BEFORE I GO panfishing in the late summer, I like to listen to a little music. Field crickets, katydids, and grasshoppers are among the insect world’s most accomplished noisemakers. Their very best performances, however, are given on the end of a hook. Pond and creek bass, bluegills, crappie, and bullheads may not appreciate their chirps and whirrs, but they call for encores when you offer them as bait.

Many a country cane poler once spent the days of Indian summer dapping these morsels under overhanging trees along creekbanks, flicking them into the center holes of lily-pad clusters, or dropping them back into the shady water under rural road bridges. Many fishermen have forgotten how deadly these abundant baits can be on small, quiet waters. If your fishing normally takes you on big waters for big fish, wipe the gas off your hands and enjoy the relaxed pleasure of this panfishing tactic for August, September, and October.

Deep South bream specialists know and love the cricket year-round. The rest of us wait until the first flicker of coral spreads from one bush maple to another, and the cut-over hayfields turn a subtle yellow. Then all the noisemakers become urgently active. The common red-legged grasshopper whirrs up from the ground, where it lays its eggs, to light upon weed stalks. Katydids loudly fill the night with the sound of their own name. On a September afternoon, when the sun feels good on a northern slope, the crickets’ song hints at impending frosts.

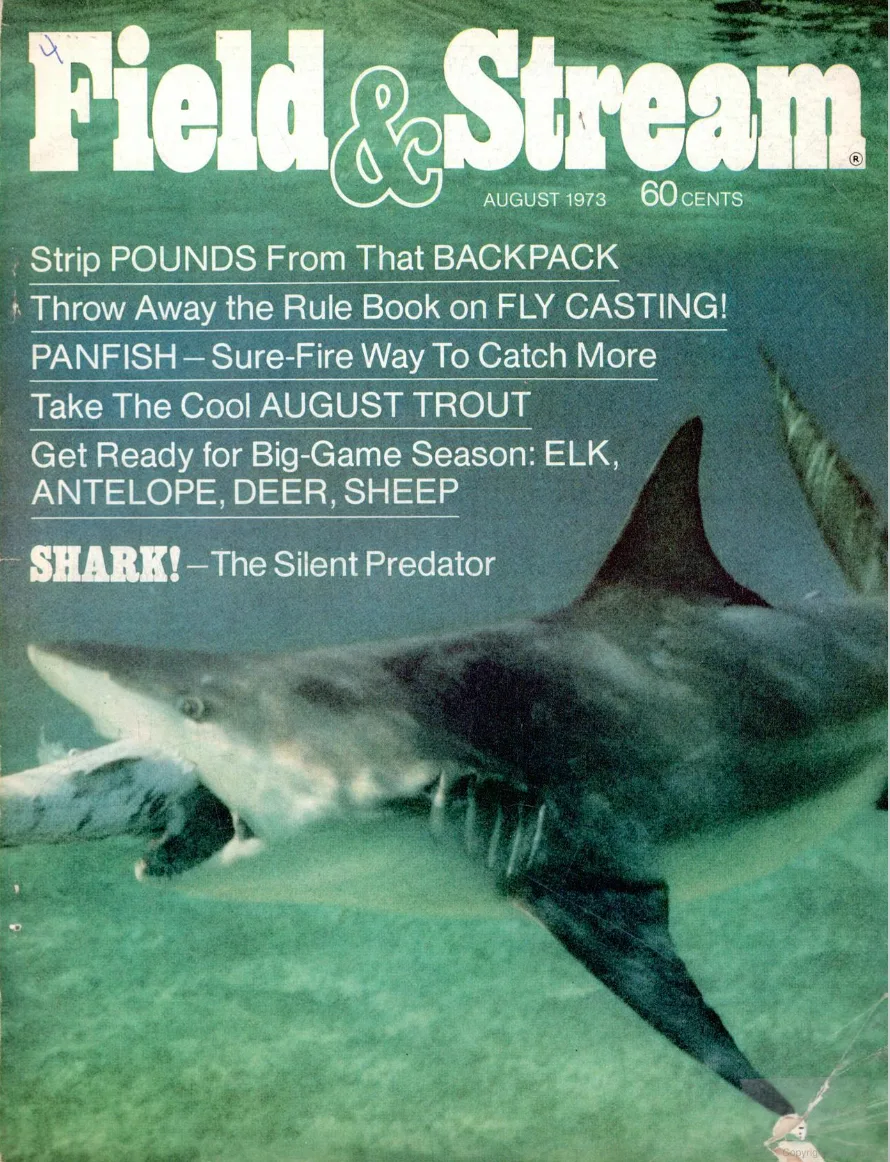

The August 1973 cover featured the “silent predator”—SHARK! Field & Stream

Slab-sided bluegills and crappies relish the big, fat, black field crickets. These are the chirpers whose repetitive notes can be calculated to tell you the air temperature. They are where you hear them—all over. After a bit of practice, you begin to spot them peeping from a tuft of weeds, hopping down grassy boulevards, meditating under boards, rocks, and thrown-out pieces of flat junk.

Don’t bother trying to catch them in hayfields, where they are abundant. A hayfield cricket is always three straws ahead of your fingers. The cricket that entrusts his security to a field rock is your best bet. Rocks that have sunk partway into the ground are inviting caverns for this fat fiddler. They are good collecting spots at any time of day, but particularly so as the evening cool descends, since crickets like their retained warmth.

When you lift their rock, the crickets scatter. The novice cricket-catcher has the same problem as the beginning bird hunter: out of the abundance of moving forms, he can’t make up his mind which to try for, and so winds up with none. Luckily, crickets are stupid. Although they can reputedly leap 100 times their own length, it never seems to occur to them to try it straight up. Their habit of running into blind corners will yield you about three dozen crickets per hour of rock turning.

A seeding of rocks around your lawn will give you a source of these portly musicians from about June, when the nymphs mature as adults, until a couple of hard frosts have knocked the majority off.

Crickets can be bred and raised as a year-round bait; plans for cricket factories are readily obtainable. Since they are not as effective a bait in cold water (below about 45 degrees) as mice or other tidbit-type baits, I haven’t found the advantage worth the bother.

A nylon stocking or heavy plastic bag punctured with tiny air holes, and secured with a rubber band, makes an excellent one-day container for either hoppers or crickets. If you plan to keep these baits a few days, buy a regular cricket box. These plastic containers aren’t as fancy as the jade or ivory cages the Chinese once kept pet crickets in, but they are gnaw-proof and easily cleaned. A few juicy lettuce leaves give the baits both food and moisture.

Have you ever seen a fisherman, preferably in full wader dress, trying to catch grasshoppers in the middle of the day? A warm grasshopper is guaranteed to take off just as your hand descends. It will land in a patch of poison ivy, ground briar, or sharp-tipped weed stalks. Ergo, it is best to collect grasshoppers in the early morning or late evening, when their reflexes are chilled off. What everyone doesn’t know is that a surprising number of cold hoppers are bright enough to drop into ground duff, where they are exceedingly hard to spot. It always takes a longer amount of the prime fishing hours to collect a worthwhile number of grasshoppers than you think it will.

How to Catch Crickets for Bait

The best grasshopper grabber I’ve employed is a worn-out bedspread with fuzzy synthetic innards. This I lay on the leeward side of a patch of weeds. Circling around, I drive the game toward it; any that light on those nylon fibers get hung up good. The higher the sun, the better, since there are just that many more grasshoppers ready to fly, and the fishing’s slow then, anyway.

Grasshoppers that show a yellow “fan” when they fly have a tough skin. They aren’t as appealing to bluegill and crappie as crickets or the soft green and yellow hoppers, but they are abundant. Bullheads are fond of several of them mashed on a hook, and fished a few inches off bottom.

The novice cricket-catcher has the same problem as the beginning bird hunter: out of the abundance of moving forms, he can’t make up his mind which to try for, and so winds up with none. Luckily, crickets are stupid.

The hump-winged katydids are easy to catch, but yet they seem to be the least abundant of these latesummer baits. Large, succulent, and bright green, they are relished by all pan-size bass, and are murder on creek smallmouth. Look for them on the lower branches of trees and large shrubs, and around porch lights at night. If you approach slowly, you can grab them by hand. Try them in a stream pool shaded by a leaning tree and see what happens.

There is a grasshopper, which hangs around damp meadows and watercourse edges, that is to a common hopper as the 747 is to a DC-3. They are nearly 3 inches long, with a shiny, meaty look. Smart small-river fishermen in the West and Southwest use them for channel catfish. They are even better than plastic worms for pond bass in late August and September.

An Irresistible Cricket Rig

Unicorn Pond is 43 acres of state-owned water on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. I like to visit it and other Shore ponds as a change from Baltimore reservoir fishing, because it hasn’t much of a reputation for bass. I can therefore spend a weekday fishing in solitary peace from a car-top boat or inflatable.

One bright, hot September day, I found Unicorn full of floating mats of green goo. Most of the morning I spent fishing the deep (to 6 feet) water by the ramp, because it was free of goo. I don’t know how many bluegills I caught on a tiny spinner baited with a cricket, fished on 2-pound-test line 5 feet below a dime-size bobber, but I kept 24. They were nice, chunky bluegills, at least 1/2-pound each.

The spinner was just heavy enough to pull the cricket under, and sink it kicking all the way. The bluegills did not always hit immediately—and when they won’t hit a cricket pronto, they are really off their feed—but the flash and meat combo always proved irresistible in a minute or two.

These spinners I make myself, using a light wire shaft, a No. 00 Colorado blade, a single tiny red or fluorescent green bead, and a No. 10 hook. Besides their value to the ultralight spinner when bluegills are down deep, a spinner and cricket will take big pond crappie which refuse to hit minnows.

The tiny bobber has several uses. It provides a scrap of casting weight, and it keeps crickets or hoppers at the desired depth. It can be used for a sneakier purpose, too. Use it with a cricket or hopper on a plain, finewire No. 12 or No. 10 hook. Cast this rig to tree-shaded, deeper water along pond shorelines. Bluegills will come up for a vicious strike at the bait as it struggles near the bobber. Perhaps they take the bobber for a bit of flotsam—and escape.

I think you will find fine-wire, Aberdeen pattern hooks most useful all around. There are pin-type hooks made for grasshopper fishing, but they kill the bait too quickly. Those I’ve tried have been too heavy for realistic surface presentation. All the late-summer singers have nice collars for your hooking convenience. When the bait is used with a spinner, I hook it through the eyes.

Take plenty of hooks. Sunfish and bullheads swallow these baits, longshank hook and all, clear down to their belly buttons. If you try to extract a fine wire hook, it bends like a pretzel. I just sigh, cut the line, tie on another, and try to remember to retrieve the hook later when I clean the catch.

Why bother with the real, live thing, you say, when there are neat, clean, artificial imitations available by the dozen? Sure, if you insist, though that gets us away from the simple, earthy angling life. One company offers a lively plastic cricket in its line, and there are many good, sinking rubber “spiders” which roughly suggest terrestrial insects. Big Muddler Minnows, of course, duplicate the big hoppers bass like. My own favorite fakes are beetle and grasshopper deer hair bugs, made with black hair for the former and light brown or yellow-brown hair for the latter.

I still prefer the inconvenient but live creature. In the low, often crystal-clear water of late August through October, nothing matches its action for wary fish. All too often bluegills can bite an artificial faster than I can strike. Besides, I like to hear the baits chirping and popping in their container in the still air of a lazy afternoon.

The Right Rod

Though I find myself choosing an ultralight spinning outfit (7-foot rod for pond fishing; 5-foot rod for creek work; both rods with soft, even action) most times for cricket and hopper fishing, a fly rod is needed for certain situations. You can control a sinking bait better in still water with it, when no lead or spinner is wanted. As fall progresses, panfish move into sun-warmed shallows right against shore. With a fly rod, you can work these areas with minimum water disturbance.

My 7-foot ultralight spinning rod has a collet handle and will convert to a fly rod handling DT4F line. That’s just right for panfish-size hair bugs or small live crickets and hoppers. A bass bug rod is best for the big katydids, grasshoppers and Muddler Minnows. If you have a naturally sloppy fly casting motion, you won’t pop off the live baits.

By midafternoon of that day on Unicorn Pond, I was in the upper, shallow end, gazing at the drifting mats of goo. Splashes and bulges followed the mats. In my bait cage were some two dozen of the jumbo marsh hoppers. I shortly found that if I could put one of these baits in any little hole in a mat, gently pull it under, and let it sink, I got a bass. None of them exceeded 13 inches; on the other hand, I caught and released twenty in two hours time. On 2-pound test line, that’s fun.

In another type of pond, bluegills, bass, and crappie may hide out under lily pads. It is very difficult to use a fly rod or spinning rod to work those inviting openings that dot lily-pad clusters. The line invariably fouls up on leaf edges and drags the hook into a stem.

That’s the time to try one of the oldest—and often the best-panfishing weapons: the cane pole. I’m no Amazon, but I find a 16-foot, telescoping, hollow fiberglass pole easy and pleasant to use. A number of firms offer fiberglass poles for special purposes, such as bream fishing, bass jigging, and so forth, in lengths to 20 feet.

With a cane pole and an electric-motor-equipped johnboat, you can quietly puddle about in lily-pad pastures, dipping the bait in and out of holes. Since I live in a state where cane pole fishermen are rare, I don’t know all the fine points of this art. I did discover that if you tie too short a line on a limber cane pole, your catch bounces like a Yo-Yo just out of reach. A line three-fourths of the length of the pole is about right, with line of 6-to 8-pound test useful for general cane pole work.

You can use a cane pole for dapping by letting the wind carry the bait on very light line so that it repeatedly “kisses” the water. This can be killing over grass beds and for blasé fish.

Cane poles are the only really effective way to fish sunken brush tangles in streams. Using 10- or 12-pound-test line, and as much lead as needed to keep a straight line in the current, you can drop a cricket or katydid down to ferret out the fish. Again, cane poles are a godsend where tree branches grow very low to, or trail in, the water, since you can poke the bait back in behind them.

Warm, windy days knock many insect musicians off their stage and into an audience of hungry fish. Meadow streams which still hold trout are a rare find nowadays. They used to yield some of the summer’s best trout to a live or artificial hopper cast with the wind from tall grass banks. I usually make do with rock bass, smallmouth, and fall fish from such one-time trout streams as Beaver Creek, near Hagerstown, Maryland. It’s still enjoyable fishing, since the crowd is made up of cows and ducks, and instructive.

Pond panfish go on feeding sprees on windy days, too, though not always on the lee side. A 35 m.p.h. wind and I hit a long, skinny pond at the same time once. Much as I liked the sheltered side, the big bluegills and crappies didn’t. They were stationed in a sort of picket line about 10 yards out from the wind-beaten shore, presumably feeding on half-drowned insects which had drifted over. Crickets and grasshoppers fished just under the surface went like hotcakes for as long as I could take the buffeting.

A hot, still afternoon on a little stream can pose tough fishing, even with crickets and hoppers. You can always try the old trick of creating a food windfall by broadcasting baits sans hook. Or, you can go upstream and drop in bits of leaves, grass, and weeds. Raft a hopper down on a bit of flotsam, and make it hop off at the likeliest lunker lair. That little stunt has produced nice bass for me from creeks and drought-shrunk streams.

But I haven’t finished that September day on Unicorn Pond. When the bass switched off, I paddled the inflatable back to a broad shallows which fronted the ramp hole. With dusk coming, bullheads had begun to prowl. They gulped the remains of my cricket box, including those mashed by earlier fish. I added a delicious dozen 1- to 2-pounders to my stringer.

The singers of late summer had given their all, and had gone to glory. I left in the quiet of the evening, relaxed and refreshed, with a load of panfish taken in an old-fashioned way.