Since the first of July, I’ve been running 10 trail cameras across five different properties, all in the same county in Southwest Kentucky. Two of those cameras are on my own 72-acre farm on the south end of the county, and the rest are scattered on small farms (40 to 100 acres each) on the north end of the county.

I’m scouting for deer, of course, but also keeping a close eye on the turkey hatch. Right now, as in many states, Kentucky is logging poult sightings from the public as part of their annual summer brood survey. These voluntary surveys are the only way for many states to get a handle on the year’s big-picture turkey hatch and poult-recruitment numbers. That information is critical for setting spring turkey hunting regulations.

It’s no secret that Eastern wild turkey numbers, particularly in the Southeast, have been declining in recent years, and some states are making pretty aggressive regulation changes—many of them at the urging of hunters—in an attempt to turn the tide. If seeing and hearing fewer turkeys in the spring bothers you, you need to be watching for poults right now, and participating in brood surveys if your state offers them.

Good Turkey Hatch Vs. Bad Hatch, Only Miles Apart

The poults in this photo (lower left corner) are only about the size of grouse, indicating a late brood. Will Brantley

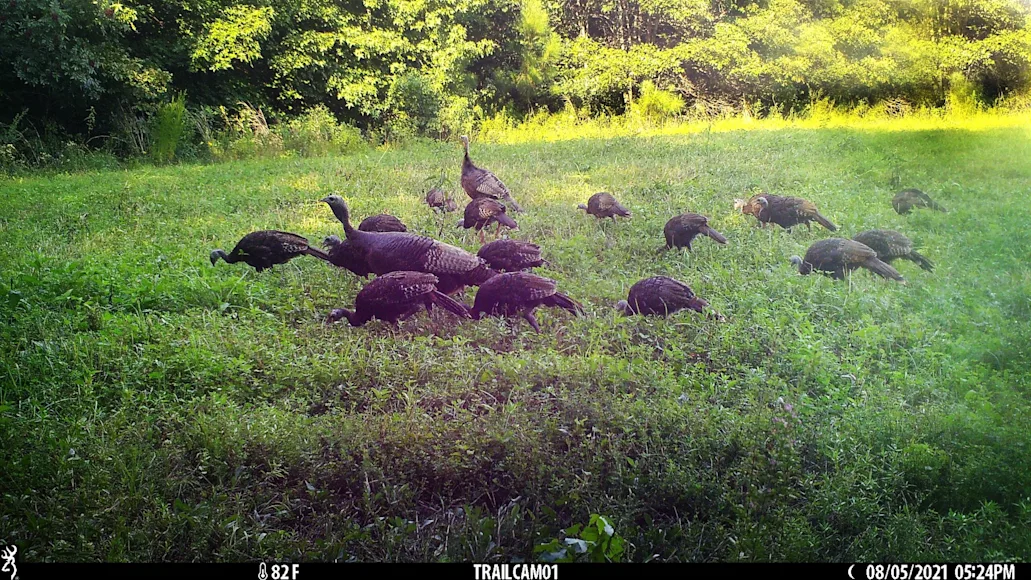

On our farm, dozens of trail-camera photos and a couple of in-person sightings have confirmed at least three adult hens with a total of 28 poults between them. That’s solid. Two of those hens are running together, and their combined poults look to be about three-quarters grown; other than being a bit smaller, they’re almost indistinguishable from the mother hens. That’s what poults should look like in early August around here. The other hen has 8 little turkeys in tow, all the size of rooster pheasants, meaning she hatched her brood a little later.

My neighbor Bill, who co-owns and helps manage a larger property bordering ours, says this year’s local turkey hatch is the best he’s seen in years. “We’re running three cell cameras, and between them and just being out driving around, we’re seeing hens and poults everywhere,” he told me.

But the difference between our area and elsewhere couldn’t be starker. On the other four farms I’m scouting farther north, I’ve seen a total of two broodless hens and one hen with four poults. And as you can see in the August 4 trail-cam photo above, those four poults were each about the size of a grouse, meaning they were about 6 weeks old. With a 26- to 28-day nest incubation period, poults of that size suggest that the hen nested in early June—more than a month after our turkey season ended. It’s likely that the hen had a few nest failures before finally hatching that late brood.

On the one hand, four poults are better than no poults. On the other hand, two cameras in a much smaller contiguous area captured 86 percent more baby turkeys than eight cameras watching hundreds of non-contiguous acres.

This county is not large—we’re talking two areas 15 miles apart—and so there’s not a lot of habitat variation. And that rules the weather out of the equation, too, since rainy springs are often blamed for poor turkey hatches.

Predator Control Appears To Make All the Difference

The author and his son, Anse, with a coyote they trapped. Last year, the author trapped six coyotes on his 72-acre farm. Will Brantley

I plant food plots and conduct selective prescribed fires every February and March to maintain early successional habitat. We burn 15 to 20 acres each winter in rotational sections across the property. That creates good nesting and brooding habitat, but it’s a drop in the bucket considering the entire landscape. The farms in the north end of the county have thickets, too, along with nearby cattle operations, plenty of row crops, and mature roosting trees. And the turkey hunting pressure seems heavier down near my farm than on the other end of the county.

So what’s the difference? The biggest that I can see is that there’s a lot more predator trapping on my end of the county. Last year on my place I caught six coyotes, two grey foxes, three raccoons, and four opossums. That’s 15 sets of teeth gone from 72 acres. I don’t know Bill’s catch numbers, but I know he’s targeted the nest predators—raccoons, opossums, skunks—intensively on his place as well.

Last summer and fall, before trapping season, my trail cameras were capturing coyote photos virtually every night. This year, I’ve gotten one coyote picture since February, when trapping season ended. Bill called to tell me that his coyote photos have trailed off significantly as well—though he has gotten repeated pictures of a pair of dogs that do seem to have a taste for turkeys (that’s one of them chasing a hen in the image below).

A trail-cam photo of a coyote chasing a hen turkey on a farm bordering the author’s. Bill Sanders

Trapping has its detractors, and I’m sure some of them will speak up about this. Some conservation groups downplay trapping as being too costly and time-consuming to be a viable, large-scale management strategy. Better to focus on habitat improvements, they say. And even some within the pro-hunting community point to studies suggesting that trapping coyotes doesn’t really do much to lessen their impacts on turkey poults and deer fawns, since some coyotes are residents and some are transients, and the transients quickly fill in the voids when resident coyotes are caught.

I personally don’t waste my time worrying about what people say to downplay the importance of predator control. Of course trapping is hard work, but so is other habitat improvement, and I’d much rather run a trapline than sit on a tractor. Maybe large-scale predator control isn’t realistic, but that doesn’t mean running a trapline on your place won’t help your turkey numbers.

As for the resident/transient coyote argument, I’m sure that study was valid and conducted by people with more degrees than I have. I just personally haven’t seen the same result here. I killed those six coyotes last winter, haven’t seen many others since, and all the sudden we have baby turkeys running around everywhere.

Maybe it’s a coincidence. Or maybe those poults are there directly as a result of predator trapping. Or it’s some byproduct of the two. Whatever it is, after a few tough turkey seasons, I like knowing those poults are out there.