Famous for their displays during the spring breeding season, sage grouse inhabit the steppes of the American west. Big birds, they can weigh up to 6 pounds, and they can look even bigger when they puff their air sacs full during their spring mating dance. The sage grouse served not only as a source of food to Native Americans, but the bird’s lekking behavior inspired both ceremonial costumes and dances. The sage grouse is a genuine icon of the West—and currently a bird in serious population decline

.

A favorite of wildlife photographers and birders, the sage grouse is considered a trophy gamebird among wingshooters, although as sage grouse habitat shrinks and populations decline, there are only a few, tightly controlled opportunities to hunt them. Given their significance as a symbol of the West, sage grouse matter. Whether you are a hunter, a birder, someone who cares about wild places, or some of all three, it’s important to understand the sage grouse, its habits, and the threats to its population.

Appearance, Range, and Habitat

Stan / Adobe Stock, USDA, Field & Stream

The sage grouse is the largest of North America’s many grouse species. Adult males, sometimes nicknamed “bombers” for their sheer size, can top 6 pounds. The bird’s feathers are a mottled gray-brown, to blend with their sage habitat, and they have black bellies. The males wear a black collar above a white breast, and long, pointed tailfeathers.

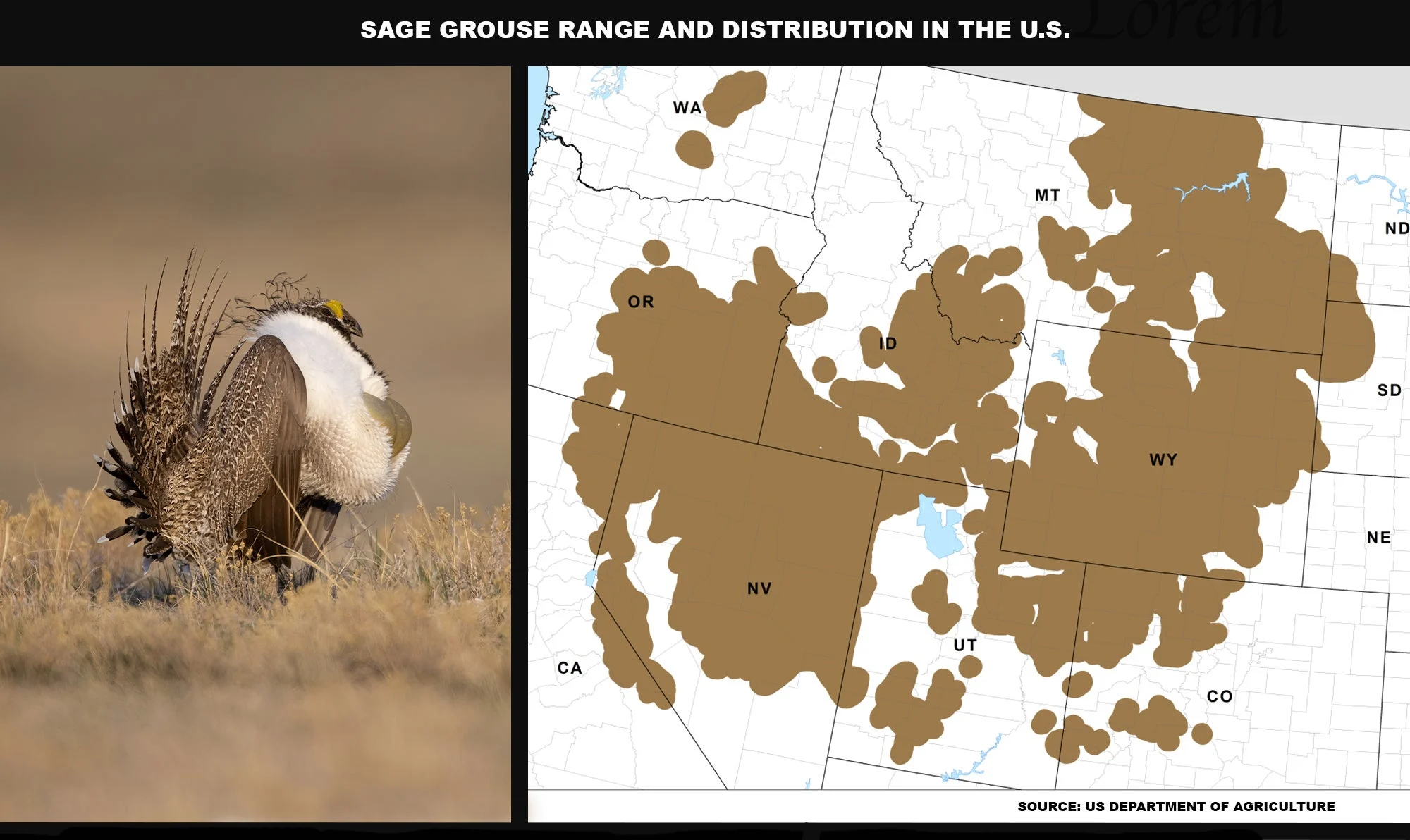

When the males display in the spring, they inflate two air sacs on their chests and spread their tails into a spiky fan, which is the most familiar image of the sage grouse in most people’s minds. As mentioned, sage grouse inhabit the sage brush steppes of the West, a region including parts of Montana, Wyoming, Utah, Nevada, California, Oregon, Idaho, and bits of surrounding states. The birds live in sagebrush, nesting in heavier growth, displaying in open areas and feeding on the plant’s leaves, buds, and flowers. While sage brush leaves make up the bulk of the sage grouse’s diet, the birds also feed on other plants and some insects. Sage grouse lack a muscular gizzard capable of grinding seeds, so their only use of agricultural fields is to feed on alfalfa. Sage grouse derive enough nutrition from sage leaves that they actually gain weight during the coldest months and arrive at breeding season in good condition for the rigors of the lekking season.

Sage Grouse: Breeding Behaviors

A greater sage grouse hen walks by a strutting male on a lek in springtime. Elizabeth-BoehmDanita-Delimont / Adobe Stock

Sage grouse are best known for their breeding behavior on leks, which can be any area of short grass with high visibility, such as a grass-stubble flat, a dry lakebed, or a recent burn. Grouse gather on the lek, where the hens watch males display. The male grouse establish and defend territories on the lek, which may only be a few yards across. The males fan their tails and pump their air sacs up and down. Holding their wings tightly against their sides, the males make a swishing sound as the stiff breast feathers rub against the wings and the sac heaves up and down. Females choose males based on their displays. Only a few males do all the breeding, and they have no involvement in nesting or raising the young after mating. Males will strut, head down and beak to beak, defending their territories, and they often fight with their wings if they are unable to drive their rival away with intimidation.

Females scratch a nest into the soil underneath a sage brush or in grass. They line the nest with grass, twigs, and their own down, then lay clutches of anywhere from four to 11 eggs. Young sage grouse cannot digest sage until the age of three weeks or so. They subsist on insects at first until they are able to feed on sage.

Sage Grouse Conservation

With populations estimated at 16 million before settlement, sage grouse numbers have plummeted to an estimated 200,000 birds. The simple reason for their decline is that sage grouse need space. Lots of it. A band of grouse may require up to 75,000 acres of sage around a lek. They need to move around to use different types of habitats within the sage steppes, and any type of disturbance has an impact on populations. Numbers have been declining steadily, with populations dropping an alarming 80 percent between 1966 and today. The birds are very sensitive to habitat fragmentation, and the opening of lands to energy extraction presents a serious threat. Low flyers, sage grouse can injure or kill themselves on livestock fences, and in some areas warning markers attached to the top strands of fencing do seem to help. That problem is small, though, compared to the larger issues of balancing development, especially energy development, with a bird that evolved to have wide open spaces to itself.

Sage Grouse Hunting

Although sage grouse numbers have fallen and continue to decline, some local populations are healthy enough to allow limited hunting opportunities. Given the huge territory they inhabit, the first step is finding birds. It’s sometimes possible to spot birds flying to feed in the morning and evening, giving you a starting place for the hunt. If you can, seek out locals and ask where they see birds. After that, you’ll need to cover ground. Dogs are a huge help, greatly increasing the amount of ground you can cover. Be sure to pack plenty of water for yourself and the dogs, however, as sage grouse country is dry and often hot.

A male sage grouse flushes over a sage flat. David / Adobe Stock

Sage grouse cover can be quite sparse, and even pointed birds may flush at a distance in front of the dog. A good shotgun for sage grouse hunting

should be light enough to carry for miles, but it also should be enough gun for a bird that can weigh 6 pounds. A 12-gauge loaded with size 5 or 6 shot makes a good choice. Remember, too, that sage grouse are often found together and may flush in a staggered manner. Shoot twice and miss with an O/U, and you may find yourself standing among flushing birds with your gun broken open to reload. A pump or semiauto makes sense in such a situation, as you have an extra shell and it’s faster to reload. That’s something you have to think about, given how far you may have to walk to find these birds in the first place.

Because they eat sage, these grouse have bad rap as table fare. And they can indeed have a strong flavor. (The sage they eat, by the way, is not the same sage we eat.) Also, like other prairie grouse, sage grouse have dark breast meat and light leg meat. One sensible approach is to cook the breast and legs separately. Saute the legs in butter and garlic. Cook the breast rare, in a skillet or on the grill, slice it thin, and enjoy it as a taste of one of North America’s wildest gamebirds.