stalked turned out to be two half-grown rhino in high grass. I was getting to the point where I hated to hear one of the gun-bearers say, “Mbogo, Bwana,” and point a knobby, lean finger at some flat black beetles on a mountainside nine miles away. I knew that Selby would say, “We’d best go and take a look-see,” which meant three solid hours of fearful ducking behind bushes, crawling, cursing, sweating, stumbling, falling, getting up and staggering on to something I didn’t want to play with in the first place. Or in the second place, or any place.

But one day we got a clear look at a couple of bulls—one big, heavily homed, prime old stud and a smaller askari, feeding on the lip of a thick thorn forest. They were feeding in the clear for a change, and they were nicely surrounded by high cane and a few scrub trees, which meant that we could make a fair crouching stalk by walking like question marks and dodging behind the odd bush. The going was miserable underfoot, with our legs sinking to the knees in ooze and our feet catching and tripping on the intertwined grasses, but the buff were only a few thousand yards away and the wind was right; so we kept plugging ahead.

“Let’s go and collect him,” said Mr. Selby, the mad gleam of the fanatic buff hunter coming into his mild brown eyes. “He looks like a nice one.”

Off we zigged and zagged and blundered. My breath, from overexertion and sheer fright, was a sharp pain in my chest, and I was wheezing like an overextended pipe-organ when we finally reached the rim of the high grass. We ducked low and snaked over behind the last bush between us and Mbogo. I panted. My belly was tied in small, tight knots, and a family of rats seemed to inhabit my clothes. I couldn’t see either buffalo, but I heard a gusty snort and a rustle.

Selby turned his head and whispered: “We’re too far, bur the askari is suspicious. He’s trying to lead the old boy away. You’d best get up and wallop him, because we aren’t going to get any closer. Take him in the chest.”

I lurched up and looked at Mbogo, and Mbogo looked at me. He was 50 to 60 yards off, his head low, his eyes staring right down my soul. He looked at me as if he hated my guts. He looked as if I had despoiled his fiancé, murdered his mother, and burned down his house. He looked at me as if I owed him money. I never saw such malevolence in the eyes of any animal or human being, before or since. So I shot him.

I was using a big double, a Westley-Richards. 470. The gun went off. The buffalo went down. So did I. I had managed to loose off both barrels of this elephant gun, and the resulting concussion was roughly comparable to shooting a three-inch anti-aircraft gun off your shoulder. I was knocked as silly as a man can be knocked and still be semiconscious. I got up and stood there stupidly, with an empty gun in my hands, shaking my head. Somewhere away in Uganda I heard a gun go off and Mr. Selby’s clear tone came faintly.

“I do hope you don’t mind,” said he. “You knocked him over, but he got up again and took off for the bush. I thought I’d best break his back, although I’m certain you got his heart. It’s just that it’s dreadfully thick in there, and we’d no way of examining the wound to see whether you’d killed him. He’s down, over there at the edge of the wood.”

MBOGO WAS DOWN, all right, his ugly head stretched out. He was lying sideways, a huge, mountainous hulk of muddy, tick-crawling, scabby-hided monster. There was a small hole just abaft his forequarters, about three inches from the top of his back-Mr. Selby’s spine shot.

“You got him through the heart, all right,” said Mr. Selby cheerfully. “Spine shot don’t kill ’em. Load that cannon and pop him behind the boss in the back of his head. Knew a dead buffalo once that got up and killed the hunter.”

I sighted on his neck and fired, and the great head dropped into the mud. I looked at him and shuddered. If anything, he looked meaner and bigger and tougher dead than alive.

“Not too bad a buff, “Selby said. “Go forty-three, forty-four, Not apt to see a bigger one unless we’re very lucky. Buff been picked over too much. See now ’twasn’t any use my shooting him. He’d have been dead twenty yards inside the bush, but we didn’t know that, did we? Kidogo! Adam! Taka head-skin!” he shouted to the gun-bearers and sat down on the buffalo to light a cigarette. I was still shaking.

As I said, I was shooting a double-barreled Express rifle that fires a bullet as big as a banana. It is a 500-grain bullet powered by 75 grains of cordite. It has a striking force of 5,000 foot-pounds of energy. It had taken Mbogo in the chest. Its impact knocked him flat—2,500 pounds of muscle. Yet Mbogo had not known he was dead. He had gotten up and had romped off as blithely as if I had fired an air-gun at his hawser-network of muscles, at his inch-thick hide that the natives use to make shields. What had stopped him was not the fatal shot at all, but Harry’s backbreaker.

“Fantastic beast,” Selby murmured. “Stone-dead and didn’t know it.”

We stalked innumerable buffalo after that. I did not really snap out of the buffalo-fog until we got back in Nairobi, to find that a friend, a professional hunter, had been badly gored twice and almost killed by a “dead” buffalo that soaked up a dosen slugs and then got up to catch another handful and still boil on to make a messy hash out of poor old Tony.

I am going back to Africa soon. I do not intend to shoot much. Certainly I will never kill another lion, nor do I intend to duplicate most of the trophies I acquired on the last one. But I will hunt Mbogo. In fear and trembling I will hunt Mbogo every time I see him, and I won’t shoot him unless he is a mile bigger than the ones I’ve got. I will hate myself while I crawl and shake and tremble and sweat, but I will hunt him. Once you’ve got the buffalo fever, the rest of the stuff seems mighty small and awful tame. This is why the wife of my bosom considers her spouse to be a complete and utter damned fool, and she may very well be right.

_You can find the complete F&S Classics series here

._ Or _read more F&S+

stories._